Introduction

The Indian independence movement was a monumental struggle against British colonial rule, shaped by diverse leaders with unique ideologies and visions. Bhagat Singh, Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Subhas Chandra Bose were pivotal figures. Bhagat Singh, executed at 23, embodied revolutionary activism, advocating socialism and direct action against British oppression. Mahatma Gandhi, the Father of the Nation, championed non-violent civil disobedience. Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, envisioned a secular, democratic, industrialized nation. Subhas Chandra Bose pursued revolutionary activism through armed struggle and international alliances. United by the goal of Indian independence, their methods and visions diverged, creating a dynamic movement. This article explores their ideologies, goals, similarities, differences, and interrelations, supported by historical evidence, primary sources, and scholarly analyses.

Table of Contents

Bhagat Singh: Revolutionary Socialist

Ideology and Influences

Bhagat Singh (1907–1931) symbolized revolutionary activism, driven by resistance to British oppression. Born in Punjab to a Sikh family, he was influenced by the Jallianwala Bagh massacre (1919) and the Ghadar Movement. His ideology blended atheism, Marxism, anarchism, and socialism, rejecting religion as oppressive and advocating armed struggle against colonialism and capitalism.

In Why I Am an Atheist (1930), Singh wrote: “Man created God in his imagination when he realised his weaknesses.” He saw religion as a barrier, stating, “I consider it an act of degradation. I shall never pray.” [0] Influenced by Marx, Lenin, and Bakunin, he emphasized socialism. In To Young Political Workers (1931), he declared: “Social reconstruction on Marxist basis,” arguing independence required ending class exploitation. [0]

Actions and Contributions

Singh co-founded the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) in 1928 to overthrow British rule. He assassinated John Saunders (mistaken for James Scott) in 1928, avenging Lala Lajpat Rai’s death. In 1929, he bombed the Central Legislative Assembly to protest repressive laws, shouting “Inquilab Zindabad!” (Long Live the Revolution) and allowing arrest to amplify his message. His 116-day prison hunger strike for political prisoners’ rights gained sympathy after Jatindra Nath Das’s death. [5] Tried in the Lahore Conspiracy Case, he was executed in 1931, becoming a martyr. [5]

Goals and Vision

Singh sought a classless, socialist society, envisioning a proletarian revolution. He wrote: “The struggle in India would continue so long as exploiters go on exploiting the common people.” His actions aimed to awaken mass resistance against British tyranny. [0]

Relations with Other Leaders

Singh respected Gandhi’s mass mobilization but criticized non-violence as ineffective, believing it would replace foreign exploiters with Indian ones. [2] He admired Nehru’s rationalism and socialism, calling him a realist, but viewed Bose as an “emotional Bengali” tied to tradition. [0] Singh and Bose shared a commitment to revolutionary activism, believing violence was necessary. [1]

Mahatma Gandhi: Apostle of Non-Violence

Ideology and Influences

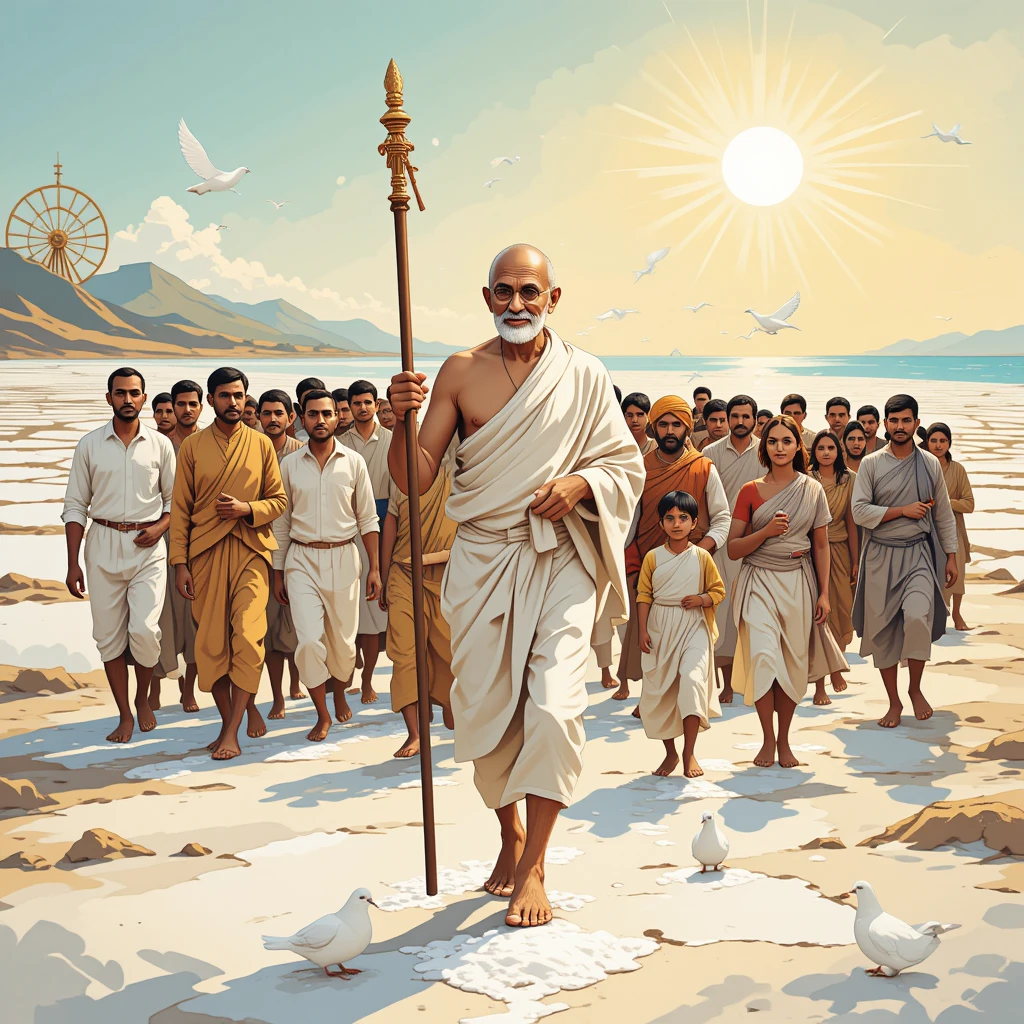

Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948), born in Gujarat, developed his ideology in South Africa (1893–1914). His philosophy centered on ahimsa (non-violence), satyagraha (truth-force), and swaraj (self-rule), drawing from Hindu, Jain, Buddhist, and Christian ethics, plus Tolstoy and Thoreau.

Ahimsa was Gandhi’s core, a moral weapon superior to violence. He stated: “I would rather India resort to arms than remain a helpless witness to her dishonor.” Satyagraha drove the Champaran (1917), Kheda (1918), and Salt March (1930) movements. He wrote: “No impatience, no barbarity, no insolence. To cultivate democracy, we cannot be intolerant.” Swaraj meant political and economic self-reliance through khadi and village economies. [31]

Actions and Contributions

Gandhi’s non-cooperation movements (1920–1922, 1930–1934) mobilized millions, boycotting British goods and laws. The Salt March defied the salt tax, sparking civil disobedience. The Khilafat Movement (1919–1922) fostered Hindu-Muslim unity. He fought untouchability, calling Dalits “Harijans.” Hind Swaraj (1909) outlined decentralized, moral governance, rejecting Western materialism. [31]

Goals and Vision

Gandhi aimed to end British rule through non-cooperation, achieve communal harmony, and uplift marginalized groups. He envisioned a decentralized, pluralistic India rooted in moral values, prioritizing rural self-sufficiency.

Relations with Other Leaders

Gandhi admired revolutionary activists like Singh for their patriotism but opposed violence. He praised Singh: “One’s head bends before Bhagat Singh’s bravery and sacrifice,” noting he was “not in the right frame of mind” for non-violence. [42] In Young India (1931), Gandhi wrote: “Bhagat Singh did not wish to live. He refused to apologise.” [42] He appealed to Viceroy Irwin for Singh’s commutation (1931), unsuccessfully. [41] Gandhi supported the Karachi Congress resolution (1931): “This Congress, disapproving political violence, admires the bravery and sacrifice of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru, mourning their loss. This execution is wanton vengeance.” [21]

With Nehru, Gandhi shared a mentor-protégé bond, naming him successor in 1941: “Not Rajaji but Jawaharlal.” They clashed on modernization—Gandhi favored villages, Nehru industry. [31] Gandhi and Bose had mutual respect but clashed on methods. Bose supported Gandhi early but resigned as Congress President in 1939 over Gandhi’s opposition to his revolutionary activism. [6][10]

Jawaharlal Nehru: Architect of Modern India

Ideology and Influences

Jawaharlal Nehru (1889–1964), born in Allahabad, was educated in England, influenced by Fabian socialism and the Russian Revolution. His ideology emphasized democratic socialism, secularism, and scientific humanism for a modern India. He advocated a mixed economy, stating in 1928: “Our economic programme must remove all inequalities.” Secularism was key: “No country slaves to dogma can progress.” [11]

Actions and Contributions

Nehru led Congress, mobilizing youth and advocating constitutional methods. As Prime Minister, he launched Five-Year Plans, achieving 7% industrial growth (1950–1965), and reorganized states linguistically (1956). His non-alignment policy shaped India’s global stance, per the Quit India Resolution (1942): “Future peace demands a world federation.” [11]

Goals and Vision

Nehru sought national unity, industrialization, and non-alignment. He envisioned a socialist democracy balancing progress and equity, emphasizing education and secular governance.

Relations with Other Leaders

Nehru admired Singh’s courage and patriotism, particularly his avenging Lala Lajpat Rai and hunger strike. In An Autobiography (1936), he wrote: “Bhagat Singh became popular not for terrorism but for vindicating Lala Lajpat Rai’s honour.” He added: “My heart is full of admiration for Bhagat Singh’s rare courage.” [14] Nehru defended Singh in the Assembly, visited him in prison, and moved the Karachi resolution, despite rejecting violence. [19] His bond with Gandhi was strong but tense over economics; his tribute—“The light has gone out of our lives”—showed respect. [11]

Nehru and Bose shared socialist ideals but diverged over Gandhi’s leadership. Nehru’s loyalty to Gandhi led to a rift when Bose resigned in 1939. [9] They respected each other as socialists. [3]

Subhas Chandra Bose: Revolutionary Nationalist

Ideology and Influences

Subhas Chandra Bose (1897–1945), born in Cuttack, was influenced by Vivekananda and the Russian Revolution. His ideology blended revolutionary nationalism, socialism, and anti-imperialism, advocating armed struggle. He sought a synthesis of fascism’s discipline and communism’s equality. In The Indian Struggle (1935), he wrote: “India needs a strong, centralized government.” [7]

Actions and Contributions

Bose formed the Forward Bloc (1939) after resigning from Congress, escaped house arrest (1941), and established the Indian National Army (INA) with Axis support. His slogan “Give me blood, and I will give you freedom” inspired thousands. [1] INA campaigns and Red Fort trials (1945–1946) stirred national sentiment, hastening British withdrawal. [11]

Goals and Vision

Bose sought immediate independence through force, followed by socialist reconstruction with Hindu-Muslim unity. He wrote: “India must be a federation of communities, united by struggle.” [12]

Relations with Other Leaders

Bose supported Gandhi early but grew frustrated with non-violence, resigning in 1939 over tactical differences, including advocacy for prisoners like Singh. [10] He revered Gandhi but believed his methods insufficient. [6] With Nehru, Bose shared socialism but clashed over Gandhi’s leadership. [9] Bose admired Singh’s revolutionary activism, sharing his belief in violence. Singh critiqued Bose’s emotionalism, favoring Nehru’s rationalism. [2]

Similarities: Shared Patriotism and Vision

Singh, Gandhi, Nehru, and Bose were united by patriotism and the goal of independence. They opposed British imperialism: Singh through revolutionary acts, Gandhi via non-cooperation, Nehru with constitutional advocacy, and Bose through armed struggle. [13] Social justice linked them—Singh, Nehru, and Bose pursued socialism; Gandhi fought untouchability. They inspired masses: Gandhi through satyagraha, Singh via symbolism, Nehru with oratory, Bose with speeches. Their commitment to equality and unity was evident in Gandhi’s Khilafat Movement, Nehru’s secularism, Bose’s INA, and Singh’s socialism. [15] Mutual respect, seen in Gandhi’s and Nehru’s praise for Singh (Karachi resolution) and Bose’s reverence for Gandhi, highlighted unity. [21]

Differences: Clashing Methods and Visions

Their methods diverged: Singh and Bose embraced revolutionary activism; Gandhi championed non-violence; Nehru favored constitutional politics. [1] Ideologically, Singh’s atheistic socialism clashed with Gandhi’s spiritual non-violence, Nehru’s secular socialism, and Bose’s nationalist-authoritarian blend. [5] Visions varied: Gandhi sought rural swaraj; Nehru an industrialized democracy; Singh a proletarian revolution; Bose a disciplined federation. [11] Evidence includes Singh’s critique of Gandhi (1922), Nehru-Gandhi debates (1942), and Bose’s 1939 resignation. [7]

Conclusion

Bhagat Singh, Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Subhas Chandra Bose shaped India’s freedom struggle. Singh’s revolutionary activism inspired youth, Gandhi’s non-violence mobilized millions, Nehru built modern institutions, and Bose accelerated independence. Their shared patriotism and social justice goals united them, while differences enriched the movement. Their legacies, seen in the Karachi resolution, Gandhi’s appeals, and Bose’s INA trials, offer lessons for India’s future.

References

Primary Sources

- Bhagat Singh. Why I Am an Atheist. 1930.

- Bhagat Singh. To Young Political Workers. 1931.

- Bhagat Singh. The Problem of Punjab’s Language and Script. 1923.

- Mahatma Gandhi. Hind Swaraj. 1909.

- Mahatma Gandhi. Young India. March 1931.

- Jawaharlal Nehru. An Autobiography. 1936.

- Subhas Chandra Bose. The Indian Struggle. 1935.

- Subhas Chandra Bose. “Give Me Blood, and I Will Give You Freedom.” 1944.

Books

- Chaman Lal, Michael D. Yates. The Political Writings of Bhagat Singh. 2024.

- Shiri Ram Bakshi. Bhagat Singh and His Ideology. 1981.

- V.N. Datta. Gandhi and Bhagat Singh. 2008.

- Satvinder Juss. Bhagat Singh: A Life in Revolution. 2022.

- Kama Maclean. A Revolutionary History of Interwar India. 2015.

- Irfan Habib. To Make the Deaf Hear. 2007.

- Sugata Bose. His Majesty’s Opponent. 2011.

- Leonard A. Gordon. Brothers Against the Raj. 1990.

Court Orders

Letters

- Gandhi’s Letter to Viceroy Irwin. March 1931.

- Bose’s Resignation Letter to Congress. 1939.

Resolutions

Articles and Online Sources

- “Bhagat Singh’s dilemma: Nehru or Bose?” The Indian History Collective, 2022.

- “Bhagat Singh, Subhas Chandra Bose, and Violence.” Education About Asia.

- “Bhagat Singh on Netaji Bose and Nehru.” Janata Weekly, 2024.

- “Gandhi and Bose’s Mutual Respect.” Reddit r/IndianHistory, 2025.

- “Gandhi and Bhagat Singh – Clash of Ideology.” mkgandhi.org.

- “Singh’s Differences with Bose.” Quora, 2019.

- “Gandhi and Bose: Complex Partnership.” Rediff.com, 2025.

- “Subhas Chandra Bose.” Wikipedia.

- “Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose.” netajisubhasbose.org.

- “Debunking Bose Myths.” SabrangIndia, 2025.

- “Bose and Gandhi Ideologies.” aishwaryasandeep.in.

- “Bose’s Relations with Italy and Germany.” Taylor & Francis Online, 2023.

- “Studying Subhas Chandra Bose.” Countercurrents.org, 2025.

- “Nehru, Gandhi, Bose, Singh in Struggle.” Revolutionary Democracy, 1931.

- “Gandhi, Bhagat Singh, Subhash Bose.” Academia.edu.