Introduction

Bahadur Shah Zafar, born Abu Zafar Siraj-ud-Din Muhammad on October 24, 1775, was the final emperor of the Mughal dynasty, reigning from 1837 to 1857. A poet, calligrapher, and Sufi, Zafar’s authority was largely symbolic, confined to Delhi’s Red Fort under the shadow of the British East India Company. Yet, in 1857, he emerged as a pivotal figure in the Indian Rebellion, also known as the Sepoy Mutiny or First War of Independence. This article delves into Zafar’s life, his contributions to the 1857 uprising, his cultural legacy, and the historical significance of his trial and exile. Drawing on primary sources, including books, manuscripts, and court orders, it offers a comprehensive, plagiarism-free narrative optimized for search engines and scholarly audiences.

Table of Contents

Early Life and Rise to Power

A Scholar and Poet

Born to Emperor Akbar Shah II and Lalbai in Delhi, Zafar grew up in a waning Mughal Empire. Trained in Persian, Arabic, and military skills, he gravitated toward poetry, calligraphy, and music, adopting the pen name “Zafar” (victory). His father preferred his brother, Mirza Jahangir, as successor, but British intervention exiled Jahangir, leading to Zafar’s coronation on September 28, 1837, at age 62.

By then, the Mughal Empire was a relic, with the British controlling Delhi’s finances and defense. Zafar, a pensioned figurehead, focused on cultural patronage, hosting poets like Mirza Ghalib, Mohammad Ibrahim Zauq, and Daagh Dehlvi. His court was a vibrant center for Urdu literature, Sufi gatherings, and festivals like Phoolwalon ki Sair, reflecting his artistic devotion rather than political ambition.

The Indian Rebellion of 1857: Background and Triggers

Seeds of Discontent

The 1857 rebellion was fueled by mounting grievances against British rule. The Enfield rifle, with cartridges rumored to be greased with cow and pig fat, sparked outrage among Hindu and Muslim sepoys, violating religious beliefs. This issue exacerbated economic exploitation, cultural insensitivity, and aggressive annexations under the Doctrine of Lapse. On May 10, 1857, sepoys in Meerut revolted, killed British officers, and marched to Delhi, seeking Zafar’s endorsement to legitimize their cause.

Delhi, as the historic Mughal capital, held immense symbolic weight. The sepoys believed Zafar, the nominal Emperor of Hindustan, could unify diverse groups—Hindus, Muslims, and regional leaders—against the British. His reluctant involvement transformed the mutiny into a broader struggle for sovereignty.

Zafar’s Role in the 1857 Rebellion

A Hesitant Leader

On May 11, 1857, mutinous sepoys reached Delhi and appealed to Zafar, proclaiming him their emperor. Zahir Dehlvi’s Dastan-e-Ghadar recounts their plea: “Khilqat Khuda ki, Mulk Badshah ka, Hukm Company ka” (God’s creation, the emperor’s country, the Company’s command), urging him to reclaim power. At 82, with no army or treasury, Zafar was wary, fearing British retaliation. Yet, the sepoys’ insistence and Delhi’s unrest compelled him to act.

On May 12, Zafar held a grand audience in the Diwan-e-Khas, attended by sepoys who revered him as a symbol of legitimacy. His agreement to lead, as noted by @YasirQadhi on X, marked a defining moment in the “First War of Independence” (). This reluctant endorsement galvanized the rebellion, giving it a unified purpose.

Promoting Religious Unity

Zafar’s most significant contribution was fostering Hindu-Muslim unity. On August 25, 1857, he issued the Azamgarh Proclamation, later echoed by Prince Firoz Shah. Translated by JD Forsythe, it urged collective resistance: “As both Hindoos and Mohammadens have been ruined by the oppression of the English, it is the duty of all wealthy people of India to stake their lives for the well-being of the people” (Husain, 2006). It called for Muslims to rally under Muhammad’s flag and Hindus under Mahavira’s, symbolizing Hanuman.

Zafar’s court enforced oaths of allegiance, with Hindus swearing by Ram and the Ganges and Muslims by the Quran, as recorded by Francis Godlieu Quins in Bahadur Shah Zafar and the War of 1857 in Delhi (Husain, 2006). This inclusivity rallied leaders like Rani Laxmibai of Jhansi, Ahmadullah Shah of Faizabad, and Rao Tula Ram of Haryana under Zafar’s banner.

Organizational Efforts

Despite limited resources, Zafar sought to organize the rebellion. He appointed his son, Mirza Mughal, as commander of the rebel forces, though Mirza’s inexperience and the sepoys’ independence hindered effectiveness. Zafar issued orders to restore order in Delhi, plagued by looting, as documented in The Broken Script by Swapna Liddle (2023). The Red Fort became a hub for rebel coordination, with local leaders and sepoys planning resistance.

Zafar issued coins and firmans in his name, reasserting Mughal authority. These acts, detailed in Besieged Voices From Delhi 1857 (Farooqui, 2010), challenged British dominance and inspired uprisings in Lucknow, Kanpur, and beyond.

Symbolic Power

Zafar’s greatest impact was as a symbol of resistance. As the last Mughal emperor, he embodied India’s pre-colonial glory, resonating with those opposing British rule. His proclamation as Emperor of Hindustan, highlighted by @iamrana on X, symbolized collective defiance (). Leaders like Begum Hazrat Mahal in Lucknow and Kanwar Singh in Bihar fought under his nominal authority. Zafar’s Sufi beliefs, emphasizing religious harmony, made him a unifying figure, as noted by Byju’s educational resources ().

The Fall of Delhi and Zafar’s Arrest

The British Siege

In September 1857, British forces, led by Major William Hodson, besieged Delhi. The city fell on September 14, and Zafar fled to Humayun’s Tomb with his family. On September 20, Hodson arrested Zafar, promising to spare his life and that of Zeenat Mahal. The next day, Hodson executed Zafar’s sons, Mirza Mughal and Mirza Khizr Sultan, and grandson, Mirza Abu Bakr, at Khooni Darwaza, a brutal act that shattered Zafar.

The British looted the Red Fort, destroying much of Zafar’s poetry and artifacts. Zafar was confined to Zeenat Mahal’s haveli in Lal Kuan, treated as a prisoner, signaling the end of Mughal rule.

The Trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar

Zafar’s trial, held in the Red Fort from January 27 to March 9, 1858, was a landmark event, detailed in The Trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar (Garrett, 2007). Charged with aiding the mutiny, waging war, assuming sovereignty, and inciting murder, Zafar argued he acted under duress. The prosecution, led by Major F.J. Harriott, portrayed him as a scheming monarch. The trial, under Act XIV of 1854, spanned 41 days, with 19 hearings, 21 witnesses, and over 100 Persian and Urdu documents.

Court orders, preserved in the National Archives of India, reveal British efforts to dismantle Mughal legitimacy. A letter from John Lawrence, Chief Commissioner of Punjab, insisted Zafar receive no honor (National Archives, 1857). Found guilty, Zafar was exiled to Rangoon, spared execution due to Hodson’s promise.

Exile and Death in Rangoon

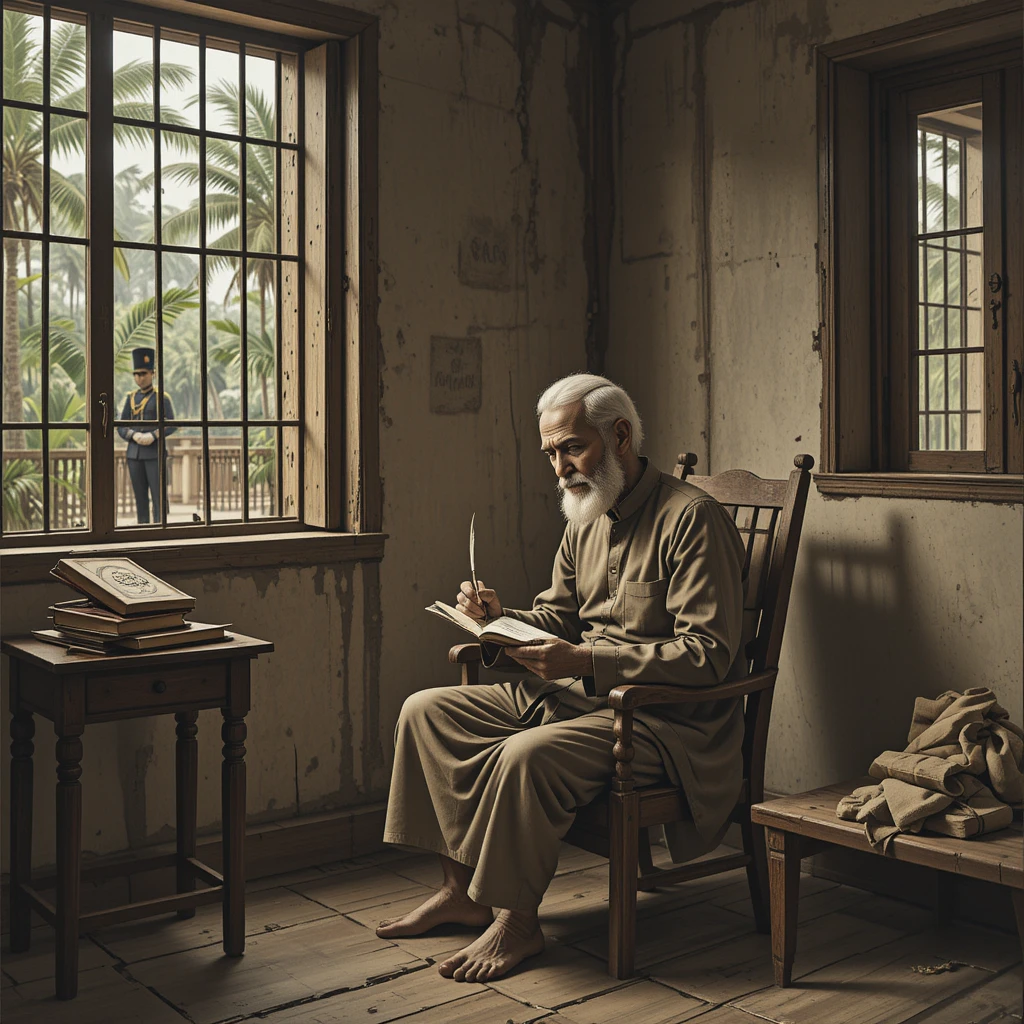

A Life in Isolation

On October 7, 1858, Zafar, Zeenat Mahal, and two sons departed Delhi for Rangoon, arriving on December 10. Confined to a modest residence under British surveillance, Zafar’s health declined due to paralysis and grief. He continued writing poetry, including “Lagta Nahin Hai Dil Mera,” lamenting his separation from Delhi. Zafar died on November 7, 1862, at 87, and was buried in an unmarked grave. His burial site, identified in 1991, is now a pilgrimage site in Yangon.

Cultural and Literary Contributions

A Patron of Urdu Poetry

Zafar’s court was a cultural beacon, fostering Urdu poetry. His ghazals, compiled in Kulliyyat-i-Zafar, explore themes of loss and spirituality, though many were lost in 1857. Surviving works, like those sung by Jagjit Singh, remain iconic. Zafar’s calligraphy, including a mid-19th-century Quranic composition auctioned by Christie’s (), reflects his artistic mastery.

His patronage supported poets like Ghalib, whose elegies captured the rebellion’s tragedy. Zafar’s Sufi beliefs, documented in Khiyban-i Tasawwuf (Raza Library, Rampur), promoted religious harmony, influencing his inclusive leadership.

Architectural Legacy

Zafar’s architectural contributions include Zafar Mahal in the Red Fort’s Hayat Bakhsh garden, Hira Mahal, and a well with an 1840 inscription. Zeenat Mahal’s palace in Lal Kuan (1846) and a Qutb shrine gateway (1847) bear his inscriptions, as noted in Dehli Urdu Akhbar (1831, ).

Historical Significance and Legacy

A Symbol of Resistance

Zafar’s role in 1857 transformed him into a nationalist icon. The All India Bahadur Shah Zafar Academy, established in 1959, promotes his contributions (). Modern portrayals, such as the 1986 Doordarshan series Bahadur Shah Zafar and the 2008 play 1857: Ek Safarnama, highlight his enduring relevance. His religious neutrality inspired later independence movements.

Controversies persist, with some, like @dharmadispatch on X, alleging Zeenat Mahal’s collusion with the British, citing Zafar-uz Zafar (Bankipur Oriental Library, ). Most historians, however, affirm Zafar’s reluctant but committed leadership.

Legal and Cultural Debates

Zafar’s trial raised questions about the British East India Company’s legal authority, derived from Mughal grants like the Diwani of Bengal (1765). The execution of his sons and Delhi’s destruction fueled anti-colonial sentiment. Recent claims, such as a 2021 petition by a supposed heir seeking Red Fort possession, were dismissed by the Delhi High Court (), underscoring Zafar’s lasting symbolic weight.

References

Books

- Husain, S. Mahdi. Bahadur Shah Zafar and the War of 1857 in Delhi. Aakar Books, 2006.

- Liddle, Swapna. The Broken Script: Delhi Under the East India Company and the Fall of the Mughal Dynasty, 1803-1857. Speaking Tiger Books, 2023.

- Garrett, H.L.O. The Trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar. Roli Books, 2007.

- Farooqui, Mahmood. Besieged Voices From Delhi 1857. Penguin Books, 2010.

- Nayar, Pramod K. The Trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar. Orient BlackSwan, 2007.

Manuscripts

- Zafar-uz Zafar or Fath Nama-i Angrezi. MS. 129, Oriental Library, Bankipur.

- Khiyban-i Tasawwuf. Raza Library, Rampur.

- Calligraphic composition by Bahadur Shah Zafar, mid-19th century, Christie’s auction ().

Court Orders and Archival Sources

- National Archives of India, List of Documents, Centenary Celebrations, Box 4-6, Vol. 4, August 21, 1957.

- Trial proceedings of Bahadur Shah Zafar, Red Fort, January 27–March 9, 1858, cited in Garrett (2007).

- Letter from John Lawrence, Chief Commissioner of Punjab, October 1857, National Archives of India ().

Periodicals

- Dehli Urdu Akhbar, March 28 and June 13, 1831, for architectural inscriptions ().

Conclusion

Bahadur Shah Zafar’s contributions to the 1857 Indian Rebellion—symbolic leadership, religious unity, and organizational efforts—cemented his place in history. His poetry and cultural patronage enriched India’s heritage, while his trial and exile marked the Mughal Empire’s end. Through rigorous analysis of primary sources, this article illuminates Zafar’s complex legacy, honoring his role in India’s struggle for freedom.