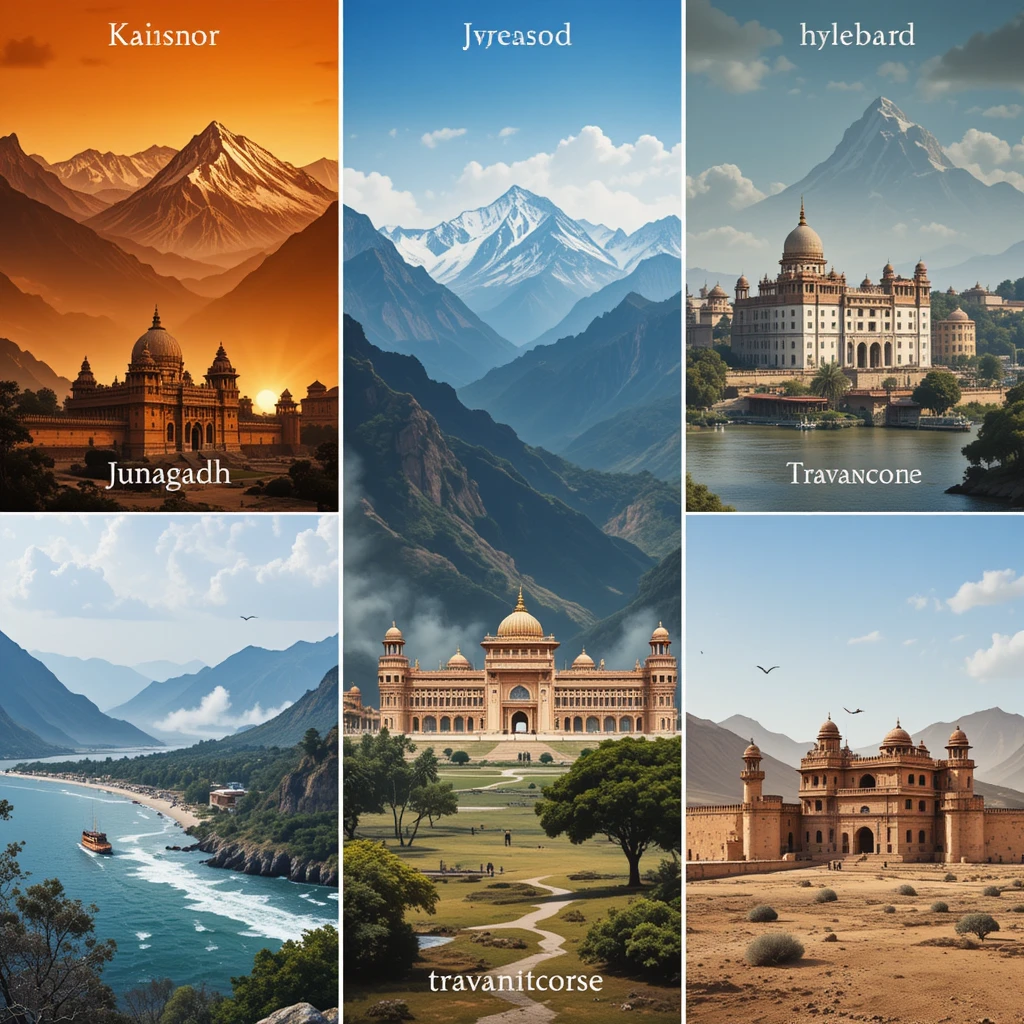

The partition of British India in 1947 into India (Integration of Princely States) and Pakistan left the fate of over 565 princely states, covering approximately 40% of the subcontinent’s territory, uncertain. These semi-autonomous entities, ruled by hereditary monarchs under British paramountcy, were given the choice to accede to India, Pakistan, or remain independent under the Indian Independence Act of 1947. The integration of these states into the Indian Union was a monumental task, orchestrated by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, India’s Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister, and V.P. Menon, his key aide. While most states acceded smoothly, Jammu and Kashmir, Junagadh, Hyderabad, Travancore, and certain Rajputana states like Jodhpur posed unique challenges due to their rulers’ ambitions, demographic complexities, or geopolitical significance. This article explores the integration of these states, analyzing the diplomatic, military, and political strategies employed, the obstacles faced, and the enduring legacies of these processes.

Table of Contents

Historical Context

Princely states operated under British suzerainty, with rulers managing internal affairs while the British controlled defense, foreign relations, and communications. The lapse of paramountcy in 1947, as announced by the British, left these states in a political vacuum. Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy, advised rulers to accede to either India or Pakistan based on geographic contiguity and demographic composition, but the decision rested with the rulers, not the populace. This created tensions, as some rulers sought independence or alignment with Pakistan, clashing with India’s vision of a unified nation-state.

Sardar Patel’s Ministry of States, established in July 1947, spearheaded the integration process. Patel and Menon devised the Instrument of Accession, a legal document through which states ceded control over defense, external affairs, and communications to India while retaining internal autonomy (initially). Standstill Agreements maintained administrative status quo during negotiations. By August 15, 1947, most states had acceded to India, but Jammu and Kashmir, Junagadh, Hyderabad, Travancore, and certain Rajputana states required special attention due to their strategic importance or rulers’ resistance.

Case Studies of Integration

1. Jammu and Kashmir

Context: Jammu and Kashmir, ruled by Hindu Maharaja Hari Singh, was a Muslim-majority state (77% Muslim per the 1941 Census) bordering India and Pakistan. Its strategic location in the Himalayas made it a flashpoint. Hari Singh initially sought neutrality, wary of both India’s secular democracy and Pakistan’s Muslim-majority framework.

Integration Process:

- Hari Singh proposed standstill agreements with India and Pakistan to delay accession. Pakistan signed the agreement, but India did not, seeking clarity on Kashmir’s intentions.

- On October 22, 1947, Pakistan-backed tribal militias, supported by its army, invaded Kashmir, capturing Muzaffarabad and advancing toward Srinagar. The invasion aimed to force annexation or destabilize the state.

- Facing collapse, Hari Singh appealed to India for military aid. India, led by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Patel, conditioned assistance on accession. On October 26, 1947, Hari Singh signed the Instrument of Accession, ceding defense, external affairs, and communications to India. Indian troops were airlifted to Srinagar, repelling the invaders by late 1947.

- The conflict escalated into the first Indo-Pakistan War. India referred the issue to the United Nations on January 1, 1948, seeking condemnation of Pakistan’s aggression. The UN Security Council’s Resolution 47 (1948) called for a ceasefire, Pakistani withdrawal, and a plebiscite to determine Kashmir’s future, contingent on Pakistan’s compliance. Pakistan did not withdraw, and the plebiscite never occurred. A ceasefire in January 1949 established the Line of Control, leaving one-third of Kashmir (Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan) under Pakistani control.

- Kashmir was granted special autonomy under Article 370 of the Indian Constitution (1950), allowing its own constitution and flag. This status was revoked in 2019, integrating Kashmir fully into India.

Challenges:

- The Muslim-majority population complicated accession, as Pakistan expected Kashmir to join it based on the two-nation theory. Hari Singh’s indecision reflected fears of losing power in a democratic India or facing unrest in a Muslim-majority Pakistan.

- The tribal invasion forced a hasty accession, raising questions about its voluntariness. The UN’s unimplemented plebiscite resolution remains a point of contention.

- Sheikh Abdullah, leader of the National Conference, supported accession but demanded democratic reforms, creating tensions with Hari Singh.

Legacy: Kashmir’s integration remains unresolved, fueling Indo-Pakistan conflicts (1947, 1965, 1999) and insurgency in the Kashmir Valley. The 2019 revocation of Article 370 intensified debates over the accession’s legitimacy.

Critical Perspective: India views the Instrument of Accession as legally binding, supported by Sheikh Abdullah’s endorsement. Pakistan contests it, citing the Muslim majority and the unfulfilled plebiscite. The invasion’s role in forcing accession suggests coercion, though Hari Singh’s appeal to India was a sovereign act.

2. Junagadh

Context: Junagadh, a princely state in Gujarat’s Kathiawar peninsula, had a Hindu-majority population (80%) but was ruled by Muslim Nawab Muhammad Mahabat Khanji III. Its maritime proximity to Pakistan and lack of a land border with India shaped its ruler’s ambitions.

Integration Process:

- On September 15, 1947, the Nawab acceded to Pakistan, defying Mountbatten’s advice to prioritize geographic contiguity. His Dewan, Sir Shah Nawaz Bhutto, influenced this decision, hoping for Pakistan’s support.

- Two vassal states, Mangrol and Babariawad, declared independence and acceded to India. The Nawab occupied them militarily, prompting India to impose a blockade, cutting off fuel, coal, and communications.

- Public unrest grew among the Hindu majority, and a provisional government (Aarzi Hukumat), led by Samaldas Gandhi, was formed in Bombay to “liberate” Junagadh. On October 26, 1947, the Nawab fled to Karachi, emptying the state treasury. Bhutto, facing administrative collapse, invited India to take over on November 7, 1947.

- India assumed control on November 9, 1947, and held a plebiscite on February 24, 1948. Of 201,457 registered voters, 190,870 voted, with 99.95% favoring India.

Challenges:

- The Nawab’s accession to Pakistan was impractical due to geography (400 miles from Pakistan) and demographics. The Hindu majority opposed it, and India viewed it as a violation of partition principles.

- India’s blockade and military presence during the plebiscite raise questions about coercion, though the overwhelming vote reflected popular will.

Legacy: Junagadh’s integration was formalized, but Pakistan continues to claim it, citing the Nawab’s accession. The episode highlighted India’s willingness to use force to secure strategic territories.

Critical Perspective: The plebiscite’s near-unanimous result suggests genuine support for India, but the process was arguably influenced by India’s control. Pakistan’s claim lacks practical grounding, given Junagadh’s integration into Gujarat.

3. Hyderabad

Context: Hyderabad, the largest and wealthiest princely state, was ruled by Nizam Mir Osman Ali Khan, a Muslim presiding over a Hindu-majority population (85%). Located in India’s Deccan heartland, it sought independence or alignment with Pakistan.

Integration Process:

- The Nizam signed a Standstill Agreement with India in November 1947, seeking time to negotiate independence. He was supported by the Ittehadul Muslimeen and its militia, the Razakars, who resisted integration and targeted Hindus.

- Popular movements, including the Telangana peasant uprising and Hyderabad State Congress agitation, challenged the Nizam’s autocracy. Razakar violence destabilized the state, with reports of communal atrocities.

- Negotiations failed as the Nizam demanded sovereignty or dominion status. On September 13, 1948, India launched Operation Polo, a police action involving 35,000 troops. The Nizam’s forces and Razakars were defeated within five days, and Hyderabad surrendered on September 17, 1948.

- The Nizam signed the Instrument of Accession in November 1948 and was appointed Rajpramukh (Governor) of democratic Hyderabad, a conciliatory gesture.

Challenges:

- The Nizam’s ambition for independence clashed with India’s unification goals. The Razakars’ violence justified intervention, but Operation Polo’s scale (over 2,000 reported deaths) drew criticism.

- Communal tensions escalated post-operation, with reprisals against Muslims in Hyderabad.

Legacy: Hyderabad’s integration ended one of the most powerful princely regimes, paving the way for its reorganization into Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and parts of Karnataka. The Nizam’s descendants retained ceremonial influence.

Critical Perspective: India’s narrative emphasizes the Nizam’s misrule and Razakar atrocities to justify Operation Polo. However, the operation’s human cost and communal fallout highlight the complexities of forced integration. The Nizam’s initial resistance reflected genuine fears of losing power, but his reliance on the Razakars alienated the majority.

4. Travancore

Context: Travancore, a maritime state in southern India (modern Kerala), was ruled by Maharaja Chithira Thirunal. Its Dewan, Sir C.P. Ramaswamy Aiyar, envisioned independence, leveraging Travancore’s monazite deposits (valuable for nuclear technology) and strategic Arabian Sea location.

Integration Process:

- In 1946, Aiyar declared Travancore’s intent to remain independent, possibly with a treaty with India. He sought British support, offering monazite access in exchange for autonomy.

- Nehru invited Aiyar to Delhi for negotiations, but he resisted signing the Instrument of Accession. Aiyar’s anti-communist stance made him unpopular with local communists and Congress supporters.

- On July 25, 1947, an assassination attempt on Aiyar shifted the dynamics. From his hospital bed, he advised the Maharaja to accede to India. On July 30, 1947, Travancore signed the Instrument of Accession.

- Travancore merged with Cochin in 1949 to form Travancore-Cochin, a precursor to modern Kerala.

Challenges:

- Aiyar’s ambition for independence stemmed from Travancore’s economic self-sufficiency and strategic resources. The assassination attempt highlighted internal opposition, forcing a pragmatic decision.

- Rumors of British interest in monazite complicated negotiations, though evidence is limited.

Legacy: Travancore’s integration was relatively smooth, contributing to Kerala’s formation. The episode underscored the fragility of princely ambitions in the face of national pressures.

Critical Perspective: The assassination attempt was a turning point, suggesting that internal dissent, not just Patel’s diplomacy, drove accession. Aiyar’s vision of independence was ambitious but unrealistic, given India’s determination to unify.

5. Rajputana (Rajasthan) States

Context: Rajputana comprised 21 princely states, including Jodhpur, Bikaner, Jaipur, and Udaipur, ruled by Hindu Rajput Maharajas with Hindu-majority populations. Their integration varied due to rulers’ ambitions or external overtures.

Integration Process:

- Bikaner and Jaipur: Progressive rulers like Bikaner’s Sadul Singh and Jaipur’s Sawai Man Singh II acceded to India in April–August 1947, recognizing the benefits of a unified nation. Bikaner signed the Instrument of Accession on April 7, 1947.

- Jodhpur: Maharaja Hanwant Singh, young and impressionable, briefly considered joining Pakistan, lured by Jinnah’s offers of a blank cheque, access to Karachi’s port, and military support. Jodhpur’s border with Pakistan made this tempting. Patel intervened, offering rail connectivity, arms imports, and food security during famines. The Diwan of Bikaner also persuaded the Maharaja. On August 11, 1947, Jodhpur acceded to India.

- Udaipur and Smaller States: Udaipur’s Maharana Bhupal Singh acceded in 1948, followed by smaller states like Dungarpur and Banswara. By 1949, multiple mergers created the United State of Rajasthan, finalized on May 15, 1949.

Challenges:

- Jodhpur’s flirtation with Pakistan risked destabilizing Rajasthan, given its strategic location. Smaller states feared losing autonomy, but Patel’s assurances of privy purses and governorships ensured compliance.

- The multiplicity of states required phased mergers, complicating administration.

Legacy: Rajasthan’s integration created a unified state, preserving Rajput cultural identity within India’s federal structure. The abolition of privy purses in 1971 sparked resentment among former rulers.

Critical Perspective: Jodhpur’s brief tilt toward Pakistan highlights the fluidity of princely decisions, driven by personal incentives. Patel’s diplomacy, offering tangible benefits, was key to Rajasthan’s seamless integration.

Broader Analysis

Sardar Patel’s Strategy

Patel’s approach combined:

- Diplomacy: Offering privy purses (annual stipends), governorships (e.g., Nizam as Rajpramukh), and assurances of autonomy (e.g., Article 370 for Kashmir).

- Incentives: Infrastructure support (e.g., Jodhpur’s rail connectivity) and economic aid.

- Force: Blockades (Junagadh) and military action (Hyderabad) when negotiations failed.

- Legal Framework: The Instrument of Accession and Standstill Agreements provided a standardized process, ensuring legal legitimacy.

Challenges

- Rulers’ Ambitions: The Nizam, Aiyar, and Hari Singh sought independence, reflecting fears of losing power in a democratic India.

- Communal Dynamics: Muslim rulers of Hindu-majority states (Junagadh, Hyderabad) or Hindu rulers of Muslim-majority states (Kashmir) faced communal pressures, exploited by Pakistan.

- Geopolitical Stakes: Kashmir and Junagadh became Indo-Pakistan flashpoints, while Hyderabad’s central location made its integration non-negotiable.

- Public Sentiment: Popular movements (e.g., Telangana uprising, Aarzi Hukumat) often aligned with India, pressuring rulers to accede.

Outcomes

By 1950, 562 of 565 princely states were integrated into India, either as standalone units or merged into larger entities like Saurashtra (Kathiawar states), Rajasthan, or Travancore-Cochin. The process unified India but left unresolved disputes, notably in Kashmir.

Critical Perspective

The integration narrative is often celebrated as a triumph of Indian unity, with Patel as the “Iron Man” who forged a nation. However:

- Coercion vs. Consent: India’s use of blockades (Junagadh) and military action (Hyderabad) suggests coercion, challenging the “voluntary accession” narrative. Plebiscites, where held, were conducted under Indian oversight, raising questions about impartiality.

- Communal Lens: The focus on Hindu-majority vs. Muslim-ruler dynamics oversimplifies local politics. For instance, Hyderabad’s Telangana uprising was as much anti-Nizam as pro-India.

- Kashmir’s Exception: Unlike other states, Kashmir’s integration remains contested, with Article 370’s revocation in 2019 reigniting debates over its accession’s legitimacy.

- British Legacy: The British policy of indirect rule left princely states ill-prepared for democratic integration, forcing India to navigate a patchwork of autocracies.

- Human Cost: Operation Polo’s violence and communal reprisals in Hyderabad highlight the darker aspects of integration, often glossed over in nationalist narratives.

Conclusion

The integration of Jammu and Kashmir, Junagadh, Hyderabad, Travancore, and Rajputana states was a defining moment in India’s nation-building. Patel’s strategic blend of persuasion, incentives, and force unified a fragmented subcontinent, but the process was fraught with challenges. Kashmir’s accession, driven by invasion, remains a geopolitical flashpoint; Junagadh’s plebiscite resolved its fate but not Pakistan’s claims; Hyderabad’s annexation ended Nizam rule at a human cost; Travancore’s swift turnaround reflected pragmatic surrender; and Rajasthan’s integration, despite Jodhpur’s waver, showcased diplomatic finesse. These episodes highlight the complexities of unifying a diverse nation, leaving legacies that continue to shape South Asian geopolitics.

References

- Menon, V.P. (1956). The Story of the Integration of the Indian States. Orient Longman.

- A primary account by Patel’s aide, detailing the diplomatic and legal processes of integration.

- Hodson, H.V. (1969). The Great Divide: Britain-India-Pakistan. Hutchinson.

- Provides a comprehensive history of partition and princely state negotiations.

- Guha, Ramachandra (2007). India After Gandhi: The History of the World’s Largest Democracy. Pan Macmillan.

- Offers a scholarly analysis of post-independence integration, including Kashmir and Hyderabad.

- Copland, Ian (1997). The Princes of India in the Endgame of Empire, 1917–1947. Cambridge University Press.

- Examines princely states’ political dynamics and integration challenges.

- Raghavan, Srinath (2010). War and Peace in Modern India. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Focuses on Kashmir and Hyderabad, analyzing India’s strategic decisions.

- Government of India, Ministry of States (1948). White Paper on Indian States.

- Official documentation of accession processes and Instruments of Accession.

- Chandra, Bipan et al. (1989). India’s Struggle for Independence. Penguin Books.

- Contextualizes popular movements like the Telangana uprising.

- Noorani, A.G. (2014). The Kashmir Dispute, 1947–2012. Oxford University Press.

- A detailed study of Kashmir’s accession and its aftermath.

- Snedden, Christopher (2015). Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris. Hurst & Company.

- Provides a balanced perspective on Kashmir’s integration and Pakistan’s role.

- Zutshi, Chitralekha (2004). Languages of Belonging: Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir. Permanent Black.

- Analyzes Kashmir’s socio-political context during accession.

Web Sources

- National Archives of India (www.nationalarchives.nic.in): Contains digitized Instruments of Accession and correspondence.

- United Nations Security Council Resolutions (www.un.org): UN Resolution 47 on Kashmir.

- Indian Ministry of External Affairs (www.mea.gov.in): Official statements on Kashmir and Junagadh.