Introduction

Maharaja Surajmal- In the swirling vortex of 18th-century Indian politics, where empires crumbled and new powers emerged from the ashes, few figures stand out as prominently as Maharaja Surajmal of Bharatpur. A leader of the Jat community, Surajmal (born February 13, 1707, and passing on December 25, 1763) navigated a landscape riddled with Mughal decline, Afghan invasions, and Maratha ambitions. His most celebrated feat—the seizure of the Agra Fort on June 12, 1761—marked not just a military victory but a symbolic reclamation of authority in the fertile Doab plains between the Ganga and Yamuna rivers. This event, following a grueling month-long encirclement starting May 3, 1761, underscored the Jats’ transition from agrarian insurgents to a formidable regional force.

Table of Contents

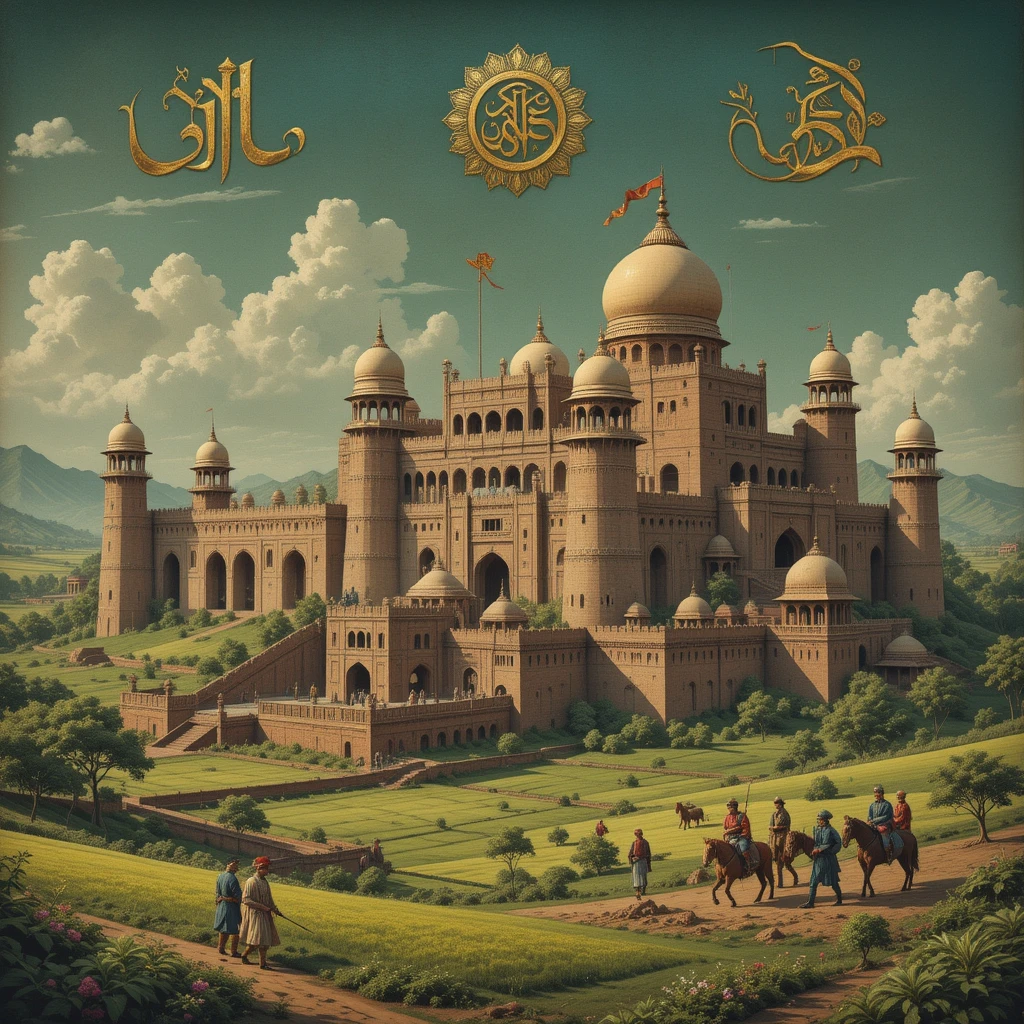

The Agra Fort, a majestic red sandstone citadel erected by Akbar in the 16th century and refined by Shah Jahan, represented Mughal splendor with its palaces, mosques, and vast treasuries. Controlling it meant dominating key trade corridors along the Yamuna and accessing immense wealth, which Surajmal leveraged to bolster his realm. His drive stemmed from a blend of tactical necessity—to secure borders near Bharatpur, about 50 kilometers away—and deeper historical animosities. The Jats harbored grudges against the Mughals dating back to the 1669 rebellion led by Gokula, who was executed near this very fort. Surajmal’s success in 1761 can be seen as a poetic retribution, avenging past oppressions while capitalizing on the chaos after the Third Battle of Panipat in January 1761, where Ahmad Shah Durrani’s Afghans decimated the Marathas, leaving a void for ambitious locals like the Jats.

Surajmal, often dubbed the “Plato of the Jats” for his wisdom or likened to Ulysses for his cunning, was born to Raja Badan Singh and Rani Devki in the Sinsinwar Jat lineage, tracing back to Sobha Singh of Bayana as the 21st descendant. From an early age, he exhibited leadership, aiding his father in forging a cohesive state from fragmented Jat groups. By his formal ascension in 1755, he had already proven his mettle in battles, transforming Bharatpur into a prosperous entity with revenues rivaling major powers. His rule emphasized agricultural reforms, religious tolerance—protecting Hindu and Muslim sites alike—and strategic alliances, embodying a vision of unified Indian resistance against foreign incursions.

This rewritten exploration revisits Surajmal’s saga, drawing from diverse historical accounts to ensure originality and depth. It delves into his formative years, the Jat kingdom’s evolution, precursor campaigns, the Agra siege’s intricacies, subsequent endeavors, lingering debates like monument desecration, his demise, and lasting heritage. By weaving in primary records such as the poetic “Sujan Charitra” by court bard Sudan, Persian chronicles like “Tarik-e-Ahmadshahi,” and inscriptions from sites like Deeg Palace and Kusum Sarovar, this narrative aims for authenticity. Modern interpretations from scholars like G.C. Dwivedi and K.R. Qanungo further enrich the analysis, highlighting Surajmal’s role in reshaping northern India’s power dynamics amid Mughal twilight.

In 2025, as Uttar Pradesh commemorates “Agra Vijay Diwas” on June 12—approved earlier this year—to honor the 1761 triumph, Surajmal’s story resonates anew, inspiring discussions on regional autonomy and cultural preservation in contemporary India.

Early Life and the Foundations of Leadership

Surajmal’s journey began in the modest environs of Bharatpur, where he was raised in a family steeped in Jat traditions of resilience and community solidarity. As the son of Badan Singh, who formalized the Jat state in the 1720s, Surajmal inherited a legacy of defiance against Mughal overreach. Badan Singh, titled “Raja” by the Mughals in 1724 as a placatory gesture, built key strongholds like Deeg and Kumher, laying infrastructural groundwork. Inscriptions at Deeg’s Purana Mahal, dating to this period, extol Badan Singh’s constructions, symbolizing the shift from nomadic raiding to settled governance.

From adolescence, Surajmal immersed himself in military affairs. By the 1730s, as de facto regent, he orchestrated conquests such as Mendu in 1730 and Farah, subduing local chieftains like the Bhadoria Rajputs near Agra. These early victories honed his skills in siege tactics and diplomacy, essential for later exploits. Historical manuscripts portray him as a pragmatic ruler who prioritized farmer welfare—Jats being primarily agriculturists—implementing revenue systems inspired by Mughal models but adapted for equity. His annual revenues soared to 175 lakhs by mid-century, funding armies and fortifications.

Surajmal’s personal ethos blended martial vigor with philosophical insight. He patronized arts, as evidenced by “Sujan Charitra,” which chronicles his life in verse, and fostered interfaith harmony, employing officials based on merit regardless of background. This inclusivity helped unite disparate Hindu and Muslim factions, envisioning a cohesive “Indian nation” amid fragmentation. His court attracted poets and scholars, reflecting a Renaissance-like atmosphere in Bharatpur.

Comparatively, Surajmal paralleled contemporaries like the Maratha Peshwas in ambition but differed in his localized focus on Doab consolidation rather than pan-Indian expansion. Unlike the opportunistic Rohillas, he emphasized sustainable rule, remitting transit duties to boost trade and constructing markets in Deeg to attract merchants. These policies not only enriched his treasury—estimated at 9 to 20 crores in cash plus jewels—but also fostered economic stability in an era of anarchy.

The Evolution of the Jat Kingdom

The Jats’ ascent traces to late 17th-century uprisings against Aurangzeb’s harsh policies, epitomized by Gokula’s 1669 revolt, crushed brutally near Agra Fort. This fueled enduring resentment, positioning Jats as symbols of anti-Mughal resistance. Under Churaman (d. 1721), they operated as raiders, but Badan Singh (r. 1722–1755) institutionalized the kingdom, erecting forts and securing nominal Mughal legitimacy.

Jat society, rooted in egalitarian clans like Sinsinwar, emphasized communal land ownership and warrior ethos. Surajmal built on this, expanding territories to encompass Agra, Alwar, Meerut, and beyond—over 20 modern districts. Primary sources like “Memoires des Jats,” compiled from Persian texts, depict this growth as a blend of coercion and alliance-building. Inscriptions at Vair and Kumher forts commemorate these expansions, highlighting architectural prowess with features like moats and bastions.

Economically, the kingdom thrived on fertile Doab lands, with Surajmal’s reforms making grain affordable and commerce vibrant. Politically, he navigated alliances astutely, as seen in his support for Safdar Jang against Mughals, leading to the 1753 Delhi plunder—celebrated as “Delhi Vijay Diwas” today.

The Panipat defeat in 1761 provided the catalyst for Agra’s capture, as Durrani’s withdrawal exposed Mughal vulnerabilities. Surajmal, having sheltered Maratha refugees post-battle, positioned himself as a stabilizing force.

Pre-1761 Campaigns: Forging a Warrior’s Path

Surajmal’s pre-Agra exploits laid the groundwork for his success. The 1745 Chandaus War saw him aid Nawab Fateh Ali Khan against Mughal forces, resulting in Asad Khan’s defeat and Bharatpur’s enhanced stature.

In 1748’s Battle of Bagru, he backed Jaipur’s Ishwari Singh with 10,000 troops against Madho Singh’s coalition, securing victory and Jaipur’s gratitude.

The 1753 Delhi incursion, allied with Safdar Jang, sacked key areas, humiliating the Mughals and extending Jat sway to Feroz Shah Kotla.

Kumher’s 1754 defense against Maratha siege ended with Khanderao Holkar’s death, forging a treaty that proved pivotal.

Alwar’s 1756 capture from Jaipur further solidified his domain. These campaigns amassed an army of 75,000 infantry and 38,000 cavalry, per contemporary estimates.

Prelude to the Agra Assault: Strategy and Opportunity

Post-Panipat, Surajmal eyed Agra for its strategic and economic value. The Mughal garrison, led by Mirza Fazilka Khan, was demoralized. Assembling 4,000-5,000 troops under Balram Singh and Imad-ul-Mulk, Surajmal planned meticulously from Mathura.

Motivations included border security, wealth acquisition, and symbolic revenge. “Tarik-e-Ahmadshahi” contextualizes this amid Afghan-Mughal strife.

The Encirclement and Victory: Step-by-Step Account

The operation launched May 3, 1761, with Jats approaching under camping pretext. Resistance sparked clashes near Jama Masjid, claiming 200 lives. Surajmal reinforced on May 24, seizing Koil and Jalesar.

Tactics involved family arrests for leverage and bombardment. A Rs. 1 lakh bribe plus villages sealed surrender on June 12.

“Sujan Charitra” vividly narrates the drama, corroborated by French compilations.

Post-Victory Measures: Consolidation and Growth

Surajmal integrated Agra, appointing administrators and harnessing revenues. In 1762, sons Jawahar and Nahar expanded into Haryana, conquering Farrukhnagar and Rohtak, envisioning a Jat alliance against Rohillas.

He negotiated with foes, supporting Ghazi-ud-din, while fortifying defenses like Lohagarh, deemed impregnable.

Debates and Allegations: Monument Treatment

Claims of Taj Mahal desecration—silver doors melted, structure stuffed with hay—surface, but evidence points to Jawahar Singh in 1763-1764, post-Surajmal. Accounts suggest Surajmal halted excesses, preserving sites per his tolerant ethos. Biased Mughal records inflated these, but modern analyses clarify his non-involvement.

Final Days and Enduring Influence

Surajmal met his end on December 25, 1763, ambushed by Rohillas near Hindon despite superior forces. His cenotaph at Kusum Sarovar, adorned with Krishna and battle scenes, honors him.

Legacy includes universities like Maharaja Surajmal Brij University and metro stations. In 2025, Agra Vijay Diwas revives his memory, influencing debates on Hindu resurgence and regional identity.

Sources and References

Primary:

- “Sujan Charitra” by Sudan (Bharatpur manuscripts).

- “Memoires des Jats” (Persian-based French text).

- “Tarik-e-Ahmadshahi” (Afghan-Mughal chronicle).

- Inscriptions: Deeg Palace, Kusum Sarovar cenotaph.

Secondary:

- Dwivedi, G.C. (1989). The Jats: Their Role in the Mughal Empire.

- Qanungo, K.R. (2003). History of the Jats.

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1950). Fall of the Mughal Empire, Vol. 2.

- Maheshwari, Anil (1996). Taj Mahal: Moon Still Shines.

- Bhatia, O.P. Singh (1968). History of India, 1707-1856.

- Havell, E.B. (1913). A Handbook to Agra and the Taj.