Ancient Beginnings: Jat Origins in the Indus Valley (Pre-5th Century AD)

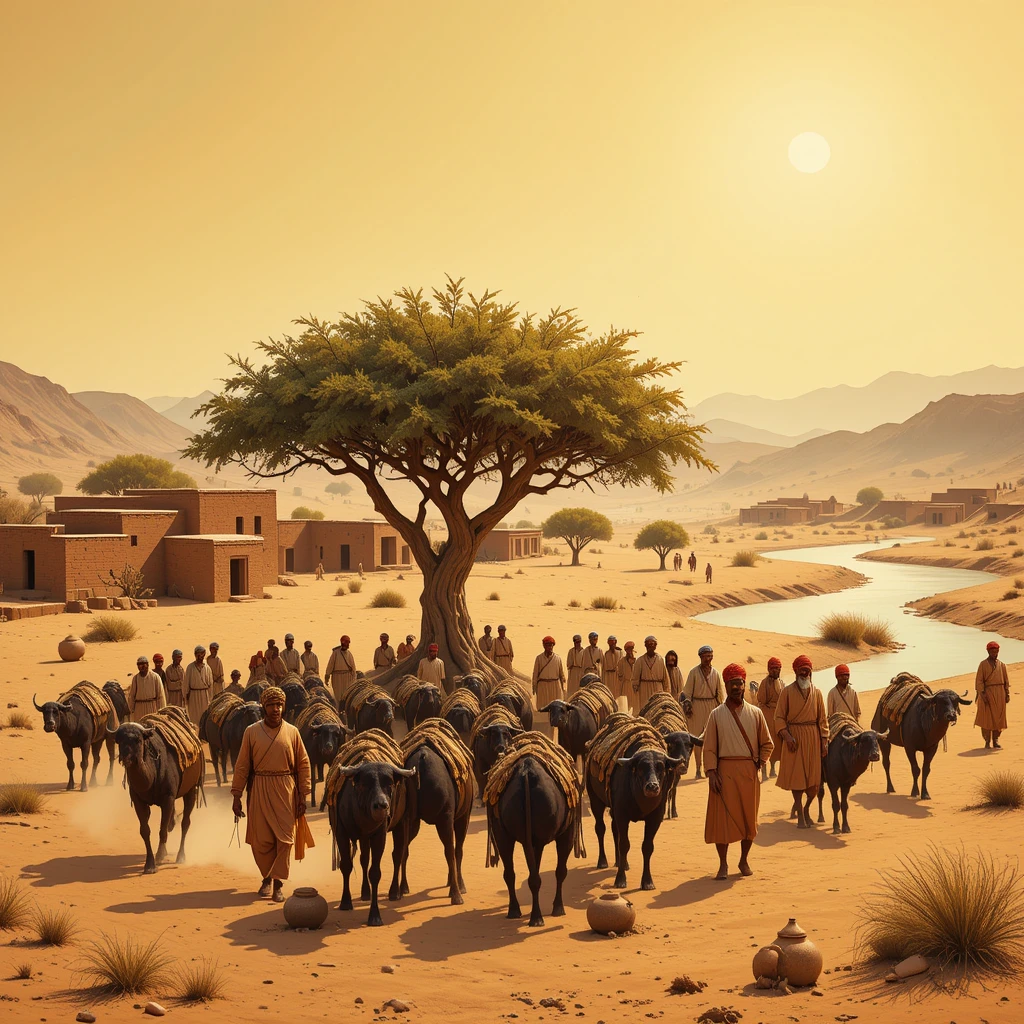

The Zutt Rebellion, a significant yet understudied uprising in early Islamic history, traces its roots to the ancient Indus Valley, where the Jat people—also known as Jatts or Jutts—developed a distinct identity as pastoralist tribes. Inhabiting the arid plains of modern-day Sindh, Punjab, and Rajasthan (Pakistan and India), they herded cattle, buffaloes, and camels, adapting to harsh environments through advanced irrigation and animal husbandry. Archaeological evidence from Indus Valley Civilization sites like Mohenjo-Daro (circa 2600–1900 BC) suggests proto-Jat communities, though direct connections remain speculative due to sparse records.

Table of Contents

Ancient texts offer clues. The Rigveda (circa 1500–1200 BC) mentions pastoral tribes outside the Vedic order, potentially Jat ancestors, valued for resilience but marginalized as non-Vedic. The Mahabharata (circa 400 BC–400 AD) references warrior-herders like the Yaudheyas, linked by historians to early Jat clans for their defiance against centralized powers. The Puranas (300–1000 AD), preserved in Sanskrit manuscripts at the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, classify such groups as Shudras, reflecting Brahmanical biases against their pastoral lifestyle. [25][28][31]

Jat society was organized into gotras (clans) like Sandhu and Khokhar, fostering unity through kinship and panchayats(village councils). Environmental challenges—famines and floods—and invasions by Scythians (circa 100 BC) and Kushans (1st–3rd centuries AD) tested their adaptability. Herodotus (5th century BC) described nomadic tribes like the Massagetae, whose warrior ethos aligns with Jat characteristics, supported by genetic studies linking them to Indo-Aryan migrations. Jat folklore, recorded in H.A. Rose’s The Tribes and Castes of the Punjab (1911), claims descent from Lord Shiva, symbolizing martial pride. These early dynamics prepared Jats for migrations driven by necessity and opportunity. [29][30][52]

Sasanian Era: Westward Migration and Mesopotamian Integration (5th–7th Centuries AD)

The 5th century AD marked a turning point as Jat groups, termed “Zutts” in Persian records (from the Arabicized “Jat”), were resettled by the Sasanian Empire (224–651 AD). Emperor Bahram V (r. 420–438 AD) relocated them from Sindh to southern Mesopotamia to enhance agriculture. Fleeing famines or captured in raids, Zutts introduced buffalo herding and rice cultivation, digging canals like the Nahr al-Zuṭṭ, transforming the Tigris-Euphrates marshes. Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh (1010 AD), preserved in British Library manuscripts, indirectly references these “Indian” settlers as laborers and border guards. [0][2][42]

By Yazdegerd III’s reign (r. 632–651 AD), Zutts served as cavalry, fighting at al-Qadisiyyah (636 AD) but defecting to Muslim forces, ensuring survival. In Iraq, they intermarried with Arabs, forming the Banu Zutt tribe, blending Indo-Aryan traditions with local customs. Al-Baladhuri’s Futuh al-Buldan (9th century), held in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, details their irrigation and textile contributions, including “zuttī” cloth. Despite cultural retention—music, attire—they faced marginalization, labeled “black” alongside Zanj in Arabic texts, foreshadowing tensions. [44][45][47] Their marsh navigation skills, rooted in Indus experience, later fueled rebellion. [49]

Rashidun and Umayyad Periods: Conquest and Dispersal (7th–8th Centuries AD)

The Islamic conquests reshaped Zutt trajectories. During the Rashidun Caliphate (632–661 AD), Arab armies under Umar ibn al-Khattab met Jat resistance at Ahwaz (640 AD). Post-surrender, Zutts were resettled in Basra and Kufa as guards. The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 AD) intensified dispersal after Muhammad bin Qasim’s 712 AD conquest of Sindh, chronicled in the Chach Nama (13th-century Persian translation, British Library). Jats resisted at Aror with King Dahir but were defeated, with thousands transported to Iraq, Syria, and Antioch as captives or auxiliaries. [3][5][63]

Ibn Khordadbeh’s Kitab al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik (9th century, Bodleian Library) describes Zutts as pastoralists and archers in “bilād al-Zāt.” Allied with Banu Tamim, they faced heavy taxes and demilitarization under al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, breeding resentment. Their control of marsh waterways positioned them for revolt. [11][27]

Abbasid Era: Prosperity and Prelude to Rebellion (8th–Early 9th Centuries AD)

The Abbasid Revolution (750 AD) promised equity, but Zutts faced persistent exclusion. Under al-Mansur (r. 754–775 AD) and Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809 AD), they supported irrigation and military efforts, yet endured restrictive policies. The Fourth Fitna (809–813 AD), a civil war between al-Amin and al-Ma’mun, weakened Abbasid control, allowing Zutts to levy tolls and raid caravans. Al-Tabari’s Tarikh al-Rusul wa al-Muluk (9th–10th centuries, Leiden edition) notes their growing assertiveness in the marshes. [0][32][45]

The Jatts or Jutts or Zutt Rebellion: Outbreak and Early Successes (810–820 AD)

Around 810 AD, Yusuf ibn Zutt rallied marsh tribes, declaring semi-autonomy and disrupting Baghdad’s supply lines. With up to 50,000 fighters, Zutts used boats and reed cover for ambushes, leveraging Indus-honed guerrilla tactics. Al-Ma’mun’s campaigns, led by Isa ibn Yazid al-Juludi (814 AD) and Ahmad ibn Qutayba (816 AD), failed against marsh terrain, with generals like Al-Jarrah ibn ‘Abdallah killed. By 820 AD, Muhammad ibn Uthman took leadership, expanding to Kufa and Al-Jazira, forming a de facto state. [1][2][39][40]

Peak of Power: Territorial Gains and Economic Impact (821–833 AD)

The 820s saw Zutt dominance. In 822 AD, they captured Basra via waterway sieges, followed by Wasit in 824 AD. Raids reached Al-Jazira by 825 AD, disrupting grain supplies to Baghdad. Al-Ya’qubi’s Tarikh (9th century) records economic strain, with market shortages. Al-Ma’mun’s counteroffensives, including Abdallah ibn Mu’awiya’s in 828 AD, faltered, with generals lost to ambushes. Zutt tactics—palm grove hideouts, buffalo transport—paralyzed Abbasid logistics. [0][45][46]

Defeat and Dispersal: Abbasid Victory (833–835 AD)

Al-Mu’tasim’s ascension in 833 AD brought reform. In 834 AD, Ujayf ibn Anbasa led 10,000 troops to Wasit, using canal blockades and sieges. After nine months of heavy casualties, Zutts surrendered in 835 AD under Muhammad ibn Uthman. Al-Mu’tasim deported thousands to Cilicia, Bahrain, and Khuzestan, fragmenting their communities. Al-Tabari details this dispersal, noting some joined the Zanj Rebellion (869–883 AD). By the 11th century, Zutt identity faded in chronicles through assimilation. [1][2][44][51]

Medieval Transformations: Jat Evolution in South Asia (9th–16th Centuries AD)

In the Indus Valley, Jats migrated to Punjab, adopting agriculture with the Persian wheel. Under the Delhi Sultanate and Mughals, clans like Bhattis rose. Sufi-led conversions to Islam (13th–16th centuries) and Sikhism under Guru Nanak diversified them. Rebellions, like Gokula’s (1669 AD), echoed Zutt defiance. Abu’l-Fazl’s Ain-i-Akbari (16th century, Asiatic Society, Kolkata) documents Jat contributions. [8][36][63]

Modern Jats: Legacy and Continuity (17th Century–Present)

Today, 33 million Jats span India and Pakistan, with 47% Hindu, 33% Muslim, and 20% Sikh. As agriculturists and political figures (e.g., Charan Singh, Hina Rabbani Khar), they shape regional dynamics. Cultural traditions—Punjabi music, clan endogamy—persist, though urbanization challenges rural roots. Genetic studies (American Journal of Human Genetics, 2018) link Jats to Indo-Aryans, with Marsh Arab DNA suggesting Zutt ancestry. Social media reflects pride, with humorous claims of figures like Saddam Hussein as Jat, though unsupported. [4][21][23][24]

Conclusion

The Zutt Rebellion reflects a people’s resilience against displacement and oppression, from Indus pastoralists to Mesopotamian rebels and modern agrarian leaders. Ancient manuscripts and modern scholarship illuminate their enduring legacy across centuries and continents.

Primary Sources and Manuscripts

- Tarikh al-Rusul wa al-Muluk by al-Tabari (839–923 AD): Leiden University Library; rebellion details.

- Futuh al-Buldan by al-Baladhuri (d. 892 AD): Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; Zutt migrations.

- Chach Nama (13th-century Persian, 8th-century Arabic): British Library; Sindh conquest.

- Kitab al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik by Ibn Khordadbeh (d. 912 AD): Bodleian Library, Oxford; Zutt roles.

- Tarikh by al-Ya’qubi (d. 897 AD): Manuscript editions; economic impacts.

- Ain-i-Akbari by Abu’l-Fazl (16th century): Asiatic Society, Kolkata; Jat contributions.

Modern Books

- History of the Jats by Kalika Ranjan Qanungo (1925, revised 1954): Jat evolution in India.

- The Jats: Their Origin, Antiquity and Migrations by Yashpal Gulia (1992): Ancient roots.

- The Tribes and Castes of the Punjab by H.A. Rose (1911): Jat culture.

- Jats and Gujars by Rahit Vashist (1973): Clan structures.

References

[0] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zu%E1%B9%AD%E1%B9%AD

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zutt_Rebellion

[2] https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Zutt_Rebellion

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jats

[5] https://countercurrents.org/2021/01/jats-a-brief-history/

[8] https://www.jatland.com/home/Life%2C_culture_and_traditions_of_Jat_people

[11] https://jatchiefs.com/history/

[21] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002929718303987

[23] https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/jats

[24] https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/jats-in-india-history-lifestyle-statewise-jats-numbers-in-india-9080587/

[25] https://ijassonline.in/HTML_Papers/International%2520Journal%2520of%2520Advances%2520in%2520Social%2520Sciences__PID__2017-5-4-8.html

[26] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zu%E1%B9%AD%E1%B9%AD

[27] https://www.reddit.com/r/punjabi/comments/12f3gts/did_jutt_people_have_contacts_with_the_arab/

[28] https://anvpublication.org/Journals/HTMLPaper.aspx?Journal=International%2BJournal%2Bof%2BAdvances%2Bin%2BSocial%2BSciences%3BPID%253D2017-5-4-8

[29] https://www.jatland.com/home/The_Jats:Their_Origin%2C_Antiquity_and_Migrations/Jat-Its_variants

[30] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zu%E1%B9%AD%E1%B9%AD

[31] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zutt_Rebellion

[32] https://www.reddit.com/r/AcademicQuran/comments/1az7rlx/south_asians_zutt_in_early_muslimarab_society/

[36] https://www.jstor.org/stable/44141246

[39] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zutt_Rebellion

[40] https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Zutt_Rebellion

[44] https://www.jstor.org/stable/259518

[45] https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/abstract/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-933

[46] https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Zutt_Rebellion

[47] https://www.reddit.com/r/AcademicQuran/comments/1az7rlx/south_asians_zutt_in_early_muslimarab_society/

[49] https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-933

[51] https://m.facebook.com/abdulkadir.ibrahimango/photos/sheikh-muhammad-bin-uthmansheikh-muhammad-bin-uthman-was-a-rebel-leader-who-play/1337512010619396/

[52] https://ijassonline.in/HTML_Papers/International%2520Journal%2520of%2520Advances%2520in%2520Social%2520Sciences__PID__2017-5-4-8.html

[63] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jat_people