Introduction

The histories of the Jat and Sikh communities are interwoven threads in the rich tapestry of India’s past, marked by valor, faith, and an unwavering connection to the land. From the fertile plains of Punjab to the banks of the Ganga, these communities have shaped India through their martial prowess, spiritual resilience, and agrarian contributions. The Jats, a robust agrarian and warrior caste, and the Sikhs, born of Guru Nanak’s egalitarian vision, share a legacy that spans centuries of resistance, reform, and renewal.

Table of Contents

This article embarks on a journey through their histories, spotlighting iconic figures like Maharaja Ranjit Singh, Maharaja Surajmal, and Guru Gobind Singh, whose leadership defined epochs. It explores the rapid expansion (Rajay speed) of Ranjit Singh’s empire, Surajmal’s diplomatic genius, and Guru Gobind Singh’s transformation of Sikhs into a martial force. Beyond these luminaries, the narrative traces the spread of Jats along the Ganga, the coalitions between Jats and Sikhs, and the modern contributions of leaders like Chhotu Ram, Chaudhary Charan Singh, and Bhagat Singh. At its core, this story celebrates their enduring impact on farming communities and Indian society.

Why does this matter? In an era of rapid change, understanding the Jat-Sikh legacy offers insights into resilience, unity, and the power of grassroots movements. Let’s dive into their historical roots, their heroes, and their lasting influence.

Section 1: Historical Roots of Jats and Sikhs

The Jat and Sikh communities, though distinct in their historical trajectories, share a profound connection rooted in the soil of northwestern India. Their origins weave together tales of migration, martial valor, and spiritual evolution, forming a foundation that has sustained their resilience through centuries. This section delves into the ancient lineage of the Jats, the birth and growth of Sikhism, and the intriguing spiritual ties that link Jats to broader Indian traditions, offering a comprehensive look at their historical roots.

1.1 Origins of the Jat Community

The Jats, a people renowned for their rugged independence and agrarian prowess, trace their ancestry to a complex tapestry of nomadic tribes and settled farmers. Kalika Ranjan Qanungo’s History of Jats presents a compelling case for their origins among the Indo-Scythian tribes—pastoral warriors who migrated into India between the 2nd century BCE and the 4th century CE. These groups, including the Sakas and Kushans, swept through the northwestern frontier, eventually settling in the fertile plains of Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan. Over time, they blended with local populations, adopting agriculture while retaining their martial traditions.

Qanungo argues that the Jats’ ethnogenesis was not a singular event but a gradual fusion of cultures. Archaeological evidence, such as pottery and coinage from the Punjab region, supports this theory, suggesting a synthesis of Scythian mobility with indigenous agrarian practices. By the early medieval period, Jats had emerged as a distinct community, organized into clans like the Dahiyas, Sidhus, and Bhullars. Thakur Desh Raj’s Jat Itihas further details how these clans established self-sufficient villages, cultivating wheat, barley, and millet along the Indus and its tributaries.

The Jats’ dual identity as farmers and warriors crystallized during the Gupta Empire’s decline (circa 6th century CE), when regional instability demanded both tilling the land and defending it. Their resistance to centralized authority—be it Gupta, Rajput, or later Mughal—became a defining trait. For instance, in the 7th century, Jat chieftains in Multan repelled Arab incursions, a feat noted in early Islamic chronicles. This martial spirit, coupled with their agrarian roots, positioned them as a formidable force in northern India.

By the 11th century, Jat settlements dotted the landscape from Sindh to the Yamuna, their migrations driven by both opportunity and pressure from invaders like the Ghaznavids. Qanungo highlights their adaptability: in arid Rajasthan, they mastered pastoralism, while in Punjab’s lush plains, they pioneered irrigation systems using Persian wheels. This versatility laid the groundwork for their later expansion along the Ganga, a topic explored in Section 4. Their social structure, marked by egalitarianism and clan loyalty, further distinguished them from caste-bound neighbors, foreshadowing their receptivity to Sikhism’s inclusive ethos.

The Jats’ historical narrative is also one of cultural richness. Folk traditions, such as the Haryanvi Ragini songs, preserve tales of their early heroes—figures like Raja Shalivahan, a semi-legendary Jat king said to have defied foreign rulers. While these stories blend myth with history, they underscore the community’s pride in its ancient lineage, a pride that fueled their resilience through centuries of upheaval.

1.2 Birth of Sikhism and Its Foundations

Sikhism’s emergence in the late 15th century marked a radical departure from the religious landscape of medieval India, offering a path of equality and devotion that captivated the Jats. Khushwant Singh’s A History of Sikhs chronicles this birth under Guru Nanak (1469–1539), a visionary who rejected caste hierarchies and ritualistic excesses. Born in Talwandi (now Nankana Sahib, Pakistan), Nanak preached a monotheistic faith centered on Ik Onkar—one supreme reality—accessible to all through honest labor and remembrance of God. His message, delivered in simple Punjabi verse, found a ready audience among the Jats, whose egalitarian instincts aligned with his teachings.

Singh emphasizes that Sikhism’s early converts included many Jats disillusioned with Brahmanical dominance and the feudal oppression of Rajput landlords. Nanak’s travels across Punjab, Sindh, and beyond spread his gospel, establishing sangats (congregations) that transcended social divides. By his death in 1539, a nascent Sikh community had taken root, nurtured by successors like Guru Angad and Guru Amar Das, who codified the Gurmukhi script and expanded the faith’s organizational framework.

The turning point came with Guru Gobind Singh (1666–1708), the tenth Guru, whose leadership transformed Sikhism into a martial faith. Singh details how the Guru, facing relentless Mughal persecution, founded the Khalsa in 1699 at Anandpur. This baptized order, marked by the five Ks (Kesh, Kangha, Kara, Kirpan, Kachera), united Sikhs as a Sant-Sipahi (saint-soldier) community. The Khalsa’s creation was a direct response to the tyranny of Aurangzeb, whose policies—such as forced conversions and temple destruction—galvanized resistance.

Jats played a pivotal role in this transformation. Their martial heritage, honed through centuries of defending their lands, made them ideal recruits for the Khalsa. Singh notes that Jat Sikhs, including clans like the Sandhus and Manns, swelled the ranks, bringing their cavalry skills and fierce loyalty. The Battle of Bhangani (1688), where Guru Gobind Singh defeated hill rajas, showcased this synergy, with Jat warriors proving instrumental.

Sikhism’s foundations also rested on its agrarian ethos, a natural fit for Jat sensibilities. The langar (community kitchen), instituted by Nanak and expanded by his successors, mirrored the Jat tradition of collective labor during harvests. This institution not only fed the poor but also reinforced solidarity, a value Jats cherished in their clan-based society. By the 18th century, Sikhism had become a dominant force in Punjab, its growth intertwined with the Jat community’s ascent as a political and military power.

The faith’s appeal lay in its adaptability. While rooted in Punjab, it absorbed influences from Sufism and Bhakti traditions, broadening its reach. For Jats, Sikhism offered both spiritual liberation and a framework for resistance, setting the stage for leaders like Banda Bahadur and Maharaja Ranjit Singh to emerge from their ranks.

1.3 Jat Prachhun Buddh Hai: Spiritual Connections

Dharam Kirti’s Jat Prachhun Buddh Hai unveils a fascinating spiritual dimension of Jat history: their pre-Sikh ties to Buddhism. Before the rise of Sikhism or their widespread adoption of Hinduism, many Jat clans embraced Buddhist principles, a legacy rooted in the Mauryan era (3rd century BCE). Kirti argues that this connection shaped their worldview, predisposing them to egalitarian faiths like Sikhism.

Buddhism’s spread under Ashoka left a lasting imprint on northwestern India, with stupas and monasteries dotting the Punjab landscape. Jat tribes, as semi-nomadic settlers, likely encountered these teachings, adopting values of non-violence, community, and self-reliance. Kirti cites inscriptions from Sanchi and Taxila that mention pastoral groups—possibly proto-Jats—donating to Buddhist sanghas, suggesting a cultural exchange.

This Buddhist influence persisted subtly into the medieval period. The Jat aversion to priestly hierarchies and their emphasis on collective welfare echoed the Sangha’s democratic ethos. When Guru Nanak preached equality centuries later, Jats found a familiar resonance, easing their transition to Sikhism. Kirti posits that this spiritual continuity explains their rapid integration into the Khalsa, where Buddhist-inspired discipline merged with martial zeal.

Thakur Desh Raj complements this view, noting Jat folk tales that venerate figures like Siddhartha Gautama alongside local heroes. While not overtly Buddhist by the Mughal era, Jats retained a pragmatic spirituality—evident in their rejection of idolatry and preference for direct action—that bridged their ancient past with Sikh ideals. This synthesis enriched their identity, blending a warrior’s courage with a seeker’s introspection.

Section 2: Iconic Figures and Their Contributions

The Jat and Sikh legacies are illuminated by the towering figures who shaped their histories—leaders whose valor, vision, and resilience left an indelible mark on India. Maharaja Ranjit Singh, Maharaja Surajmal, and Guru Gobind Singh stand as exemplars of this heritage, each embodying distinct yet overlapping qualities: military genius, diplomatic acumen, and spiritual fervor. This section delves into their lives, contributions, and enduring influence, highlighting their roles in forging the Jat-Sikh identity and advancing their communities’ societal impact.

2.1 Maharaja Ranjit Singh: The Lion of Punjab

Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1780–1839), often dubbed the “Lion of Punjab,” was a colossus of Sikh history whose reign epitomized Rajay speed—the rapid and strategic expansion of his empire. Born into the Sukerchakia Misl, a Jat Sikh confederacy, Ranjit Singh inherited a modest chieftainship at age 12 amid the chaos following Mughal decline and Afghan invasions. His ascent, as chronicled in Khushwant Singh’s A History of Sikhs, transformed Punjab into a unified, secular state that rivaled contemporary powers.

Ranjit Singh’s rise began with the capture of Lahore in 1799, a bold move that established his capital and signaled his ambition. At just 19, he leveraged diplomacy and military might to consolidate the fractious Sikh Misls—12 independent chieftaincies—into a centralized monarchy. His Rajay speed was evident in his swift campaigns: by 1809, he secured the Sutlej River as his eastern boundary, negotiating with the British via the Treaty of Amritsar; by 1823, he annexed Multan and Kashmir, extending his dominion to the Khyber Pass. Singh notes that this expansion was no mere conquest but a calculated effort to secure Punjab’s borders against Afghan threats and British encroachment.

His military reforms were revolutionary. Ranjit Singh modernized the Khalsa Fauj (army), blending traditional Sikh cavalry with European artillery techniques. He recruited French and Italian officers—Jean-François Allard and Paolo Avitabile among them—to train his gunners, creating one of Asia’s most formidable forces. The Battle of Attock (1813), where his artillery overwhelmed Afghan defenses, showcased this prowess. Yet, his leadership transcended warfare: his secular administration employed Muslims like Fakir Azizuddin as foreign minister and Hindus like the Dogra brothers as generals, fostering a pluralistic state rare in its era.

For the Jat community, Ranjit Singh was a beacon of agrarian prosperity. Punjab’s economy thrived under his rule, with canals like the Shahpur Branch irrigating vast tracts of farmland. He reduced taxes on peasants, a policy that resonated with Jat values of hard work and fairness. His court in Lahore became a cultural hub, patronizing poets like Shah Mohammed and artisans who gilded the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple). The Nanakshahi rupee, his minted currency, symbolized economic independence, boosting trade along the Silk Route.

Ranjit Singh’s personal life reflected his charisma and complexity. Despite losing an eye to smallpox as a child, he exuded confidence, often leading battles himself. His diplomacy with the British—maintaining peace while fortifying his frontiers—demonstrated strategic foresight. His death in 1839, however, marked a turning point: internal rivalries and British opportunism dismantled his empire within a decade. Nevertheless, his legacy as a unifier endures, inspiring Jats and Sikhs as a model of leadership that balanced martial vigor with societal welfare.

His influence on Jat-Sikh coalitions was profound. By integrating Jat clans into his army and administration, he strengthened their bond with Sikhism, paving the way for their dominance in Punjab’s socio-political fabric. Today, Ranjit Singh remains a symbol of resilience, his name invoked in Punjabi folklore and Baisakhi celebrations as the ruler who made Punjab a golden land.

2.2 Maharaja Surajmal: The Jat Statesman

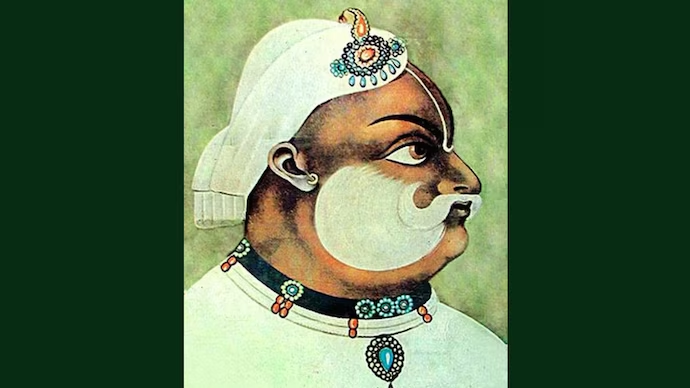

Maharaja Surajmal (1707–1763), the Jat ruler of Bharatpur, was a statesman whose reign elevated his people from a regional clan to a formidable power in 18th-century India. Natwar Singh’s Maharaja Surajmal portrays him as a master of both war and diplomacy, a leader who navigated the turbulent decline of Mughal authority with unparalleled skill. Born into the Sinsinwar Jat clan, Surajmal ascended to the throne in 1733, inheriting a small kingdom beset by rivals—Rajputs, Marathas, and Mughals alike.

Surajmal’s military achievements were anchored by the fortification of Bharatpur, a stronghold deemed impregnable. Constructed with mud walls reinforced by brick, it withstood multiple sieges, including a 14-week assault by the Marathas in 1754. His victory at the Battle of Maonda (1750) against Mughal forces under Safdarjung showcased Jat resilience, with Surajmal’s cavalry outmaneuvering a larger army. Thakur Desh Raj’s Jat Itihas credits his tactical brilliance to the Jat tradition of guerrilla warfare, honed over centuries of defending their lands.

Diplomacy, however, was Surajmal’s true genius. He forged alliances with the Rajputs of Jaipur and the Sikhs of Punjab, balancing power in a fragmented north India. His support for the Marathas at the Third Battle of Panipat (1761) against Ahmad Shah Abdali, though a strategic misstep due to the Maratha defeat, underscored his broader vision of resisting foreign domination. Natwar Singh highlights how Surajmal’s negotiations preserved Bharatpur’s autonomy, even as Mughal power waned and British influence grew.

Surajmal’s contributions extended beyond the battlefield. He transformed Bharatpur into an economic hub, promoting agriculture with irrigation projects along the Yamuna. His patronage of temples and forts—like Deeg and Lohagarh—reflected a commitment to Jat culture, blending martial pride with architectural splendor. Kalika Ranjan Qanungo notes that Surajmal’s reign marked the zenith of Jat political power, a period when their identity as a warrior-agrarian community crystallized.

His death in 1763, ambushed by Rohilla forces near Delhi, was a tragic loss. Bharatpur’s subsequent decline under weaker successors paved the way for British subjugation, but Surajmal’s legacy endured. For Jats, he remains a symbol of statesmanship and resistance, his name synonymous with Bharatpur’s golden age. His alliances with Sikhs laid early groundwork for later coalitions, reinforcing the Jat-Sikh bond against common foes.

Surajmal’s life also inspired Jat folklore, with ballads celebrating his courage and wisdom. His reign demonstrated how Jats could rise from humble origins to challenge empires, a narrative that resonates in their modern political assertiveness.

2.3 Guru Gobind Singh: The Warrior-Saint

Guru Gobind Singh (1666–1708), the tenth Sikh Guru, was a transformative figure whose creation of the Khalsa redefined Sikhism and galvanized the Jat community. Khushwant Singh’s A History of Sikhs describes him as a warrior-saint who fused spirituality with martial valor, forging a legacy that endures in Sikh and Jat identity. Born in Patna, he became Guru at age nine after his father Guru Tegh Bahadur’s martyrdom, inheriting a faith under siege by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb.

The founding of the Khalsa on Baisakhi 1699 at Anandpur was his defining act. Facing relentless persecution, Guru Gobind Singh baptized five Sikhs—the Panj Pyare—into a disciplined order, mandating the five Ks as symbols of commitment. This militarization turned Sikhs into a formidable force, with Jats forming its backbone. Singh notes that Jat recruits, like the Sidhus and Brars, brought their agrarian toughness and cavalry skills, amplifying the Khalsa’s strength.

His military campaigns were legendary. The Battle of Bhangani (1688) saw him defeat hill rajas, while the defense of Anandpur (1701–1704) against Mughal-Rajput coalitions tested his resolve. Despite losing his four sons to war and betrayal, his leadership never faltered. The escape from Chamkaur (1704), where he evaded capture with a handful of followers, became a tale of valor etched in Sikh lore.

Beyond warfare, Guru Gobind Singh was a prolific poet and scholar. His Dasam Granth—a collection of hymns and narratives—infused Sikhism with a martial spirit, while his declaration of the Guru Granth Sahib as eternal Guru ensured the faith’s continuity. His emphasis on equality and justice resonated with Jats, reinforcing their integration into Sikhism.

For Jats and Sikhs, his legacy is multifaceted: a spiritual guide who empowered the downtrodden, a warrior who defied tyranny, and a visionary who united diverse clans. His influence catalyzed Jat-Sikh coalitions, evident in later resistance movements under Banda Bahadur. Today, his name evokes reverence, his sacrifices celebrated in gurdwaras and Jat-Sikh households alike.

Section 3: Jat-Sikh Coalitions and Societal Impact

The Jat and Sikh communities, bound by shared geography, values, and struggles, have forged a dynamic partnership that has shaped India’s history. Their coalitions, rooted in resistance against oppression, evolved into a powerful socio-political force, influencing everything from military campaigns to agrarian reforms. This section explores the historical alliances between Jats and Sikhs, alongside the transformative contributions of modern leaders—Sir Chhotu Ram, Chaudhary Charan Singh, and Bhagat Singh—whose efforts uplifted their communities and left a lasting imprint on Indian society.

3.1 Historical Coalitions Between Jats and Sikhs

The Jat-Sikh alliance is a saga of solidarity forged in the crucible of adversity, stretching from the 18th century to the colonial era. Thakur Desh Raj’s Jat Itihas traces its origins to the post-Guru Gobind Singh period, when the Khalsa’s militarization drew heavily on Jat warriors. After the Guru’s death in 1708, Banda Bahadur, a Jat Sikh leader, emerged as a unifying figure. His guerrilla campaigns against Mughal rule (1710–1716) saw Jat clans from Punjab and Haryana join Sikh forces, attacking Mughal outposts like Sirhind and Samana. Khushwant Singh’s A History of Sikhs notes that Banda’s army, swelled by Jat peasants, embodied a shared ethos of defiance, blending Sikh discipline with Jat tenacity.

This coalition matured during the Sikh Misls era (1716–1799), a confederacy of 12 chieftaincies that dominated Punjab after Mughal decline. Jat Sikhs, such as those from the Phulkian and Sukerchakia Misls, played pivotal roles. The Bhangi Misl, led by Jat Sikh chieftains like Hari Singh, controlled Lahore, while the Kanaihya Misl, under Jai Singh, secured the Doaba region. These Misls, though often fractious, united against common foes—Afghan invaders like Ahmad Shah Abdali and Mughal remnants. The Battle of Lahore (1759), where Sikh-Jat forces repelled Abdali’s troops, showcased their combined might, liberating Punjab from foreign yoke.

Cultural ties deepened this alliance. Intermarriages between Jat and Sikh families became common, especially in rural Punjab, where clan networks transcended religious boundaries. Festivals like Baisakhi, originally a harvest celebration for Jats, evolved into a Sikh religious event post-Khalsa, symbolizing shared heritage. Thakur Desh Raj highlights how gurdwaras, built with Jat labor and resources, became communal hubs, reinforcing unity through langar and prayer.

The coalition faced its ultimate test during British rule. The First Anglo-Sikh War (1845–1846) saw Jat Sikhs like those from the Sandhu and Gill clans fight valiantly, though betrayal by Dogra generals led to defeat. The Revolt of 1857 further solidified this bond, as Jat and Sikh peasants in Punjab and Haryana defied British authority. Qanungo’s History of Jats cites instances of Jat villagers in Rohtak sheltering Sikh rebels, a testament to their enduring partnership.

This historical synergy had lasting effects. The Jat-Sikh alliance not only preserved their martial traditions but also fostered a collective identity that resisted assimilation. By the late 19th century, this unity underpinned their dominance in Punjab’s agrarian economy and military recruitment, setting the stage for modern leaders to emerge from their ranks.

3.2 Chhotu Ram and Chaudhary Charan Singh: Modern Reformers

The 20th century saw Jat-Sikh coalitions evolve into a force for social reform, spearheaded by Sir Chhotu Ram and Chaudhary Charan Singh—two titans whose advocacy reshaped rural India. Sir Chhotu Ram (1881–1945), a Jat leader from Haryana, emerged as a champion of farmers under British rule. Educated in law, he joined the Unionist Party in Punjab, a cross-communal alliance that prioritized agrarian interests. His tenure as Agriculture Minister (1924–1945) was transformative, as detailed in Jat Itihas.

Chhotu Ram’s flagship achievement was the Punjab Land Alienation Act (1901), which he strengthened to prevent moneylenders from seizing peasant land. He pushed for irrigation projects, like the Bhakra Dam’s early planning, ensuring water reached Jat and Sikh farmlands. His Punjab Restitution of Mortgaged Lands Act (1938) freed thousands of farmers from debt, earning him the title “Deenbandhu” (Friend of the Poor). For Sikh peasants in the canal colonies of Lyallpur (now Faisalabad), his policies meant economic stability, reinforcing Jat-Sikh solidarity in rural Punjab.

Chaudhary Charan Singh (1902–1987), a Jat from Uttar Pradesh, built on this legacy, rising to become India’s fifth Prime Minister (1979–1980). Born into a farming family in Noorpur, he joined the Indian National Congress, focusing on agrarian justice. His seminal work, India’s Poverty and Its Solution (1964), argued for smallholder empowerment, a cause rooted in Jat and Sikh traditions of self-reliance. As Uttar Pradesh’s Chief Minister (1967–1968), he enacted the UP Zamindari Abolition Act (1950), redistributing land to tenant farmers—many of them Jats and Sikhs in the western districts.

Charan Singh’s national impact came during the Green Revolution. As Union Agriculture Minister (1977), he promoted subsidies for fertilizers and irrigation, boosting wheat and rice yields in Punjab and Haryana. His policies empowered Jat-Sikh farmers, whose tractor-driven fields became India’s breadbasket. His brief premiership, though marred by political instability, cemented his image as a peasant leader, bridging Jat and Sikh agrarian interests across state lines.

Both leaders’ reforms had a profound societal impact. Chhotu Ram’s efforts curbed rural exploitation, while Charan Singh’s policies modernized agriculture, lifting millions from poverty. Their focus on education—Chhotu Ram founded schools in Rohtak, and Charan Singh supported rural colleges—empowered Jat-Sikh youth, fostering a politically conscious middle class. Their legacies endure in Haryana and Punjab’s robust farming communities, where their names are revered in village squares and political rallies.

3.3 Bhagat Singh: Revolutionary Inspiration

Bhagat Singh (1907–1931), though not a ruler or reformer in the traditional sense, embodied the Jat-Sikh spirit of rebellion, inspiring their communities to challenge colonial tyranny. Born into a Jat Sikh family in Lyallpur, Punjab, Bhagat Singh’s revolutionary zeal was ignited by the Jallianwala Bagh massacre (1919), which he witnessed as a boy. His short but electrifying life, as recounted in A History of Sikhs, fused Jat martial heritage with Sikh ideals of justice.

Bhagat Singh joined the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA), advocating armed resistance against British rule. His most daring acts—the bombing of the Central Legislative Assembly (1929) and the killing of J.P. Saunders in retaliation for Lala Lajpat Rai’s death—electrified India. Arrested and hanged at 23 in Lahore, his martyrdom galvanized the freedom struggle. Singh’s writings, like Why I Am an Atheist, revealed a sharp intellect, blending Marxist ideals with Jat-Sikh defiance.

For Jats and Sikhs, Bhagat Singh was a unifying icon. His family’s roots in the Sandhu clan tied him to Jat traditions, while his Sikh upbringing—marked by visits to gurdwaras—echoed Guru Gobind Singh’s call to resist oppression. His execution sparked protests across Punjab and Haryana, with Jat-Sikh youth joining revolutionary cells in droves. Qanungo notes that villages like Banga and Khatkar Kalan became hubs of anti-British sentiment, fueled by his legacy.

Bhagat Singh’s societal impact transcended his death. He inspired Jat-Sikh participation in the independence movement, bridging rural and urban struggles. Today, his image adorns Punjab’s streets, a reminder of the revolutionary fervor that continues to inspire their communities’ fight for justice.

Section 4: Spread of Jats and Sikh Influence

The Jat and Sikh communities, though rooted in the northwestern plains of India, extended their influence far beyond their origins, leaving a lasting imprint on the subcontinent’s landscape and culture. The Jats’ migration along the Ganga and the spread of Sikhism beyond Punjab represent a dynamic interplay of movement, adaptation, and resilience. This section examines the Jats’ eastward expansion and the diffusion of Sikh ideals, highlighting how these developments shaped agriculture, society, and identity across northern India.

4.1 Jat Expansion Along the Ganga

The Jats’ journey from their northwestern strongholds to the fertile plains of the Ganga is a testament to their adaptability and ambition. Kalika Ranjan Qanungo’s History of Jats traces this expansion to the early medieval period, when Jat clans began migrating from Punjab and Rajasthan toward the Doab region—the fertile corridor between the Yamuna and Ganga rivers. This movement, spanning the 9th to 16th centuries, was driven by a mix of push and pull factors: invasions from Central Asia, land scarcity in arid regions, and the promise of rich alluvial soil in the east.

Qanungo suggests that the Jats’ initial eastward shift coincided with the decline of the Gupta Empire (6th century CE), as weakened central authority allowed pastoral tribes to settle new territories. By the 11th century, Jat settlements dotted western Uttar Pradesh, with clans like the Tomars and Chauhans establishing villages in areas like Meerut and Bulandshahr. Thakur Desh Raj’s Jat Itihas details how these migrations intensified under the Delhi Sultanate (13th–16th centuries), as Jats fleeing Turko-Afghan raids sought refuge in the Gangetic plains. Their arrival transformed the region’s agrarian landscape.

The Jats brought with them a robust farming tradition, honed in Punjab’s semi-arid conditions. In the Doab, they introduced innovations like the Persian wheel—a water-lifting device that revolutionized irrigation. This technology, paired with their cultivation of hardy crops like millet and barley, turned marginal lands into productive fields. By the Mughal era (16th–18th centuries), Jat peasants had become a dominant force in the Gangetic economy, growing cash crops like sugarcane and cotton alongside staples like wheat. Qanungo cites Mughal revenue records that list Jat-dominated villages in Aligarh and Mathura as key contributors to imperial taxes, underscoring their agricultural prowess.

Their expansion wasn’t without conflict. The Jats’ martial heritage made them formidable adversaries to local rulers. In the 17th century, Jat rebellions against Mughal authority erupted across the Doab, led by figures like Gokula, who rallied peasants against Aurangzeb’s oppressive taxes in 1669. These uprisings, though suppressed, cemented the Jats’ reputation as a defiant community, paving the way for leaders like Maharaja Surajmal to later consolidate power in nearby Bharatpur. The Mughal chronicler Saqi Mustaid Khan noted the Jats’ “stubborn courage,” a trait that fueled their eastward push.

By the 18th century, Jat settlements stretched from Haryana to eastern Uttar Pradesh, with significant populations in districts like Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, and Bijnor. This eastward spread wasn’t merely geographic; it was cultural. Jat folk traditions—songs like Ragini and dances like Jhumar—blended with local customs, enriching the Gangetic cultural mosaic. Their clan-based social structure, emphasizing kinship and mutual aid, fostered tight-knit communities that resisted feudal exploitation, a legacy still evident in western UP’s Jat-dominated villages.

The British colonial period (19th–20th centuries) further amplified this expansion. The construction of the Upper Ganga Canal (1854) drew Jat farmers into canal colonies, boosting their agricultural output. Today, the Jat presence along the Ganga is a cornerstone of India’s agrarian economy, with their descendants thriving as landowners and cultivators in one of the world’s most fertile regions.

4.2 Sikh Influence Beyond Punjab

Sikhism, born in Punjab under Guru Nanak, transcended its regional origins to become a pan-Indian faith, with Jat converts playing a pivotal role in its spread. Khushwant Singh’s A History of Sikhs chronicles this diffusion, which began with Nanak’s travels (1490s–1520s) across India, from Assam to Tamil Nadu. His message of equality and devotion, delivered in vernacular hymns, resonated beyond Punjab, planting seeds that later flourished under his successors.

The militarization of Sikhism under Guru Gobind Singh (late 17th century) accelerated its outward reach. The Khalsa’s formation in 1699 attracted Jat warriors from Punjab and Haryana, many of whom carried Sikh ideals eastward as they migrated or served in Sikh armies. Singh notes that Banda Bahadur’s campaigns (1710–1716) against the Mughals spread Sikh influence into Haryana and western UP, with Jat Sikhs establishing sangats (congregations) in towns like Panipat and Rohtak. These early outposts laid the groundwork for Sikhism’s broader expansion.

The Sikh Misls era (1716–1799) further propelled this influence. As Misls like the Phulkian and Ahluwalia ventured beyond Punjab, they brought Sikhism to Rajasthan, Himachal Pradesh, and the Gangetic plains. Jat Sikhs, forming the bulk of these forces, settled in new territories, building gurdwaras that served as spiritual and social hubs. For instance, the gurdwara at Patiala, founded by Jat Sikh rulers in the 18th century, became a beacon for converts outside Punjab.

Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s empire (1799–1839) marked the zenith of Sikh influence. His conquests in Kashmir, Multan, and the northwest frontier spread Sikh governance and culture, while trade routes linked Punjab to the Gangetic plains. Jat Sikh traders and soldiers carried their faith to cities like Delhi and Lucknow, where gurdwaras like Sis Ganj and Rakab Ganj (built in the 18th–19th centuries) became centers of worship. Singh highlights how Ranjit Singh’s secular policies—employing Hindus and Muslims alongside Sikhs—broadened Sikhism’s appeal, attracting diverse adherents.

The British colonial era catalyzed further dissemination. The Sikh Regiment, recruited heavily from Jat Sikhs, served across India and abroad, introducing Sikh tenets to distant regions. The annexation of Punjab (1849) displaced many Sikhs, who migrated to canal colonies in Sindh and eastern UP, bringing their gurdwaras and langar traditions. By the early 20th century, Sikh communities thrived in cities like Kanpur and Varanasi, often led by Jat Sikh families who had adopted the faith generations earlier.

Sikhism’s influence wasn’t just geographic—it was cultural and social. The langar fostered community cohesion, appealing to Jat converts along the Ganga who valued collective welfare. Sikh emphasis on education, seen in institutions like Khalsa College (founded 1892 in Amritsar and replicated elsewhere), uplifted rural populations, including Jats in Haryana and UP. Singh notes that gurdwaras became rallying points during the freedom struggle, with Jat Sikhs like those in the Akali Movement (1920s) advocating for both religious reform and national liberation.

Today, Sikh influence extends globally, but its northern Indian spread—facilitated by Jat migrations—remains a cornerstone of its legacy. From Punjab to the Ganga, gurdwaras stand as testaments to this journey, their golden domes reflecting a faith that transcended borders through the resilience of its Jat-Sikh adherents.

Section 5: Modern Contributions to Farming and Society

The Jat and Sikh communities have transitioned from their historical roles as warriors and spiritual pioneers into modern architects of India’s agrarian and social landscape. Their contributions to farming and society in the 20th and 21st centuries reflect a blend of tradition and innovation, rooted in their deep connection to the land and commitment to collective welfare. This section examines their pivotal role in agricultural advancements and their significant socio-political influence, underscoring how these efforts have shaped modern India.

5.1 Jats and Sikhs in Agriculture

The Jat and Sikh communities have been the backbone of India’s agricultural revolution, transforming the nation from a food-scarce country into a global breadbasket. Their modern contributions, particularly during and after the Green Revolution (1960s–1970s), showcase their adaptability and industrious spirit. Kalika Ranjan Qanungo’s History of Jats emphasizes their historical aptitude for farming, a legacy that found new expression in the 20th century as they embraced technological advancements.

The Green Revolution, spearheaded by scientists like Norman Borlaug and Indian policymakers, introduced high-yield variety (HYV) seeds, chemical fertilizers, and mechanized farming. Jat and Sikh farmers in Punjab and Haryana were among the earliest adopters. Punjab, often called India’s “Granary,” owes its wheat and rice surpluses to their efforts. By the late 1960s, Jat Sikh farmers in districts like Ludhiana and Amritsar had tripled wheat yields, using HYV seeds like Kalyan Sona and irrigation from the Bhakra-Nangal Dam—a project championed by leaders like Chhotu Ram. Tractors, introduced en masse during this period, became a hallmark of their fields, with Punjab boasting the highest tractor density in India by the 1980s.

Haryana’s Jat farmers followed suit, turning the state into a rice and mustard powerhouse. The Upper Ganga Canal and tubewell irrigation, expanded under British rule and refined post-independence, enabled year-round cultivation. Qanungo notes that Jat ingenuity—seen in their medieval Persian wheel innovations—evolved into modern water management, with farmers digging deep borewells to tap groundwater. This resilience was critical during the 1965–1966 drought, when Punjab and Haryana’s output averted national famine.

Their contributions extended beyond productivity. Jat and Sikh farmers pioneered cooperative farming models, such as the Punjab Agricultural Cooperative Societies, established in the 1950s. These societies pooled resources for seeds, fertilizers, and machinery, ensuring smallholders—many of them Jats and Sikhs—could compete with larger estates. The kheti tradition, where families share labor during harvests, adapted to modern needs, fostering community resilience. By the 1970s, Punjab contributed over 60% of India’s wheat procurement, a feat driven by Jat-Sikh tenacity.

Post-Green Revolution, they faced challenges like soil degradation and water depletion, yet innovated further. The adoption of drip irrigation and organic farming in the 2000s reflects their forward-thinking approach. In Haryana, Jat farmers in Rohtak and Hisar shifted to horticulture—growing kinnow oranges and guavas—diversifying income streams. Sikh farmers in Punjab’s Malwa region experimented with zero-budget natural farming, reviving traditional methods like crop rotation to sustain soil health.

Their agricultural legacy has a broader societal impact. The prosperity generated fueled rural development—schools, roads, and hospitals sprouted in Jat-Sikh villages, funded by farming profits. Today, their fields remain a lifeline for India’s food security, with Punjab and Haryana producing over 20% of the nation’s wheat and rice, a testament to their enduring contribution to modern agriculture.

5.2 Socio-Political Influence

The Jat and Sikh communities have wielded significant socio-political influence in modern India, leveraging their agrarian strength into a powerful voice in governance and cultural preservation. Their journey from rural peasants to political powerhouses reflects a blend of grassroots activism and strategic leadership, as chronicled in Jat Itihas and A History of Sikhs. This influence spans local assemblies to national corridors, shaping policies and identities in the post-independence era.

The political ascent began with leaders like Chaudhary Charan Singh, whose premiership (1979–1980) epitomized Jat-Sikh advocacy for rural India. As a Jat from Uttar Pradesh, Charan Singh’s policies—subsidies for farmers, loan waivers, and land reforms—resonated with Jat and Sikh peasants in Punjab, Haryana, and western UP. His Lok Dal party, rooted in agrarian populism, drew massive support from these communities, cementing their electoral clout. In Punjab, Sikh leaders like Master Tara Singh and later Parkash Singh Badal of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) mirrored this influence, championing Sikh rights and farmers’ interests since the 1940s.

The Jat-Sikh political presence is stark in state legislatures. Haryana’s assembly has long been dominated by Jat leaders—Bansi Lal, Devi Lal, and Om Prakash Chautala—who prioritized irrigation and rural electrification. Punjab’s politics, shaped by SAD and Congress, reflects Sikh leadership, with Jat Sikhs forming a majority of its rural electorate. The 1966 Punjab Reorganization Act, creating Haryana and modern Punjab, was partly a response to Jat-Sikh demands for regional autonomy, a legacy of their historical coalitions.

Their socio-political activism peaked during the farmers’ protests (2020–2021) against India’s farm laws. Jat and Sikh farmers from Punjab and Haryana led a year-long agitation at Delhi’s borders, using tractors as symbols of resistance. The movement, rooted in their tradition of collective action, forced the government to repeal the laws, showcasing their ability to influence national policy. Singh notes that gurdwaras played a key role, providing langar to protesters, blending Sikh service with Jat defiance.

Culturally, Jats and Sikhs have preserved their identity amidst modernization. Baisakhi, once a harvest festival, remains a vibrant celebration of Jat-Sikh heritage, with bhangra and gidda dances echoing their rural roots. Gurdwaras and Jat community centers host literacy drives and health camps, sustaining the langar ethos of equality. The Punjabi language, championed by Sikh scholars and Jat poets like Waris Shah, thrives as a cultural unifier, with Jat-Sikh diaspora in Canada and the UK amplifying its global reach.

Their influence extends to education and social reform. The Khalsa College in Amritsar, founded in 1892, and Chaudhary Charan Singh University in Meerut, established in 1965, reflect their commitment to learning, producing generations of Jat-Sikh professionals. Social movements like the Kisan Sabha, led by Jat-Sikh activists in the 1930s, tackled rural debt and tenancy issues, laying groundwork for modern cooperative societies.

Challenges remain—caste tensions among Jats and political factionalism among Sikhs occasionally fracture their unity. Yet, their socio-political influence endures, evident in their representation in India’s armed forces, bureaucracy, and parliament. From village panchayats to the Lok Sabha, Jats and Sikhs continue to shape India’s democratic fabric, their voices a powerful echo of their agrarian and martial past.

Conclusion

The Jat-Sikh legacy is a saga of resilience, from ancient migrations to modern reforms. Figures like Ranjit Singh, Surajmal, and Guru Gobind Singh laid foundations of valor and faith, while Chhotu Ram, Charan Singh, and Bhagat Singh carried their spirit into the 20th century. Their contributions to farming and society remain vital to India’s story. As we reflect on their odyssey, we’re reminded of the power of unity and perseverance—values worth cherishing today.

References

- Singh, Khushwant. A History of Sikhs. Oxford University Press.

- Qanungo, Kalika Ranjan. History of Jats. Originals Publishing.

- Kirti, Dharam. Jat Prachhun Buddh Hai. Sikh Publishing House.

- Raj, Thakur Desh. Jat Itihas. Rajkamal Prakashan.

- Singh, Natwar. Maharaja Surajmal. Rupa Publications.