Introduction

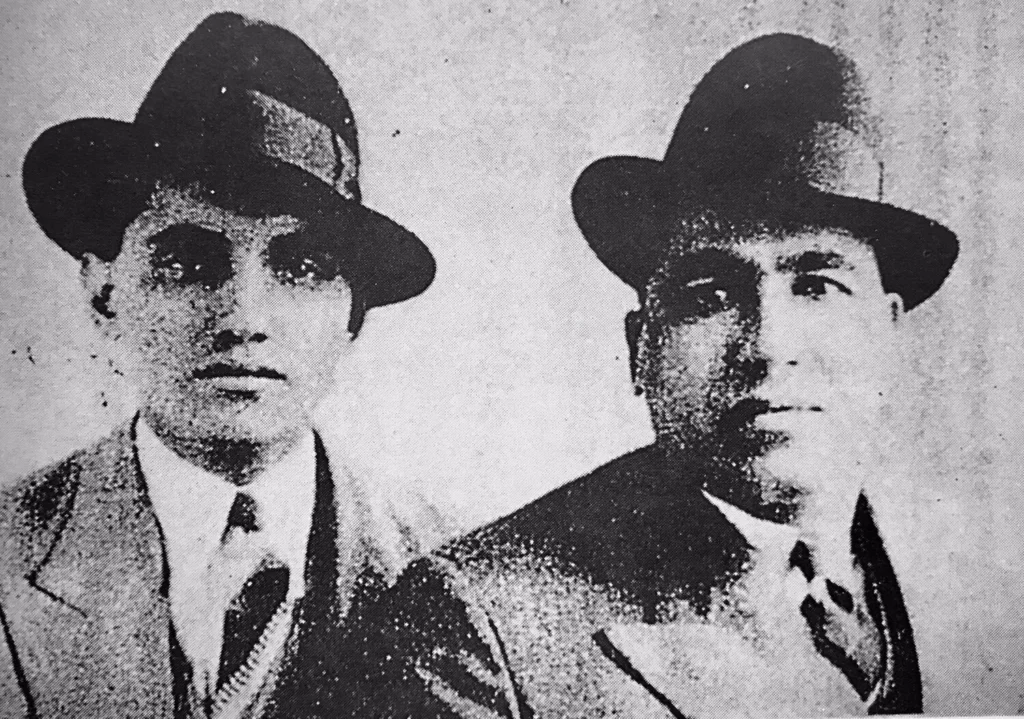

Shaheed Udham Singh (born Sher Singh; 26 December 1899 – 31 July 1940) was an Indian revolutionary whose life exemplified patience, sacrifice, and unyielding defiance against British colonialism. He is best remembered for assassinating Sir Michael Francis O’Dwyer, the former Lieutenant Governor of Punjab, on 13 March 1940 in London’s Caxton Hall – exactly 21 years after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, which O’Dwyer had endorsed. Udham Singh’s act was a deliberate revenge for the massacre he witnessed as a young man.

Table of Contents

During his arrest and trial, he adopted the name Ram Mohammad Singh Azad (or variations like Mohammad Singh Azad), symbolizing Hindu-Muslim-Sikh unity in the fight for freedom (“Azad” meaning “free”). This alias, tattooed on his arm and insisted upon in court, reflected his secular vision of a united India.

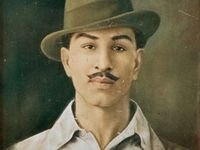

Profoundly influenced by Shaheed Bhagat Singh, whom he regarded as his “guru” and “best friend,” Udham Singh carried forward the revolutionary tradition of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) and Ghadar Party. His prison letters reveal deep admiration for Bhagat Singh, expressing hope to meet him after death.

This revised article draws on primary sources (trial transcripts, prison letters, British archives) and scholarly works to provide historical evidence, addressing debates such as his presence at Jallianwala Bagh and the exact form of his alias.

Early Life: From Orphanage to Radicalization

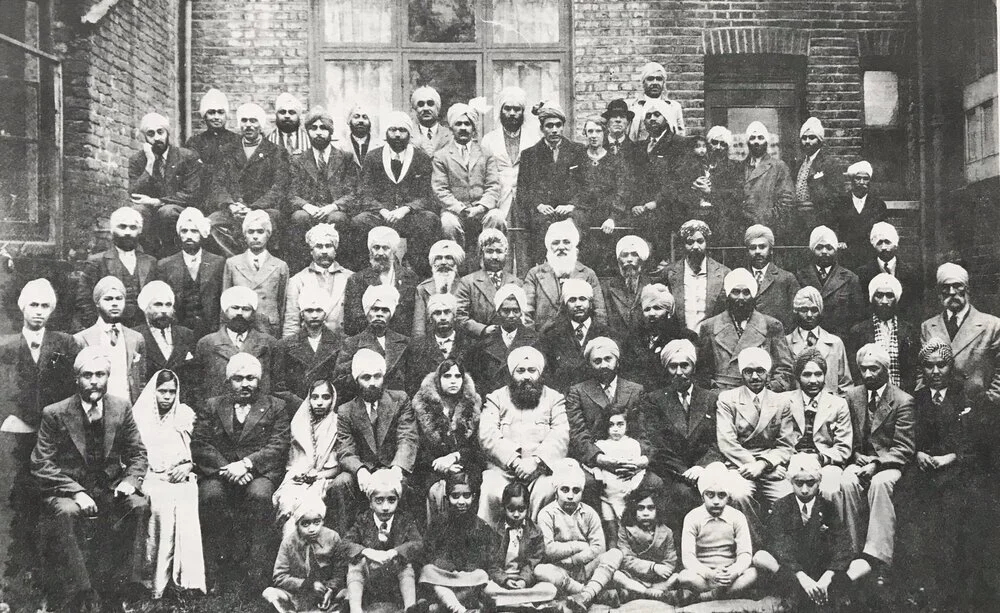

Udham Singh was born Sher Singh on 26 December 1899 in Sunam, Sangrur district, Punjab, to Tehal Singh (a railway crossing watchman) and Narain Kaur, in a Kamboj Sikh family. Orphaned young – mother early, father in 1907 – he and his brother Sadhu Singh were admitted to the Central Khalsa Orphanage in Amritsar on 24 October 1907. During Sikh initiation, he was renamed Udham Singh.

The orphanage register confirms these details. Growing up in Amritsar amid rising anti-colonial sentiment (Komagata Maru incident, Ghadar uprising), he absorbed revolutionary ideas early.

He briefly served in the British Indian Army during World War I (32nd Sikh Pioneers, Basra), returning disillusioned.

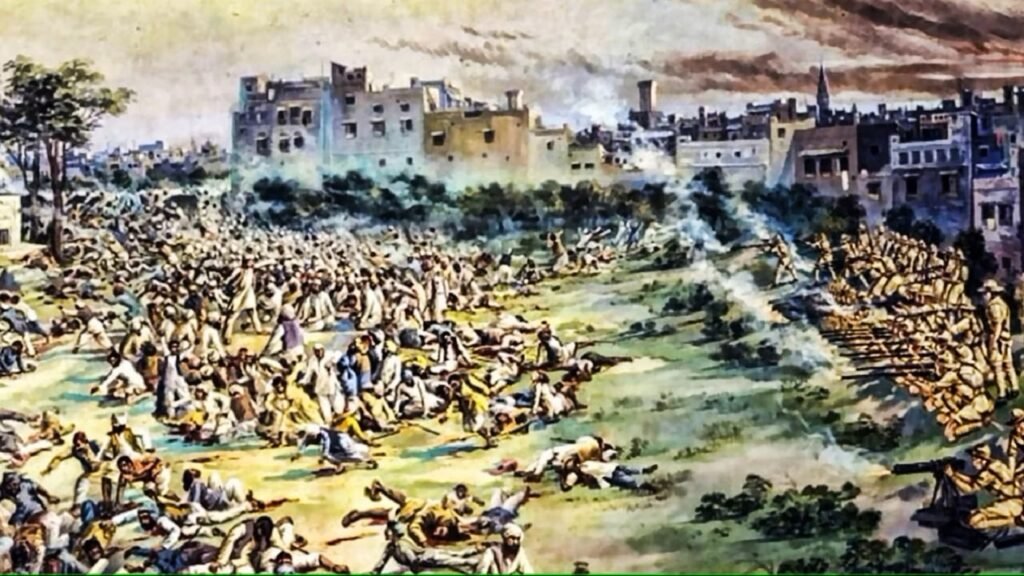

The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre: A Lifelong Scar

On 13 April 1919 (Baisakhi), Udham Singh, aged 19-20, was at Jallianwala Bagh. Traditional accounts state he volunteered from the orphanage to serve water to protesters against the Rowlatt Act. He witnessed Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer’s troops fire on the trapped crowd, killing hundreds (official: 379; Congress estimate: over 1,000).

Many sources affirm he was present, helping the wounded and collecting blood-soaked soil as a vow of revenge. V.K. Krishna Menon (his trial defender) cited instances confirming his presence. However, recent debates (e.g., Punjab school textbook controversy) question if he arrived post-massacre. Anita Anand’s The Patient Assassin (2019) notes inconsistencies in his later claims but affirms the event’s profound impact, turning personal grief into revolutionary resolve.

O’Dwyer defended Dyer’s actions, fueling Udham’s hatred.

Revolutionary Path and Ghadar Party Involvement

Post-massacre, Udham joined revolutionary circles, influenced by Ghadar Party ideology. In 1924, he traveled abroad (Africa, US), propagating Ghadar ideas and working odd jobs.

Evidence of Ghadar links: In 1927, on Bhagat Singh’s orders, he returned with arms/ammunition and associates. Arrested in Amritsar, convicted under Arms Act (possessing Ghadar literature like Ghadr-di-Gunj), sentenced to five years.

Released 1931, evaded surveillance, fled to Europe, settling in London (1934) under aliases (e.g., Frank Brazil).

The Enduring Influence of Shaheed Bhagat Singh

Udham Singh’s ideology was profoundly shaped by Bhagat Singh. He met him in jail (likely Lahore/Mianwali, 1927-1931), calling him “guru” and “best friend.” He carried Bhagat’s portrait, tattooed references, and was influenced by his atheism, socialism, and secularism.

Primary evidence: Prison letters (Brixton, 1940), now at Guru Nanak Dev University, express longing to die on Bhagat’s hanging date (23 March 1931) and meet him afterlife. “I am sure after my death I will see him as he is waiting for me.”

Bhagat’s court defiance inspired Udham’s trial speech. Both used platforms for anti-imperial propaganda.

Key influences:

- Revolutionary Zeal and Sacrifice: Bhagat’s willingness to die young (“better to die young than grow old without achievement”) mirrored in Udham’s patience and final act.

- Secularism and Unity: Bhagat’s atheism and anti-communalism inspired Udham’s alias “Ram Mohammad Singh Azad,” symbolizing interfaith harmony against colonialism.

- Armed Resistance: Bhagat’s shift from non-violence to direct action validated Udham’s path.

- Trial as Propaganda: Both used courts to expose British injustice. Udham’s suppressed speech echoed Bhagat’s famous statements.

Bhagat Singh’s Ideological Impact

- Socialism: Both drawn to Marxist ideas via Ghadar/HSRA links to Comintern.

- Atheism vs. Spirituality: Bhagat’s atheism influenced Udham, who transcended religious identity.

- Internationalism: Udham’s global travels echoed HSRA’s broader anti-imperialism.

Historians note Udham emulated Bhagat’s court defiance and youthful martyrdom.

Preparation and the Assassination

From 1934-1940, Udham lived nomadically in London, working as laborer/peddler, tracking O’Dwyer. On 13 March 1940, at Caxton Hall, he shot O’Dwyer twice, killing him. He wounded others but surrendered calmly, stating: “I did it because I had a grudge against him. He deserved it.”

He insisted on name “Ram Mohammad Singh Azad” (or Mohammad Singh Azad), symbolizing communal unity. Police noted: “a co-ordination of the Mohamedan and Hindu Faiths” (with Sikh “Singh”).

Trial, Suppressed Speech, and Martyrdom

Charged with murder, Udham’s trial at Old Bailey (June 4–5, 1940) became a platform. He insisted on “Ram Mohammad Singh Azad” as his name.

When asked if he had anything to say before sentencing, Udham delivered a fiery political speech, interrupted repeatedly by Justice Atkinson, who ordered it suppressed.

Key excerpts from the released transcript (published 1996 after campaigns):

- “I am not afraid to die. I am proud to die… I hope that when I am gone, thousands of my countrymen will come to drive you dirty dogs out; to free my country.”

- “Machine guns killed the people in Jallianwala Bagh… You are responsible for this.”

- Criticizing British imperialism: “We are suffering from the British Empire… Down with British dirty dogs!”

He shouted “Inquilab Zindabad!” (Long Live Revolution) thrice upon sentencing.

Udham went on a 42-day hunger strike in Brixton Prison. Appeal dismissed July 15, 1940.

Hanged at Pentonville Prison on July 31, 1940. His last words reportedly joyful, following Bhagat’s example.

British buried him in prison grounds; ashes repatriated in 1974, scattered in Sutlej and Jallianwala Bagh.

Legacy

Udham Singh’s act symbolized resistance. Nehru saluted him; districts/towns named after him. Films: Sardar Udham (2021).

His unity symbol and Bhagat-inspired defiance endure.

In-Depth: Alias and Presence Debates

Alias primarily “Mohammad Singh Azad” in records/trial; “Ram” added later for explicit Hindu inclusion.

Presence at Bagh: Affirmed by contemporaries (Menon, orphanage accounts); debated but impact undisputed.

Conclusion

Udham Singh’s life – from orphan witness to patient avenger – embodies revolutionary sacrifice. Influenced by Bhagat Singh, he fulfilled a vow spanning decades.

References and Sources

- Anita Anand, The Patient Assassin (2019) – Primary research on archives, letters.

- Sikander Singh, Udham Singh alias Ram Mohammad Singh Azad (2002).

- Navtej Singh & Avtar Jouhl, Emergence of the Image: Redacted Documents of Udham Singh (2002) – Declassified files.

- Trial Transcript (Old Bailey, 1940) – Released archives; excerpts in Revolutionary Democracy.

- Udham Singh’s Prison Letters – Guru Nanak Dev University (Times of India reports).

- Britannica & Wikipedia (sourced entries).

- Indian Express, Times of India articles on debates/letters.

- British National Archives (declassified files).