Raja Ravi Varma (1848–1906) occupies a unique place in the history of modern Indian art. He is simultaneously celebrated as a technical master who absorbed European academic realism and surrealized it through Indian subjects, and criticized as an agent of commercialisation who transformed sacred images into widely distributed consumer objects. But to reduce him to a stereotype is to miss the complexity of his achievement: Varma was an innovator who used new technologies, entrepreneurial methods, and an instinct for visual narrative to reshape the way Indians saw gods, epics, and themselves. This essay traces his life, artistic practice, industrial venture (the lithographic press), the controversies and court interventions surrounding reproduction of his works, and the long shadow his images cast over popular devotional and visual culture in South Asia.

Table of Contents

Early Life and Formation: A Royal Talent

Raja Ravi Varma was born on 29 April 1848 in Kilimanoor, in the princely state of Travancore (present-day Kerala). He belonged to a matrilineal aristocratic family that had long-standing ties to the Travancore royal household. From an early age Varma displayed an aptitude for drawing and painting, a talent that was noticed and encouraged by local patrons and the Travancore administrative elite. His early training was eclectic: he learned watercolor techniques locally and received informal instruction from itinerant painters and British portraitists when opportunities arose. By the 1860s and 1870s his work had matured enough to win official patronage, prizes, and the public’s attention. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Style and Subject: Fusing European Realism with Indian Narrative

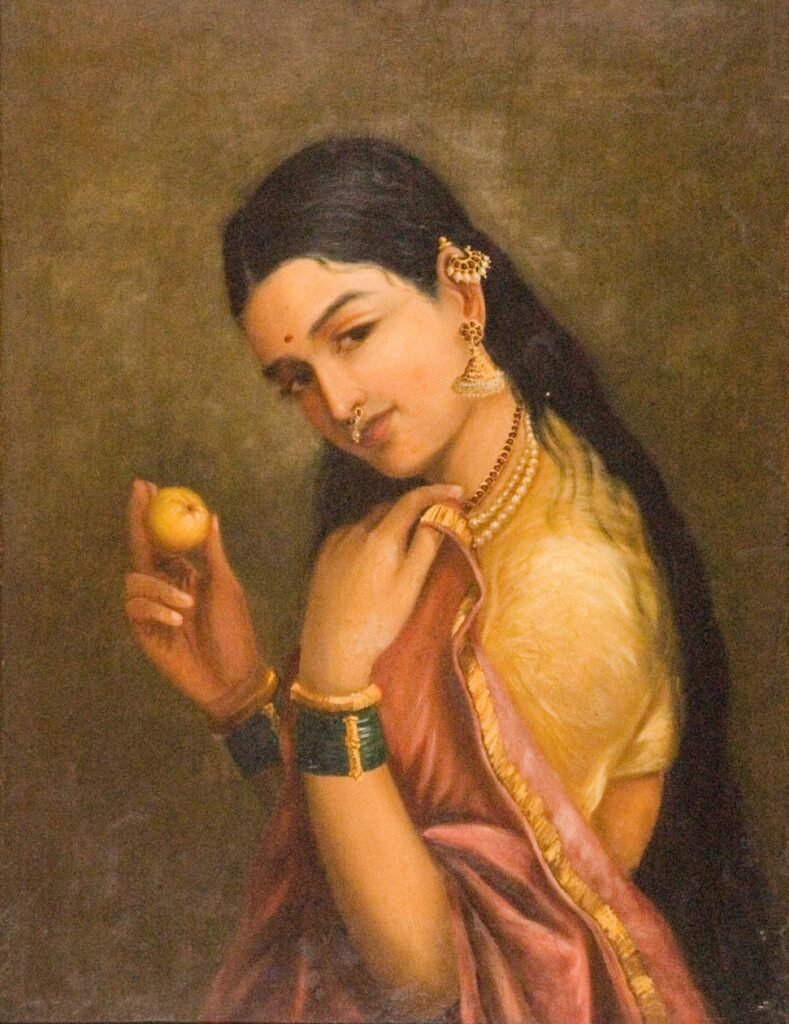

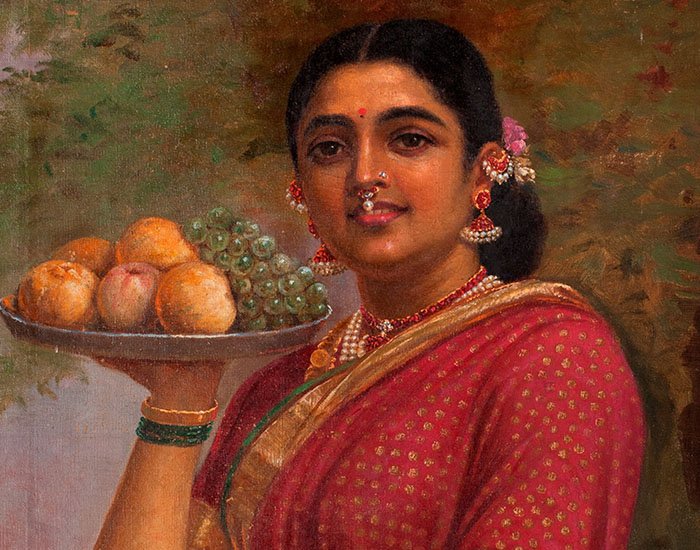

Ravi Varma’s pictorial language is notable for its elegant blending of Western methods with indigenous iconography. Where European academic painters used oil and a modeled form to suggest three-dimensional presence, Varma applied those methods to episodes from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, the Puranas, and classical Sanskrit drama. His compositions combined narrative clarity (a single event emphasized by clean lighting and focused gestures) with a careful attention to costume, ornament, and physiognomy that made characters feel culturally rooted. Paintings like Shakuntala, Nala and Damayanti, and many portraits of women show his capacity to capture emotional states—longing, repose, contemplation—through subtle manipulations of posture, gaze, and hand gesture. (Wikipedia)

It is important to note that Varma did not simply copy Western models. He adapted academic devices—studio lighting, foreshortening, naturalistic anatomy—so that they served Indian storytelling. His heroines wear Indian drapery; his gods bear classical attributes; the backgrounds often echo Indian motifs. This synthesis helped create a visual idiom intelligible to newly emergent publics—colonial administrators, Indian princes, middle-class literate audiences, and rural devotees.

Demonstrating a New Public: Portraits, Patronage, and Exhibitions

Varma’s early career allied him with princely patronage and colonial institutions. He was commissioned to paint portraits of rulers, princes, and dignitaries, and these works demonstrated his command of likeness and dignified presentation. But he also sought and obtained recognition beyond courtly circles: his paintings were sent to exhibitions in India and Europe, and he found critical success. For instance, his work won awards at exhibitions such as Vienna’s and the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition (1893), exposing him to an international art world and enhancing his stature at home. (Wikipedia)

Two things are critical here. First, Varma was an ambitious self-promoter who understood modern institutions of recognition—prizes, salons, and press. Second, these honors helped legitimize a novel artistic agenda in colonial India: oil painting and large-scale narrative pictures could be Indian in content while cosmopolitan in technique. This cosmopolitan legitimacy would later help Varma’s images travel far beyond elite salons.

The Press that Changed Devotion: Ravi Varma’s Lithographic Enterprise

Perhaps Varma’s most consequential decision was to make cheap, mass-produced reproductions of his paintings. In 1894, he established the Ravi Varma Fine Arts Lithographic Press in Bombay (Mumbai). The press produced oleographs and chromolithographs—highly colored prints that reproduced his oil paintings with remarkable fidelity. Because they were affordable, durable, and visually striking, these images quickly spread across households, temples, and shops. The press has been described as, for a time, “the largest picture printing establishment in India,” and its output transformed visual culture by putting polished pictorial images into the hands of ordinary people. (MAP Academy)

This mass production was revolutionary for two linked reasons. First, for devotional life: Hindu deities, once primarily experienced through temple sculpture, oral description, and ritual, were now visible in domestic shrines in the specific physiognomy and posture fashioned by Varma. The press popularized particular visual types—Rama’s benign gaze, Sita’s demure posture, Krishna’s playful smile—so thoroughly that some of them became the default mental images of those deities for generations. Second, for popular aesthetics: Varma’s domestic scenes, portraits of women, and mythological tableaux became models for calendar art, advertising, and theatrical set design.

Democratization, Devotion, and Critique: The Double-Edged Legacy

The social effects of Ravi Varma’s lithographs were profound and contested. On one hand, his images democratized access to high-quality art and gave ordinary people a way to “own” refined images of gods and epic scenes. Middle-class homes could now display these works, and religious festivals often featured his prints. On the other hand, critics—both contemporaneous and later—argued that mass production vulgarized sacred art. Some accused Varma of commercializing the sacred; others criticized his adoption of European aesthetics as a betrayal of indigenous styles. Academic critics debated whether his work diluted or enriched Indian visual culture.

These debates are important because they reveal tensions in colonial India: between tradition and modernity, sacred form and commercial circulation, caste-based temple imagery and commodified iconography. Varma’s defenders stressed the pedagogic and integrative potential of his images—how they familiarized broad publics with stories and moral exemplars—while his critics feared the flattening effect of repetition and market logic.

Legal Battles and the Question of Artistic Rights

When we speak of bringing gods to the masses, we must also speak of the institutions that made and policed the circulation of images. Varma’s creation of a press led to complex issues concerning reproduction rights, ownership, and the legal recognition of artistic property. During Varma’s lifetime and afterward, the proliferation of reproductions—both authorized and unauthorized—led to disputes that intersected with the nascent law of copyright in colonial India.

Legal recognition of copyright in visual art was still emerging in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in British India. Courts confronted questions about whether artists could control reproductions of their work, whether mechanical reproductions infringed on moral rights, and how commercial printers could be restrained. Some judgments and legal commentary from the period indicate that colonial courts recognized artists’ proprietary interests in their creations and could intervene against unauthorized reproduction; later legal texts and case notes specifically discussed disputes concerning reproductions of artworks and acknowledged that an artist (or his assignees) had valid rights over such works. These early legal engagements helped establish precedents that would influence how Indian courts thought about creative rights. (IJLHM)

A few points are worth emphasizing:

- Emergent Copyright Law: Copyright as a formal doctrine was developing in India along lines inherited from British law. The courts had to reconcile statutory language with the realities of mass reproduction in a colonial market.

- Enforcement Challenges: Even when courts recognized artists’ rights, enforcement against small printers and wide unauthorized circulation was difficult, especially in a subcontinent where print networks were extensive and informal.

- Afterlife and Public Domain: Over time, many of Varma’s original works passed into the public domain (either through expiration of term or ambiguous transmission of rights), and recreations, reinterpretations, and photographic adaptations proliferated. Contemporary disputes over creative appropriation of Varma’s images often hinge on whether particular reproductions are materially derivative of a protected expression or merely inspired by a public-domain composition. (ralegal.co.in)

Because the historical record on specific litigation involving Varma is scattered and often summarized in secondary accounts, scholars caution against making hyper-specific claims about named cases without archival corroboration. Still, the broader legal trajectory is clear: Varma’s mass reproductions created legal challenges that early colonial courts had to address, and those responses helped shape modern Indian jurisprudence on artistic reproduction.

Controversies, Scandals, and the Travancore Context

Raja Ravi Varma’s life was not free of controversies. Several of his portraits and mythological paintings occasioned local scandals and critical backlash in his native region and beyond. For instance, paintings that portrayed aristocratic women or royalty in intimate or modernized poses sometimes startled conservative observers. One episode often discussed concerns a portrait known in some accounts as Mahaprabha, a depiction associated with a member of the Travancore elite; some contemporary commentary treated the painting as socially transgressive in its frankness. Scholars have used such episodes to show how Varma’s aesthetic modernity could conflict with local codes of propriety.

It’s also worth noting that Varma’s relationship with traditional Hindu institutions was ambivalent. While many temples and devotees embraced his imagery, others resisted a popularized picture-ritual that substituted mass-produced images for locally meaningful sculptural forms and ritual contexts. These tensions reflect a broader cultural negotiation: how much of devotion is transferable into the market? Varma’s career exemplifies the possibilities and perils of such transfer.

Varma as Industrialist: Ambition, Strain, and Decline

Ravi Varma was not simply an artist; he was an entrepreneur. Running a lithographic press required capital, technical expertise, and managerial attention. Varma imported machinery, employed technicians (including some European or German specialists), and attempted to control production quality. Yet the press also curtailed the time he could spend painting original canvases. Many historians note that the industrial demands—long hours, the stress of managing a large operation, and the commercial pressures of meeting market tastes—took a toll on his creativity and finances.

Indeed, by the early 20th century his press experienced losses and practical difficulties; moreover, the market for reproductions changed as other printers and local imitators entered the field. Varma’s declining health (he died in 1906) and the complicated succession of his estate meant that the business did not remain a dominant cultural force under his direct supervision. Nonetheless, the artefacts—thousands of lithographs, calendars, and prints—remained in circulation, imprinting his visual lexicon across households and ritual contexts. (Google Arts & Culture)

The Visual Grammar of Devotion: How Varma’s Gods Became Everybody’s Gods

Why did Ravi Varma’s images have such staying power? Several factors combined:

- Visual Clarity and Emotional Tone: Varma’s compositions were narratively clear; facial expressions, gestures, and costume communicated readily recognizable moods and roles.

- Technical Quality: The chromolithographs reproduced subtle gradations of tone and color, producing a near-oil-painting effect that markedly improved on earlier woodcuts and hand-drawn prints.

- Affordability and Distribution: The printing technologies he used enabled low per-unit costs. Wide distribution to shops, temples, and itinerant vendors meant that his images reached cities and villages.

- Cultural Resonance: By choosing epic and devotional subjects, Varma’s work resonated with a cultural grammar already familiar to audiences. His images functioned as mnemonic devices for stories, and later as visual aids in educational, ritual, and theatrical contexts.

These features explain why Varma’s deities became, for many, the canonical visual types. For countless devotees, the face of Lakshmi or the posture of Krishna in a Ravi Varma print became as valid and recognizable as older sculptural representations. The consequence was a profound—if contested—democratization of sacred imagery.

Influence on Popular Art: Calendar Art, Cinema, and Advertising

The lineage of Varma’s visual idiom can be traced into multiple industries that define modern visual culture in India. Calendar art—cheap devotional or decorative images mass-produced for wall calendars—often borrows directly from Varma’s compositions or style. Early Indian cinema used his staging and lighting as templates for framing mythological sequences and song picturizations. Advertisements and commercial art, too, make visible debt to Varma’s techniques of glamour and sentiment.

Because Varma created a reproducible canon—specific compositions that could be printed and rearranged—later visual entrepreneurs had a ready set of images to use, adapt, and commodify. The moral ambivalence that greeted this commercialization in Varma’s day persists: mass visual economies amplify access but also flatten diversity.

Later Reappraisals: From Villain to Pioneer

Throughout the 20th century, assessment of Ravi Varma shifted. Early modernist critics often dismissed him as a mere academic painter beholden to colonial taste; nationalist critics sometimes condemned his Westernized techniques as betrayals of authentic Indian forms. Yet by the late 20th and early 21st centuries scholars and curators began reassessing his contribution, recognizing his technical mastery, narrative imagination, and political significance.

Contemporary exhibitions and art histories increasingly situate Varma in the context of cultural translation: his paintings were tools of cultural pedagogy that helped new publics imagine a visual India in the age of print. Museums such as India’s National Gallery of Modern Art and platforms like Google Arts & Culture have featured curatorial narratives that explore his hybrid aesthetics and social impact. The reassessment is not uncritical—but it recognizes Varma’s singular role in shaping modern South Asian visuality. (Wikipedia)

Court Cases and the Legal Afterlife: Rights, Reproductions, and Modern Disputes

As noted earlier, Varma’s mass reproduction raised legal questions. Historical sources indicate that colonial courts did address the reproducibility of artistic works and recognized protective interests in artistic creations, including judgments that touch on unauthorized reproduction of prints. The precise docket entries and comprehensive archival record for every dispute remain a subject for legal historians, but secondary legal studies identify Bombay High Court and other colonial tribunals as loci where the concept of copyright for paintings was affirmed in principle. These rulings helped seed the jurisprudential framework that would later govern Indian copyright law. (IJLHM)

In modern times, disputes have resurfaced about whether contemporary artists or companies can appropriate Varma’s imagery for commercial or artistic projects. Many of Varma’s originals are now in the public domain (given expired terms), but disputes sometimes arise when a modern reproduction closely copies a particular lithograph or when a descendant or an institution claims rights over a particular print run or plate. Legal commentary suggests that, where the author’s economic rights have expired, protection may still be sought via trademark, moral-rights claims, or contractual restrictions tied to specific reproductions sold by rights-holders. The practical upshot is that Varma’s case continues to be a touchstone for debates about cultural heritage, ownership, and the commercialization of devotional imagery. (ralegal.co.in)

Ethical and Cultural Questions: Appropriation, Agency, and Representation

The story of Ravi Varma forces us to ask enduring questions about art in the public sphere. Is it a betrayal for an artist to popularize sacred images? Does the artist have an ethical obligation to control how images of gods are used? When reproductions circulate, who benefits economically and culturally—the artist, his heirs, the temple economy, or commercial middlemen?

Some critics see Varma as complicit in the commodification of devotion; others see him as democratizing access to art and instruction in epic narratives. Both perspectives are useful. Varma’s images functioned as pedagogy: for many Sanskrit-illiterate households, a Ravi Varma print conveyed a millennium of mythic narrative at a glance. But his images were also easy material for commercial exploitation, and the rise of cheap devotional prints meant that artists and printers beyond Varma could—and did—appropriately reproduce sacred forms in ways that removed them from ritual contexts.

The Global Turn: Collections, Exhibitions, and Scholarship

Today Raja Ravi Varma is represented in prestigious collections and featured in international exhibitions. Major Indian museums, private collectors, and international galleries preserve and display his oils and lithographs. Scholarly interest has expanded: historians of art and visual culture study Varma’s techniques, his press, and the social effects of his pictorial economy. Recent digital projects, exhibitions, and catalogues explore his repertoire with new archival work, high-resolution reproductions, and interdisciplinary approaches that situate him at the intersection of art history, legal history, and cultural studies. (Google Arts & Culture)

Conclusion: A Complicated Canon

Raja Ravi Varma remains a figure of paradox: a royal artist who popularized images of the gods; a technical traditionalist who embraced industrial reproduction; a cultural modernizer many saw as westernizing and others hailed as integrating. What is undeniable is the magnitude of his impact. By making finely rendered images widely available, Varma helped shape not just how people in his lifetime visualized epic narratives and divinities, but how subsequent generations would recognize and relate to them.

His life opens a window onto questions that remain urgent today: how visual culture forms collective memory, how technology transforms religious experience, and how legal institutions mediate the claims of artists, markets, and publics. Courts in colonial India wrestled with the new legal problems that mass reproduction posed, and those early interventions prefigured modern debates about copyright, cultural property, and the public domain. The prints that once hung in humble household shrines now also hang in museums—reminders that the same image can be devotional, commercial, controversial, and canonical all at once.

Select Bibliography and Further Reading

- “Ravi Varma.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. (biographical and stylistic overview). (Encyclopedia Britannica)

- “Wanderers Between Worlds: Story Of The Ravi Varma Press.” Google Arts & Culture / The Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation (on the press and its social impact). (Google Arts & Culture)

- “Raja Ravi Varma Press.” MAP Academy (history of the lithographic press and distribution). (MAP Academy)

- Thakurta, T. G. “The Case of Raja Ravi Varma (1848-1906).” [Journal article] (historical sketch and reproduction issues). (SAGE Journals)

- Legal commentary on reproduction and copyright in colonial India (discussions that reference cases recognizing artistic rights). (IJLHM)