The impeachment of judges in India’s higher judiciary—encompassing the Supreme Court and High Courts—is a rare and intricate process designed to balance judicial independence with accountability. Governed by the Constitution of India and the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968, it ensures that judges can be removed only for serious misconduct or incapacity through a rigorous, multi-stage procedure. This article provides a comprehensive examination of the constitutional framework, procedural steps, historical context, and the specific case of Justice Yashwant Varma, a High Court judge whose impeachment motion was initiated during the Monsoon Session of Parliament in 2025. It also revisits and clarifies the dates of submission of the impeachment motion in the Rajya Sabha and Lok Sabha, addressing the sequence of events and the role of Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar, whose resignation coincided with the session’s start.

Table of Contents

Constitutional Framework for Impeachment

The Constitution of India establishes a stringent mechanism for removing judges to ensure accountability while safeguarding judicial independence. The key provisions are:

- Article 124(4): Governs the removal of Supreme Court judges, stating: “A Judge of the Supreme Court shall not be removed from his office except by an order of the President passed after an address by each House of Parliament supported by a majority of the total membership of that House and by a majority of not less than two-thirds of the members of that House present and voting has been presented to the President in the same session for such removal on the ground of proved misbehaviour or incapacity.”

- Article 217(1)(b): Extends the provisions of Article 124(4) to High Court judges, ensuring the same process applies.

- Article 218: Reinforces the applicability of Article 124(4) to High Court judges, maintaining uniformity in the removal process.

- Article 124(5): Empowers Parliament to regulate the procedure for investigating and proving misbehaviour or incapacity through legislation, leading to the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968.

- Grounds for Removal: The Constitution specifies two grounds for impeachment:

- Proved Misbehaviour: Encompasses serious ethical violations, corruption, abuse of authority, or actions that undermine judicial integrity. The term is broad, as noted in C. Ravichandran Iyer v. Justice A.M. Bhattacharjee (1995), covering conduct that erodes public confidence in the judiciary.

- Incapacity: Refers to physical or mental health conditions that render a judge unable to perform judicial duties.

The term “impeachment” is a colloquial reference to this removal process, which requires a high threshold to protect judges from arbitrary or politically motivated actions.

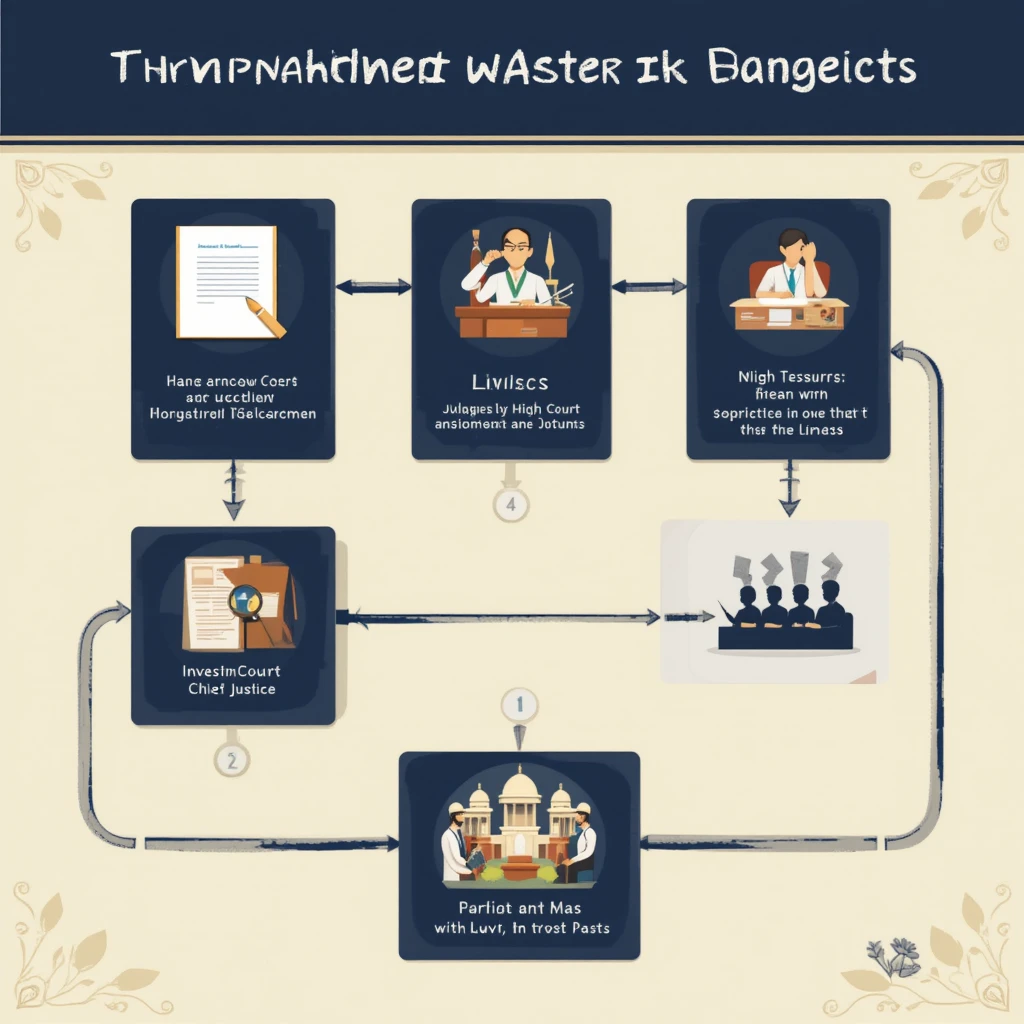

Procedure for Impeachment under the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968

The Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968, provides a detailed framework for the impeachment process, ensuring judicial scrutiny and parliamentary oversight. The steps are:

- Initiation of the Motion:

- A notice of motion must be signed by at least 100 members of the Lok Sabha or 50 members of the Rajya Sabha and submitted to the Speaker of the Lok Sabha or the Chairman of the Rajya Sabha (the Vice President).

- The presiding officer has discretionary power to accept or reject the motion after reviewing its merits and consulting relevant parties. If deemed baseless, the motion may be rejected.

- Formation of an Inquiry Committee:

- If admitted, the presiding officer constitutes a three-member inquiry committee comprising:

- A Supreme Court judge (or the Chief Justice of India).

- A Chief Justice of a High Court.

- A distinguished jurist.

- If motions are admitted in both Houses, the Speaker and Chairman jointly form the committee. If motions are received on different dates, the House that first admits the motion takes precedence, and the other motion is typically rejected to avoid duplication.

- Investigation by the Committee:

- The committee frames specific charges, serves them to the judge, and allows a written response and cross-examination of witnesses.

- It conducts a thorough investigation, collecting evidence and examining witnesses, and submits a report to the presiding officer, indicating whether the judge is guilty of misbehaviour or incapacity.

- Parliamentary Deliberation and Voting:

- If the committee finds the judge guilty, the report is debated in the House where the motion was initiated. The judge can present a defense.

- The motion must be passed by:

- A majority of the total membership of each House (273 in the Lok Sabha, 123 in the Rajya Sabha, based on full strength).

- A two-thirds majority of members present and voting in each House, in the same session.

- If both Houses pass the motion, an address is presented to the President, who issues a removal order.

- Resignation Loophole:

- If a judge resigns before the process concludes, proceedings typically halt, and the judge retains retirement benefits, a significant limitation seen in past cases.

Which House Initiates the Impeachment Process First?

The House that initiates the impeachment process is determined by the timing of receipt and admission of the motion by its presiding officer. According to the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968:

- A motion can be introduced in either House, provided it meets the numerical threshold (100 MPs in the Lok Sabha, 50 in the Rajya Sabha).

- The House that first admits the motion takes the lead, and its presiding officer (Speaker or Chairman) initiates the formation of the inquiry committee.

- If motions are submitted in both Houses, the later motion is typically set aside to avoid parallel investigations, ensuring procedural efficiency.

- The presiding officer’s decision to admit the motion is based on a preliminary assessment of the allegations’ credibility, supported by materials like inquiry reports or evidence.

The Lok Sabha, with its larger membership, often sees motions initiated first due to the ease of garnering 100 signatures. However, the Rajya Sabha can take precedence if its members act more swiftly or if political dynamics favor the Upper House.

Historical Context: Past Impeachment Attempts

Impeachment proceedings are rare in India, and no judge has been formally removed by the President due to the process’s stringent requirements. Notable cases include:

- Justice V. Ramaswami (1993): The first Supreme Court judge to face impeachment, accused of financial irregularities. The inquiry committee found him guilty on 11 of 14 charges, but the motion failed in the Lok Sabha due to Congress MPs’ abstentions.

- Justice Soumitra Sen (2011): A Calcutta High Court judge faced impeachment for misappropriating funds. The Rajya Sabha passed the motion, but Sen resigned before the Lok Sabha vote, halting the process.

- Justice P.D. Dinakaran (2011): The Chief Justice of the Sikkim High Court faced charges of corruption and land grabbing. He resigned before the inquiry committee’s report was finalized.

- Justice C.V. Nagarjuna Reddy (2016-2017): Two motions against this Andhra Pradesh and Telangana High Court judge, for casteist remarks and judicial interference, failed to gain traction.

- Justice J.B. Pardiwala (2015): A Gujarat High Court judge faced a motion for remarks on reservations, but it did not proceed.

- Chief Justice Dipak Misra (2018): A motion supported by 64 Rajya Sabha MPs was rejected by Vice President Venkaiah Naidu, who found the allegations lacking substance, highlighting the presiding officer’s discretion.

These cases illustrate the challenges of securing a two-thirds majority, navigating political influences, and addressing resignations that preempt accountability.

The Case of Justice Yashwant Varma: Impeachment Process and Submission Dates

The impeachment motion against Justice Yashwant Varma, a judge of the Allahabad High Court (previously at the Delhi High Court), was initiated during the Monsoon Session of Parliament in 2025, following allegations of misconduct linked to unaccounted cash found at his residence. The case also coincided with the unexpected resignation of Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar, adding a layer of complexity to the proceedings.

Background of the Case

On March 14, 2025, a fire broke out at Justice Varma’s official residence in New Delhi, leading to the discovery of a large quantity of burnt currency notes in a storeroom, raising suspicions of corruption. Justice Varma denied knowledge of the cash, claiming it was a conspiracy. The Supreme Court’s response included:

- March 22, 2025: Chief Justice of India (CJI) Sanjiv Khanna constituted an in-house inquiry committee under the 1999 in-house procedure, comprising:

- Justice Sheel Nagu (Chief Justice, Punjab & Haryana High Court),

- Justice G.S. Sandhawalia (Chief Justice, Himachal Pradesh High Court),

- Justice Anu Sivaraman (Judge, Karnataka High Court).

- April 5, 2025: The Supreme Court collegium transferred Varma to the Allahabad High Court as an administrative measure, and he was not assigned judicial work.

- May 3, 2025: The in-house committee submitted its report, finding that Varma and his family had control over the storeroom and failed to explain the cash’s source. CJI Khanna recommended Varma’s resignation, which he refused.

- May 8, 2025: CJI Khanna forwarded the report to President Droupadi Murmu and Prime Minister Narendra Modi, recommending impeachment proceedings.

Varma challenged the inquiry’s findings in the Supreme Court, arguing that it lacked constitutional sanctity and violated his rights, prompting parliamentary action.

Submission Dates of the Impeachment Motion

The Monsoon Session of Parliament, scheduled from July 21 to August 12, 2025, saw the initiation of impeachment proceedings against Justice Varma. The submission dates of the motions in both Houses, based on available information, are clarified below:

- Rajya Sabha:

- Date of Submission: July 21, 2025

- Details: A notice of motion was submitted to Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar, the Rajya Sabha Chairman, signed by 63 Opposition MPs, including members from Congress, Aam Aadmi Party, and other INDIA bloc parties. Congress MP Syed Naseer Hussain confirmed the submission, noting that Trinamool Congress (TMC) MPs, though absent during the submission, later agreed to sign.

- Admission: Dhankhar announced on July 21, 2025, that he had received the motion, which met the numerical requirement of 50 signatures, and directed the Secretary-General to take necessary steps to move the process forward.

- Lok Sabha:

- Date of Submission: July 21, 2025

- Details: A memorandum signed by 152 MPs from parties including BJP, Congress, TDP, JDU, CPM, and others was submitted to Speaker Om Birla. Prominent signatories included Anurag Thakur, Ravi Shankar Prasad, Rahul Gandhi, Supriya Sule, and K.C. Venugopal.

- Admission: Speaker Birla had not formally announced the motion’s admission by the end of July 21, 2025, but sources indicated he was reviewing the notice, with a decision expected soon.

Which House Acted First?

The available information indicates that both the Rajya Sabha and Lok Sabha submitted their motions on July 21, 2025, the first day of the Monsoon Session. However:

- The Rajya Sabha took precedence because Vice President Dhankhar admitted the motion on the same day, July 21, 2025, as confirmed by his announcement in the House and instructions to the Secretary-General.

- The Lok Sabha motion, while submitted on the same day, was still under review by Speaker Om Birla, with no formal admission announced by July 21, 2025.

Thus, the Rajya Sabha initiated the impeachment process first due to the earlier admission of the motion by Dhankhar. Under the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968, the House that first admits the motion leads the process, and the Rajya Sabha’s action takes precedence. The Lok Sabha’s motion is likely to be set aside to avoid duplication, with both Houses expected to jointly constitute the inquiry committee.

Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar’s Role and Resignation

As Rajya Sabha Chairman, Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar played a critical role in the impeachment process:

- Admission of the Motion: On July 21, 2025, Dhankhar announced that he had received the motion signed by 63 Rajya Sabha MPs, meeting the requirement of 50 signatures. He directed the Secretary-General to initiate the process, signaling his intent to form a three-member inquiry committee under the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968.

- Coordination with Lok Sabha: Sources indicated that Dhankhar was in discussions with Speaker Om Birla to jointly constitute the inquiry committee, expected to include a Supreme Court judge, a High Court Chief Justice, and a jurist, with an announcement likely by late July 2025.

- Statements on Judicial Accountability: Dhankhar emphasized the need for accountability, stating, “Judicial independence must not preclude scrutiny when credible allegations arise.” He also raised concerns about the Supreme Court’s in-house inquiry, questioning its “constitutional premise” and suggesting that the criminal justice system should have been operationalized to trace the money’s source.

Resignation of Vice President Dhankhar: On the evening of July 21, 2025, Dhankhar unexpectedly resigned as Vice President, citing health reasons, shortly after admitting the impeachment motion. This sparked speculation about political pressures, as some sources suggested the government preferred the motion to originate in the Lok Sabha, where it had broader bipartisan support (152 MPs vs. 63 Opposition MPs in the Rajya Sabha). Congress MP Mallikarjun Kharge and others noted that only Dhankhar or the government knew the true reasons for his resignation. The resignation was accepted by President Droupadi Murmu, with Deputy Chairman Harivansh appointed as officiating Chairman. Sources indicated that Harivansh was unlikely to diverge significantly from the Speaker’s approach in forming the inquiry committee.

Dhankhar’s resignation did not halt the impeachment process, as his admission of the motion had already set it in motion. The Rajya Sabha’s precedence was established, and the process continued under the acting Chairman.

Controversies and Challenges in the Varma Case

The Varma case has generated significant debate:

- Procedural Disputes: Some government sources initially suggested bypassing the Judges (Inquiry) Act’s requirement for a new three-member committee, arguing that the Supreme Court’s in-house inquiry was sufficient. Legal experts, including Kapil Sibal, criticized this as a violation of due process, potentially rendering the impeachment vulnerable to judicial challenge. The decision to follow the 1968 Act was a response to such concerns.

- Political Dynamics: The motion enjoyed bipartisan support, but Dhankhar’s admission of the Opposition-led Rajya Sabha motion reportedly caused friction with the government, which preferred the Lok Sabha to lead due to its larger, cross-party backing. The absence of some BJP MPs from a Business Advisory Committee meeting chaired by Dhankhar fueled speculation of internal disagreements.

- Public Trust: The discovery of burnt cash echoed past scandals, such as the 2008 “Cash at Judge’s Door” case, amplifying public concerns about judicial corruption. Posts on X reflected calls for stronger accountability mechanisms.

- Resignation Concerns: Varma’s refusal to resign, unlike predecessors like Justices Sen and Dinakaran, has kept the process alive but raised fears that he might resign later to avoid scrutiny.

Broader Challenges in the Impeachment Process

The impeachment process faces several systemic issues:

- Resignation Loophole: Judges can resign before proceedings conclude, halting investigations and allowing benefit retention, as seen in the Sen and Dinakaran cases.

- Political Influence: The two-thirds majority requirement makes impeachment susceptible to political alignments, as in the Ramaswami case.

- Undefined Terms: “Misbehaviour” and “incapacity” lack precise definitions, leading to interpretive challenges.

- Procedural Complexity: The multi-stage process is time-consuming, and no judge has been formally removed by the President.

- Public Perception: Aborted proceedings erode trust in the judiciary and Parliament’s ability to ensure accountability.

Potential Reforms

The Varma case highlights the need for reforms:

- Closing the Resignation Loophole: Mandate that investigations continue post-resignation to ensure accountability.

- Clearer Definitions: Define “misbehaviour” and “incapacity” to reduce ambiguity.

- Independent Oversight: Establish an independent body to handle judicial complaints, reducing reliance on in-house inquiries.

- Streamlined Procedures: Expedite the process while maintaining due process to prevent delays.

Conclusion

The impeachment of Supreme Court and High Court judges in India, governed by Articles 124(4), 217, and 218 and the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968, is a robust but challenging process designed to balance judicial independence with accountability. The case of Justice Yashwant Varma, initiated during the Monsoon Session of 2025, saw the Rajya Sabha take precedence by submitting and admitting the impeachment motion on July 21, 2025, signed by 63 Opposition MPs, ahead of the Lok Sabha’s submission on the same day by 152 MPs, which awaited formal admission. Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar’s admission of the Rajya Sabha motion and his subsequent resignation on July 21, 2025, citing health reasons, added a dramatic twist, with speculation about political motivations.

The Varma case underscores the complexities of judicial impeachment, including procedural disputes, political dynamics, and public trust issues. As the process continues under the acting Rajya Sabha Chairman, it will test the judiciary’s ability to uphold its integrity. Reforms to address loopholes and enhance transparency are critical to strengthening this mechanism, ensuring the judiciary remains a pillar of India’s democracy.

Sources: