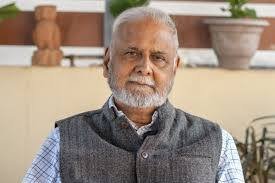

Jagdeep S. Chhokar (1944–2025) was an academic, engineer, lawyer, bird-watcher and one of the founding members of the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR). Over five decades his career moved from engineering and management scholarship to citizen activism that changed the rules of Indian elections — making candidate disclosure and transparency routine, and repeatedly pressing courts to rein in opaque political finance and appointment processes. This long-form piece traces his life from early training as an engineer to his years at IIM-Ahmedabad, his role in ADR and the major legal and policy battles ADR initiated or supported. It also assesses his legacy and the institutional changes his work helped produce.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction — Why his story matters

Jagdeep S. Chhokar belonged to a small group of scholar-activists whose scholarly skills, methodological rigor and willingness to litigate brought measurable institutional reforms to Indian democracy. He blended technical training (engineering, management) with legal knowledge and citizen activism to build tools and cases that forced electoral institutions and political actors to be more transparent and accountable. The story of Chhokar is therefore both the biography of an individual and a case study in how rigorous data, public interest litigation, and patient advocacy can reshape democratic practice. archives.iima.ac.in+1

2. Early life and education

Jagdeep S. Chhokar was born on 25 November 1944 (multiple profiles and obituaries record his birth year) and his early trajectory reflects an unusual breadth of professional training. He first trained as a mechanical/production engineer, completing graduate work in engineering in 1967. After working as an engineer (including a stint with the Indian Railways), he pursued an MBA from the University of Delhi (1977) and then a Ph.D. in Management and Organisational Behaviour from Louisiana State University (awarded 1983). Later in life he added a law degree (LL.B.) from Gujarat University (2005). This mix — engineering, management research, and law — equipped him with a rare interdisciplinary toolkit that he used during his academic career and later in democratic reform work. archives.iima.ac.in+1

Personal interests such as ornithology (he obtained a certificate in ornithology from the Bombay Natural History Society in 2001) were more than hobbies; observers say they reflected a patient, observational temperament that carried over into his empirical approach to public advocacy. archives.iima.ac.in

3. Academic career: IIM Ahmedabad and the scholar-teacher

Chhokar joined the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad (IIMA) in 1985 in the Organizational Behaviour area and remained a central member of the faculty until his retirement in November 2006. He served as Dean (2001–02) and as Director-in-charge (July–September 2002). Colleagues remember him as a rigorous teacher, a careful researcher and an administrative leader who combined scholarship with public engagement. His academic interests covered management, organizational behaviour and institutions — domains where his later civic interventions (transparency, accountability) drew on both theoretical grounding and empirical methods. archives.iima.ac.in+1

His academic profile is notable for how steadily it evolved from technical domains (engineering) to social science and law — an arc mirrored in his public interventions which married empirical data with legal strategy. archives.iima.ac.in

4. From classroom to civic courtroom: the origins of ADR

The Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) was founded in 1999 by a group of academics and citizens — including Jagdeep S. Chhokar and his IIM-Ahmedabad colleagues such as Trilochan Sastry and others — who were alarmed by the increasing criminalization of politics and the secrecy surrounding candidate backgrounds and political funding. ADR began as a campaign for basic disclosure: that candidates for Parliament and state assemblies should reveal their criminal records, assets, liabilities and educational qualifications at the time of filing nominations. That demand was pursued both as public education (collecting and publishing data) and as litigation (Public Interest Litigation seeking formal changes). ADR India+1

Chhokar played a central role not only as an institutional founder but as a scholar-advocate — applying rigorous data collection and analysis to build court cases, media reports and voter-information platforms (such as MyNeta) that could be used by citizens, journalists and the judiciary. The strategy was to make the invisible visible: if candidate disclosures were available and widely publicized, voters would be empowered and political incentives would slowly shift. ADR India+1

5. Major legal and policy victories — ADR’s strategic litigation (and Chhokar’s role)

ADR’s litigation strategy, in which Chhokar was a key intellectual and organizational force, targeted several structural deficits in India’s electoral system. Below are the major cases and reforms that ADR helped secure — each entry includes a short explanation of the issue, the ADR intervention and the outcome.

Note: ADR’s own litigation pages and contemporary Supreme Court/High Court reports provide the authoritative record; the summary below follows ADR’s listing and major media coverage. ADR India+1

5.1 Mandatory disclosure of candidate affidavits (PIL, Delhi High Court → Supreme Court rulings, 2000–2003)

Issue: Candidates did not have to publicly disclose criminal cases, assets or educational qualifications; voters lacked reliable, standardized information.

ADR intervention: A PIL by a group of IIM professors and civil society (which included Chhokar) in the Delhi High Court sought mandatory disclosure.

Outcome: The Delhi High Court ruled in favour of disclosure; after appeals, the Supreme Court (landmark judgments in 2002 and 2003) made it mandatory for contesting candidates to file affidavits disclosing criminal, financial and educational backgrounds. This institutionalized what is now accepted practice — candidate affidavits and their publication by the Election Commission and civil society databases (MyNeta/ADR). The judgments are foundational to ADR’s later work. Wikipedia+1

5.2 Political party and candidate expenditure monitoring (various petitions)

Issue: Party and candidate expenditure was inadequately monitored and enforced; opaque spending undermined fairness.

ADR intervention: ADR filed petitions seeking systematic audit and transparency in election expenditure, and pressed for better enforcement mechanisms.

Outcome: Judicial attention and incremental reforms followed, with ADR’s litigation nudging election authorities toward stronger monitoring and better reporting frameworks. (ADR maintains a running summary of petitions and judgments its advocacy triggered.) ADR India+1

5.3 Electoral Bonds and corporate funding of political parties (petition culminating in major Supreme Court ruling)

Issue: The Electoral Bonds scheme (introduced by the Finance Act) allowed anonymous, large political donations routed through banks, limiting public scrutiny of who funds parties.

ADR intervention: ADR challenged the constitutionality of anonymous electoral bonds and related amendments that removed limits on corporate donations, arguing that anonymous, unregulated funding undermined transparency and democratic accountability.

Outcome: The Supreme Court issued a major decision holding that anonymous electoral bonds and the reported architecture enabling unregulated corporate donations were constitutionally problematic; parts of the scheme were struck down or heavily criticized by the judiciary. The litigation represented one of ADR’s most consequential interventions into the political-finance architecture. Wikipedia+1

5.4 Appointment of Election Commissioners — ensuring institutional independence (2023 petition)

Issue: The Executive branch’s exclusive role in appointing the Chief Election Commissioner and Election Commissioners raised concerns about independence and constitutional propriety.

ADR intervention: ADR petitioned the Supreme Court arguing for a more transparent, consultative appointment mechanism.

Outcome: In a landmark judgment the Supreme Court directed that appointments be made on the recommendation of a committee comprising the Prime Minister, the Chief Justice of India and the Leader of the Opposition (or leader of the single largest opposition party) in the Lok Sabha — strengthening procedural safeguards for independence. Wikipedia

5.5 VVPAT and EVM transparency issues (post-2014 litigation)

Issue: Concerns about electronic voting machines (EVMs) and the reliability of VVPAT (Voter-verified paper audit trail) led to demands for more robust verification procedures.

ADR intervention: ADR filed petitions seeking stronger audit and verification mechanisms, including counting VVPATs in a manner that increases public confidence while balancing administrative feasibility.

Outcome: The Supreme Court issued directions related to sealing and storing certain EVM components and setting cross-verification mechanisms following elections; ADR’s petitions were central to that jurisprudential strand. Wikipedia

5.6 Other petitions and interventions (party funding, FCRA matters, asset declaration rules, etc.)

ADR’s litigation record is broad — spanning petitions on Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA) amendments that affected political funding, petitions seeking more disclosure from parties and candidates, and interventions on matters of public interest that intersect with democratic processes. The organisation’s legal and advocacy archive catalogs these cases and their judgments. ADR India+1

6. A consolidated list of important ADR cases / petitions (selected)

Below is a selection of the most consequential petitions and orders associated with ADR’s advocacy. This is not an exhaustive list but highlights the high-impact matters that reshaped disclosure, appointments and funding rules.

- PIL for disclosure of candidate affidavits (1999–2003) — Delhi High Court → Supreme Court decisions making affidavits mandatory. Wikipedia

- Petitions on party funding and electoral bonds (2017–2024) — challenging anonymity in political funding; major Supreme Court scrutiny and rulings. Wikipedia+1

- Petition on appointment procedure for Election Commissioners (2023) — Supreme Court directed a committee-based appointment process. Wikipedia

- Petitions regarding EVM/VVPAT verification and audit (2019–2024 period) — directives on EVM components, sealing and cross-verification. Wikipedia

- Petitions on monitoring election expenditure and party accounts — notices and orders for improved financial monitoring of parties and better enforcement of expenditure rules. ADR India

- Interventions on asset and income declaration rules (spouses and dependents) — securing more comprehensive disclosure norms. Wikipedia

For a comprehensive and authoritative list (with case citations and links to orders) ADR’s own legal-advocacy pages and judgment lists are the primary resource. They include scanned judgments, order summaries and press releases that document each petition’s procedural history and legal reasoning. ADR India+1

7. Methods: how Chhokar and ADR built persuasive public-interest cases

Three features defined their strategic edge:

- Empirical rigor. ADR did not litigate in the abstract. It collected, cleaned and publicly published candidate affidavits and analysis (criminal charges, assets, education). This empirical basis made petitions concrete and hard to dismiss as merely ideological. The MyNeta portal and ADR reports provided accessible, replicable datasets. MyNeta+1

- Combined legal and public advocacy. ADR’s strategy combined courtroom petitions with media campaigns and educational outreach. Bringing data to public attention changed the political incentives — parties and candidates faced reputational costs when their affidavits revealed troubling material. ADR India

- Institutional patience and incrementalism. Rather than seeking a single sweeping fix, ADR pursued incremental reforms (disclosure, better audits, appointment rules), each of which lowered barriers to the next reform. Chhokar’s academic temperament — careful, evidence-based, patient — was a strong fit for this approach. Business Standard

8. Public perception, controversies and pushback

No reform movement is free from controversy. ADR’s litigation often drew pushback from political parties and some commentators who argued that judicialisation of political reform risks substituting technocratic fixes for political debate. There were also tactical controversies — for instance, debates over whether disclosure alone suffices without enforcement, or whether ADR’s empirical framing sometimes simplified complex social and political factors. ADR and Chhokar responded by emphasizing transparency as a precondition for democratic accountability rather than a panacea on its own. Media coverage and legal commentary document both praise and critique; nevertheless, courts repeatedly accepted ADR’s core premise: voters have a right to factual information about those seeking office. The Wire+1

9. Personal life, interests and temperament

Beyond law and policy, Jagdeep Chhokar was widely described as a person of varied interests and gentle temperament. A trained mechanic-engineer turned academic, later a qualified lawyer, he was also known for birding (ornithology certificate from BNHS) and conservation interests. Colleagues emphasize his methodical approach to problems, his patient attention to evidence and his belief that citizens — properly informed and organised — can hold institutions to account. Obituaries emphasize his humility and the unexpected combination of scholar, practitioner and activist in the same person. archives.iima.ac.in+1

On the matter of caste: public obituaries, institutional biographies and ADR’s materials provide a detailed account of Chhokar’s education, career and public work but do not present a reliable, authoritative statement of his caste or community background. Available mainstream sources focus on his professional life and public interventions; therefore, it would be inaccurate to assert a caste identity in the absence of primary documentation or a statement from Chhokar himself or his family. Where caste or community is relevant in public records, responsible reporting relies on explicit, sourced claims; none of the authoritative institutional profiles (IIMA archives, ADR, major obituaries) foreground a caste label. In short: public sources do not reliably document his caste; responsible reporting avoids speculation. archives.iima.ac.in+1

10. Awards, recognitions and institutional roles

Chhokar’s academic appointments (Dean and Director-in-charge at IIMA) and his role as a founding member of ADR are the principal institutional recognitions most cited. He was regularly consulted by policymakers, media and civil society as an expert on electoral governance. He also wrote widely — including opinion pieces and blog posts — on reservations, governance and democracy. Obituaries and profiles praise the combination of scholarship and activism as his most enduring contribution. archives.iima.ac.in+1

11. Impact assessment — what changed because of Chhokar and ADR?

An impact assessment can be divided into measurable institutional changes and harder-to-quantify cultural shifts.

Measurable institutional changes

- Mandatory candidate affidavits: Voters now routinely have access to candidate criminal records, assets and education — a direct outcome of the litigation strategy. This data has been used by journalists, watchdogs and courts in countless follow-up inquiries. Wikipedia+1

- Policy and judicial scrutiny of political finance: ADR’s petitions contributed to the Supreme Court taking electoral bonds and anonymous funding seriously, producing rulings that curtailed or reformed the architecture of anonymous funding. Wikipedia

- Appointment safeguards for election commissioners: The committee-based appointment direction strengthened procedural protections for the Election Commission’s independence. Wikipedia

Cultural shifts

- Normalization of data-driven civic oversight: ADR’s model — systematic collection and public release of candidate data — normalized the idea that informed citizens can and should use data to hold power accountable.

- Rise of media and NGO collaborations: ADR’s publicly available databases made evidence usable by journalists and researchers, strengthening the ecosystem of watchdog journalism.

These outcomes illustrate how careful empirical work, when combined with strategic litigation and outreach, can produce both immediate reforms and durable shifts in democratic culture. ADR India+1

12. Critiques, limits and ongoing problems

Chhokar and ADR never claimed that disclosure alone would solve deep political problems. Critics and some scholars emphasize persistent limits:

- Enforcement gaps. Disclosure is only as valuable as the enforcement that follows when candidates falsify affidavits or when investigators fail to follow through.

- Political finance remains evasive. Even with judicial rulings, new mechanisms can appear to route funds or avoid transparency.

- Judicialisation vs political reform. Some observers worry that heavy reliance on courts can displace political debate and democratic contestation — but ADR’s stance has always been that the law and courts are instruments to correct procedural deficits, not substitutes for politics.

These limits shaped ADR’s subsequent advocacy: after winning disclosure rules, the organisation invested in data verification, public education and follow-up petitions that press for enforcement and systemic change. ADR India+1

13. Final years and legacy

Jagdeep S. Chhokar continued to be active as an adviser, writer and public intellectual after his formal retirement from IIMA in 2006. His later decades were marked by constant public engagement: writing, advising ADR, testifying in public fora and giving interviews. When he passed away in 2025 (reported widely in national media), obituaries noted two intertwined legacies: his contributions to management education, and his role in building ADR into a durable civic institution that brought lasting transparency to electoral life. Commentators stressed that his greatest gift was institutional — creating data tools and legal precedents that will enable future citizens and reformers to continue the work. Business Standard+1

14. Resources and further reading

- Jagdeep S. Chhokar — Faculty profile, IIM Ahmedabad archives (institutional biography and academic CV). archives.iima.ac.in

- Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) — official website, legal advocacy and judgments pages (comprehensive case list and judgments). ADR India+1

- Media obituaries and profiles summarising Chhokar’s work: The Wire, Business Standard, Times of India, The New Indian Express (reports and analyses posted in September 2025). The Wire+2Business Standard+2

- MyNeta (myneta.info) — public database of candidate affidavits and ADR-related data. MyNeta

15. Conclusion — an institutional legacy more than a personality cult

Jagdeep S. Chhokar’s life illustrates a particular model of public engagement: scholarly rigour channeled into institutional reform. Rather than seeking charismatic leadership or short-term denunciations, Chhokar helped build data systems, legal precedents and civic norms that make transparency an expectation rather than an exception. ADR’s long litigation record, the routine publication of candidate affidavits and heightened judicial attention to political finance and appointment processes are tangible outcomes that will shape Indian public life well beyond his lifetime.

If one wants to sum up his contribution in a single phrase: he turned the problem of “opaque politics” into a problem of “missing data and weak procedures,” and then set about collecting the data and fixing the procedures — a subtle but powerful re-framing whose consequences will keep playing out for decades.