Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi (c. 1942 – October 20, 2011) was a polarizing figure whose 42-year rule over Libya left an indelible mark on the nation and the world. Rising from humble Bedouin origins to become a revolutionary leader, Gaddafi’s life was a complex blend of idealism, authoritarianism, and controversy. His policies transformed Libya, particularly for the poor, whom he claimed to champion, yet his repressive tactics and international entanglements led to his brutal demise during the Arab Spring. This article explores Gaddafi’s life in depth, drawing on verified sources, historical records, and evidence to provide a comprehensive, original account, with a special focus on his thoughts and policies toward the poor.

Table of Contents

Early Life: A Bedouin Childhood Under Colonial Rule

Muammar Gaddafi was born around 1942 in a tent near Qasr Abu Hadi, a desert village outside Sirte in Tripolitania, then an Italian colony. The exact date is uncertain, as Bedouin families rarely kept written records (Britannica, 2025). He was the youngest of four children and the only son of Aisha bin Niran and Mohammad Abdul Salam bin Hamed, members of the Qadhadhfa tribe, a minor Arab Bedouin group that sustained itself through nomadic herding (Vandewalle, 2012, p. 26). Living in poverty, the family faced the harsh realities of desert life, moving frequently to find grazing land for their camels and goats. This upbringing instilled in Gaddafi a deep connection to Bedouin culture and a resentment of foreign domination, which would shape his lifelong ideology.

Libya’s colonial history profoundly influenced Gaddafi’s early years. Italy had controlled Libya since 1911, and the brutal suppression of resistance, including the use of concentration camps and chemical weapons, was part of the collective memory of his tribe (Ahmida, 2005, p. 45). His paternal grandfather was killed during the Italian invasion, a family tragedy that Gaddafi later cited as a driving force behind his anti-colonialism (BBC News, 2011a). After Italy’s defeat in World War II, Libya came under British and French administration, further exposing young Muammar to the inequities of foreign rule.

Education was a rare privilege for Bedouin children, but Gaddafi’s father, though illiterate, valued learning and enrolled Muammar in a primary school in Sirte. Demonstrating remarkable diligence, Gaddafi completed six grades in four years, sleeping on a mosque floor during the week to save money and walking 20 miles home on weekends (Vandewalle, 2012, p. 27). As a Bedouin in an urban school, he faced bullying from city-dwelling classmates, which deepened his sense of marginalization and reinforced his tribal pride (Britannica, 2025).

In 1956, the family relocated to Sabha in Fezzan, where Gaddafi’s father worked as a caretaker. Muammar attended secondary school, a significant achievement for someone of his background (BBC News, 2011a). At Sabha, he encountered Egyptian teachers who introduced him to the revolutionary ideas of Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s president and a proponent of pan-Arabism. Nasser’s calls for Arab unity and independence resonated with Gaddafi, who began organizing student discussions on anti-colonialism. In 1961, he was expelled from school for leading a protest against Syria’s secession from the United Arab Republic, marking his emergence as a political activist (Vandewalle, 2012, p. 28).

Military Training and Revolutionary Ambitions

Determined to challenge Libya’s pro-Western monarchy under King Idris I, Gaddafi enrolled in the University of Libya in Tripoli in 1963, earning a history degree that deepened his understanding of Libya’s colonial past (Britannica, 2025). That same year, he entered the Royal Military Academy in Benghazi, where he recruited like-minded cadets to form the Central Committee of the Free Officers Movement, a secretive group modeled after Nasser’s 1952 Egyptian coup (Vandewalle, 2012, p. 30). Gaddafi’s charisma and organizational skills made him the group’s leader.

In 1966, Gaddafi was sent to the United Kingdom for military training, attending courses in Beaconsfield, Bovington Camp, and Hythe. He excelled in military signaling and learned English, earning praise for his discipline (The Guardian, 2011a). However, he felt alienated, claiming British officers racially insulted him. To assert his Arab identity, he walked through London’s Piccadilly in traditional Libyan robes, a defiant act of cultural pride (BBC News, 2011a). This experience solidified his rejection of Western influence.

Returning to Libya in 1966 as a commissioned officer in the Signal Corps, Gaddafi expanded his revolutionary network. King Idris’s regime was deeply unpopular, marred by corruption and reliance on Western powers, which maintained military bases in Libya (Ahmida, 2005, p. 67). By 1969, Gaddafi and his Free Officers were ready to act. On September 1, 1969, while Idris was in Turkey, Gaddafi led a bloodless coup, seizing key institutions and deposing the monarchy (Vandewalle, 2012, p. 35). At 27, he declared himself chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC) and commander-in-chief, adopting the rank of colonel in homage to Nasser (Britannica, 2025).

Rise to Power: Rebuilding a Nation

Gaddafi’s early rule focused on dismantling Libya’s colonial legacy and redistributing wealth. Inspired by Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal, he targeted Libya’s oil industry, controlled by foreign companies like Esso and Shell. He renegotiated contracts to favor Libya, nationalized oil production, and expelled Italian and Jewish residents, seizing their assets (Vandewalle, 2012, p. 40). These moves increased oil revenues from $1.4 billion in 1969 to $13.3 billion by 1980, earning Gaddafi widespread support as a champion of national sovereignty (Pargeter, 2012, p. 55).

The RCC, under Gaddafi’s leadership, adopted the motto “Unity, Freedom, Socialism” and established the Libyan Arab Republic. Gaddafi introduced social welfare programs, making education and healthcare free and compulsory. He launched the Great Man-Made River project, a $25 billion irrigation system to bring water to coastal cities, reflecting his commitment to development (Pargeter, 2012, p. 60). These initiatives aimed to improve the lives of ordinary Libyans, particularly the poor, whom Gaddafi viewed as the nation’s backbone.

Gaddafi’s Bedouin roots shaped his empathy for the disadvantaged. In speeches, he recalled his impoverished childhood, positioning himself as a “simple revolutionary” dedicated to the masses (The Guardian, 2011a). Policies like subsidized housing and wage increases addressed economic disparities. By the 1980s, Libya’s per capita income reached over $11,000, among Africa’s highest, and literacy rates rose from 10–25% to over 93% (Vandewalle, 2012, p. 45; Pargeter, 2012, p. 62).

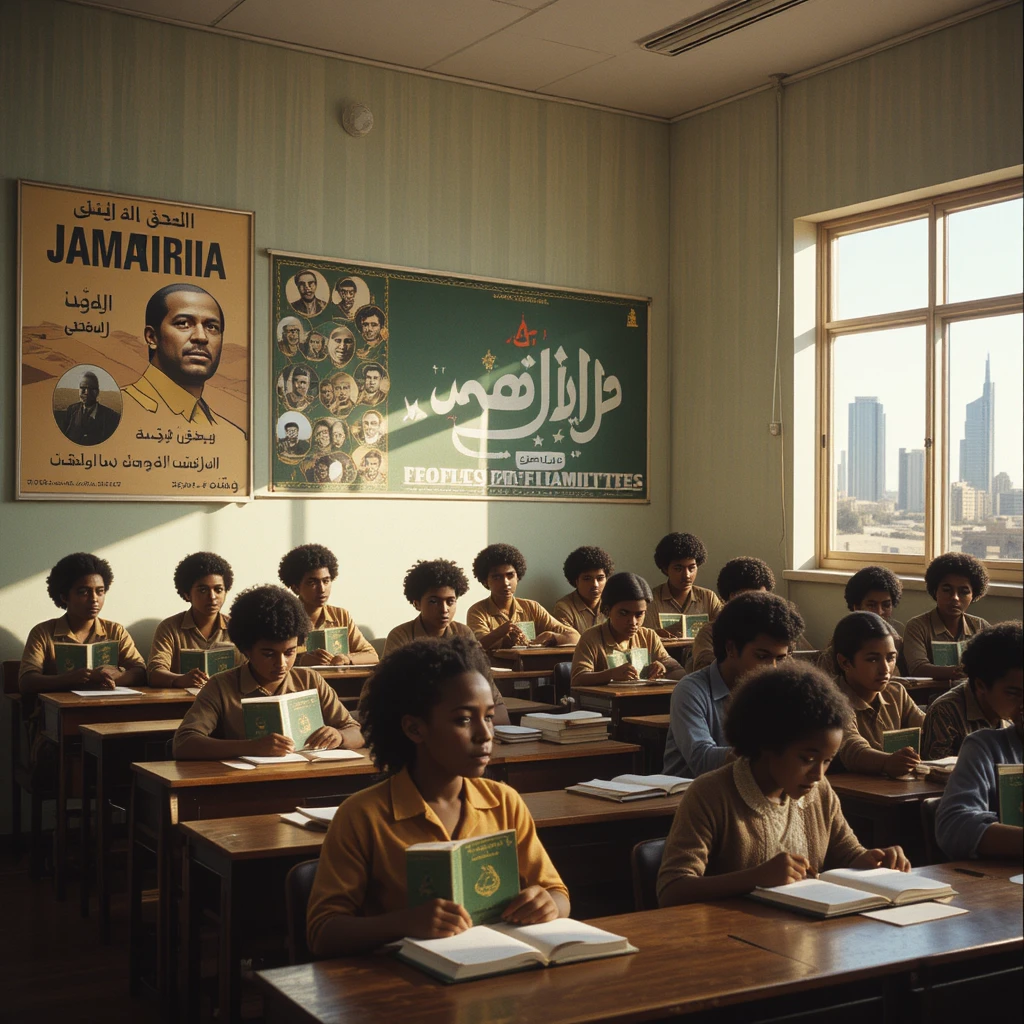

The Green Book and the Jamahiriya Vision

By the mid-1970s, Gaddafi sought to formalize his political philosophy. Disillusioned with capitalism and communism, he developed the “Third International Theory,” outlined in his three-volume Green Book (1975–1979). The Green Bookrejected parliamentary democracy as a “dictatorship” of the majority party and proposed the Jamahiriya—a “state of the masses”—where power would flow through people’s committees and popular congresses (Gaddafi, 1975, p. 15).

In 1977, Gaddafi abolished the Libyan Arab Republic and declared the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. He stepped down from formal roles, adopting the title “Brotherly Leader and Guide of the Revolution” (Vandewalle, 2012, p. 50). In theory, the Jamahiriya empowered citizens. In practice, Gaddafi retained absolute control, using revolutionary committees and security forces to suppress dissent (Pargeter, 2012, p. 70). The Green Book became mandatory in schools, shaping Libya’s policies.

The Green Book emphasized equitable wealth distribution, reflecting Gaddafi’s focus on the poor. He viewed private enterprise as exploitative, leading to a 1980s ban on private businesses and a “cultural revolution” that included burning “unsound” books (Vandewalle, 2012, p. 55). These policies caused economic stagnation and shortages, undermining his goals (Pargeter, 2012, p. 75).

Gaddafi’s connection to the poor was personal. He retreated to the desert to meditate, shunning ostentatious wealth and preferring military uniforms or traditional robes (BBC News, 2011b). However, Western sanctions and mismanagement hindered progress, and some Libyans felt he squandered oil wealth on foreign ventures (Human Rights Watch, 2012).

International Ambitions and Controversies

Gaddafi’s anti-imperialist stance made him a global figure. He supported liberation movements, including Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress and Yasser Arafat’s Palestine Liberation Organization (Vandewalle, 2012, p. 80). His Islamic Legion promoted Arabization in Africa but was criticized for brutality (Pargeter, 2012, p. 85). His alleged support for terrorism, including the 1986 West Berlin discotheque bombing and the 1988 Lockerbie bombing, which killed 270 people, earned him Western enmity (BBC News, 2011a). U.S. President Ronald Reagan called him the “mad dog of the Middle East” (The Guardian, 2011a).

The U.S. retaliated with 1986 airstrikes on Tripoli, targeting Gaddafi’s residence and killing his infant daughter, Hana (Human Rights Watch, 2012). These events deepened Gaddafi’s paranoia and belief in a Western-Zionist conspiracy. His international vision included pan-African unity and a gold-backed African currency, which alarmed Western powers (Vandewalle, 2012, p. 90).

Personal Life and Public Persona

Gaddafi was private yet flamboyant. Described by his father as “serious” and pious, he was shaped by his Bedouin upbringing, traveling with a tent and insisting on camel milk (BBC News, 2011b). He saw himself as a fashion icon, claiming, “Whatever I wear becomes a fad,” with his colorful robes drawing attention (The Guardian, 2011a).

Gaddafi married twice. His first marriage to Fatiha al-Nuri produced one son, Muhammad, but ended in 1970. His second wife, Safia Farkash, bore seven children—Saif al-Islam, Al-Saadi, Mutassim, Hannibal, Ayesha, Saif al-Arab, and Khamis—and two adopted children, Hana and Milad (Vandewalle, 2012, p. 95). His sons’ lavish behavior fueled resentment.

A devout Muslim, Gaddafi interrupted meetings to pray and saw his rule as a divine mission (Pargeter, 2012, p. 100). His idiosyncratic Islam blended Salafist elements with calls for Sunni-Shia unity. Some suggest he had narcissistic tendencies, evidenced by titles like “King of Kings of Africa” (The Guardian, 2011a).

Thoughts and Feelings About the Poor

Gaddafi’s commitment to the poor was rooted in his childhood poverty and socialist ideology. He viewed the “masses” as Libya’s true owners, arguing oil wealth should serve the people (Gaddafi, 1975, p. 20). In a 1973 speech, he said, “Libya lived for 5,000 years without oil and is ready to live another 5,000 years without it,” emphasizing self-reliance (The Guardian, 2011a).

His policies—free education, healthcare, subsidized housing, and the Great Man-Made River—aimed to uplift the disadvantaged (Vandewalle, 2012, p. 60). He saw the Bedouin as Libya’s moral core, contrasting their simplicity with urban corruption. The Green Book advocated for a system where the poor governed themselves (Gaddafi, 1975, p. 25).

However, Gaddafi’s paternalism led him to believe he alone could guide the masses, justifying authoritarianism. His paranoia caused him to distrust even those he championed, fearing foreign exploitation (Pargeter, 2012, p. 105). While he improved living standards, economic mismanagement and repression alienated many (Human Rights Watch, 2012).

The Arab Spring and Downfall

The Arab Spring of 2011, sparked by uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt, ignited protests in Benghazi. Repression, economic stagnation, and resentment over his sons’ behavior fueled unrest (BBC News, 2011a). Gaddafi responded with force, calling opponents “cockroaches” and “rats” (The Guardian, 2011b). His crackdown prompted international outrage.

NATO, authorized by UN Resolution 1973, launched airstrikes to protect civilians, but the intervention aimed at regime change (Human Rights Watch, 2012). Gaddafi fled Tripoli in August 2011, hiding in Sirte. On October 20, 2011, his convoy was struck by a NATO missile. Wounded, Gaddafi hid in a drainage pipe, where Misrata-based militias captured him, beating and wounding him (Reuters, 2011). Videos show him pleading, “What did I do to you?” before he was shot (The Guardian, 2011b). His son Mutassim was also executed. Gaddafi’s body was displayed in a Misrata freezer (BBC News, 2011a).

Evidence suggests Gaddafi was executed, violating international law (Human Rights Watch, 2012). Some argue NATO’s intervention was driven by Gaddafi’s African currency plans (Vandewalle, 2012, p. 100).

Legacy and Reflections

Gaddafi’s legacy is divisive. Supporters credit him with free education, healthcare, and oil wealth distribution (Pargeter, 2012, p. 110). Critics condemn his repression and mismanagement, which led to post-2011 chaos (Human Rights Watch, 2012). His commitment to the poor was genuine but undermined by authoritarianism.

Gaddafi’s final plea—“What did I do to you?”—revealed the gap between his self-image and public rage (The Guardian, 2011b). His life is a cautionary tale of revolutionary zeal unchecked by accountability.

References:

- Ahmida, A. A. (2005). Forgotten Voices: Power and Agency in Colonial and Postcolonial Libya. Routledge.

- BBC News. (2011a). “The Muammar Gaddafi story.” October 21, 2011. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-15390907

- BBC News. (2011b). “Gaddafi’s quixotic and brutal rule.” October 20, 2011. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-15389550

- Britannica. (2025). “Muammar al-Qaddafi.” June 18, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Muammar-al-Qaddafi

- Gaddafi, M. (1975). The Green Book: Part One. Public Establishment for Publishing.

- Human Rights Watch. (2012). “Death of a Dictator: Bloody Vengeance in Sirte.” October 17, 2012. https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/10/17/death-dictator/bloody-vengeance-sirte

- Pargeter, A. (2012). Libya: The Rise and Fall of Qaddafi. Yale University Press.

- Reuters. (2011). “Gaddafi caught like ‘rat’ in a drain.” October 21, 2011. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-libya-gaddafi-finalhours-idUSTRE79K1DA20111021

- The Guardian. (2011a). “Muammar Gaddafi: The early years.” October 20, 2011. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/oct/20/muammar-gaddafi-obituary

- The Guardian. (2011b). “Gaddafi’s last words.” October 23, 2011. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/oct/23/gaddafi-last-words-plea-spare

- Vandewalle, D. (2012). A History of Modern Libya. Cambridge University Press.