Paul-Henri Thiry, Baron d’Holbach (1723–1789), emerges as one of the most uncompromising and influential radicals of the French Enlightenment. His works represent the pinnacle of 18th-century materialist philosophy, boldly advancing atheism, determinism, and a secular ethic grounded in human happiness and reason. Born in Germany and thriving in Paris through inherited wealth, d’Holbach transformed his home into a legendary salon that nurtured radical ideas. His anonymous publications evaded censorship while challenging the foundations of religion, monarchy, and traditional metaphysics.

Table of Contents

This extensively expanded article explores d’Holbach’s biography, intellectual milieu, and major works in depth. Particular emphasis falls on his core doctrines—materialism, determinism, atheism, and ethics/politics—as articulated across his corpus, especially in Système de la nature (1770) and subsequent treatises.

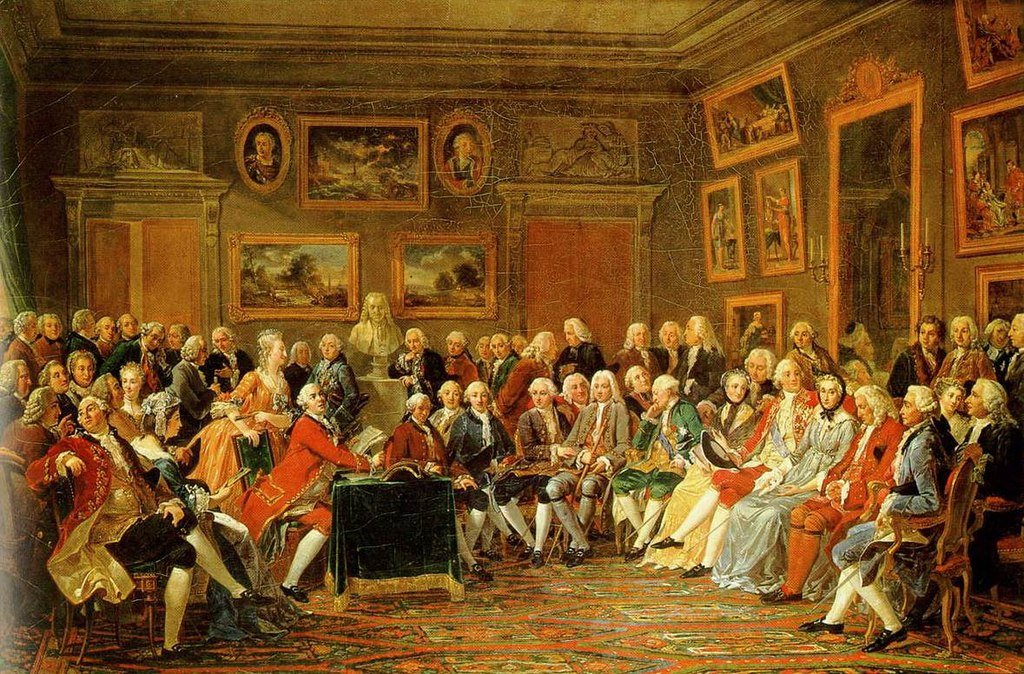

Portraits of Paul-Henri Thiry, Baron d’Holbach, depicting the enlightened patron and philosopher whose ideas shook the foundations of 18th-century thought.

Biography and Intellectual Formation

Early Life and Education

Paul Heinrich Dietrich was born on December 8, 1723, in Edesheim, Palatinate (Holy Roman Empire). Orphaned young, he was raised by his uncle François-Adam d’Holbach, a wealthy financier who naturalized him in France and bestowed the baronial title. Educated in Paris and likely at Leiden University—a bastion of empirical and freethinking scholarship—d’Holbach absorbed Newtonian physics, Lockean empiricism, and Hobbesian materialism. These influences shaped his rejection of Cartesian dualism and metaphysical speculation.

By the 1740s, he translated German scientific works on chemistry and geology, honing a commitment to empirical observation over abstract theology.

Life in Paris and Personal Circumstances

Settling permanently in Paris, d’Holbach married twice (his first wife died in 1754; he remarried her cousin). He fathered four children and lived comfortably on rue Royale (now rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré). His fortune funded lavish dinners and publications, insulating him from the perils faced by less privileged radicals.

D’Holbach contributed over 400 articles to Diderot’s Encyclopédie, primarily on metallurgy, chemistry, and mineralogy, while subtly infusing materialist undertones. He died on January 21, 1789, months before the French Revolution his ideas indirectly fueled.

The Coterie Holbachique: Epicenter of Radical Enlightenment

Structure and Participants

D’Holbach’s salon, active from the 1750s to the 1780s, hosted twice-weekly gatherings attracting Europe’s intellectual elite. Core members included Denis Diderot (intimate friend and possible collaborator), Claude-Adrien Helvétius (utilitarian precursor), Abbé Raynal, Jacques-André Naigeon (d’Holbach’s literary executor), and occasional visitors like David Hume, Horace Walpole, Benjamin Franklin, and Cesare Beccaria.

The atmosphere encouraged unbridled discussion of taboo subjects: atheism, materialism, and political reform. Unlike Madame Geoffrin’s more moderate salon, d’Holbach’s fostered outright radicalism.

Illustrations and paintings evoking the vibrant intellectual exchanges in 18th-century French salons, central to the dissemination of Enlightenment radicalism.

Role in Shaping d’Holbach’s Philosophy

Debates refined his ideas; Diderot’s sensualism and Helvétius’s self-interest ethics echoed in his works. The salon disseminated clandestine manuscripts, amplifying materialist and atheistic arguments across Europe.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau attended early but later denounced the group as conspiratorial in his Confessions, highlighting tensions between sentimental deism and hardline atheism.

Core Philosophical Doctrines: Foundations of d’Holbach’s System

D’Holbach’s philosophy integrates into a cohesive naturalism, rejecting supernaturalism and dualism.

Materialism: The Ontological Basis

D’Holbach’s materialism asserts that matter in motion constitutes all reality. Nature is eternal, self-sufficient, and governed by immutable laws—no immaterial souls, spirits, or deities required.

In Système de la nature, he argues matter possesses inherent properties like gravitation and sensibility. Mind emerges from organized matter (brain); consciousness is a physical process. Influenced by Lucretius, Hobbes, and Locke, he extends empiricism to monism: “Everything in the universe is matter in motion.”

Critiques of idealism: Descartes’ dualism creates insoluble mind-body problems; Berkeley’s immaterialism denies experience. Materialism aligns with science, explaining phenomena without “occult qualities.”

Implications: No afterlife, no divine intervention—human life bounded by physical necessity.

Determinism: Necessity and Human Action

D’Holbach champions strict determinism: All events, including volitions, follow causal chains. Humans, as complex machines, act from motives determined by temperament, education, and environment.

Free will is illusory—a comforting fiction masking necessity. In Système, he writes: “Man is at every instant a passive instrument in the hands of necessity.”

This softens moral judgment: Vice stems from poor organization or circumstances, not “sin.” Education and laws can reform behavior. Critics (Voltaire) feared it undermined responsibility; d’Holbach counters that determinism encourages compassion and reform over punishment.

Atheism: Critique of Religion and Theism

D’Holbach’s atheism is uncompromising: Gods arise from ignorance, fear, and anthropomorphism. Religion perpetuates superstition, justifying tyranny.

Key arguments:

- No empirical evidence for God.

- Problem of evil contradicts benevolent deity.

- Historical religions evolve from primitive fears.

- Theology riddled with contradictions.

In early works like Christianisme dévoilé, he exposes Christianity’s pagan borrowings; in Système, religion as a tool of oppression: “If ignorance gave birth to gods, knowledge will destroy them.”

Atheism liberates humanity for rational morality.

Ethics and Politics: Utilitarian Naturalism

Ethics derive from nature: Happiness (self-preservation and pleasure) is the ultimate good. Virtue promotes mutual utility; vice harms society.

No divine commands needed—”common sense” suffices. Influenced by Helvétius, d’Holbach advocates enlightened self-interest: True happiness aligns personal and social welfare.

Politically, he supports social contract theory: Governments exist for collective happiness, enforcing justice and equality. Despotism and clericalism oppose this; reform toward enlightened rule, though he warns against anarchy.

In Système social and Politique naturelle, he outlines secular governance promoting education, tolerance, and welfare—prefiguring modern utilitarianism and secularism.

Conceptual illustrations representing Enlightenment debates on materialism, determinism, and atheism.

Major Works: Chronological and Thematic Analysis

Early Anti-Religious Polemics (1760s)

Works like Christianisme dévoilé (1761) and Théologie portative (1768) satirize religion, laying groundwork for atheism.

Système de la nature (1770): The Comprehensive Synthesis

This magnum opus integrates all doctrines.

*Rare first editions of *Système de la nature, the foundational text of modern atheism and materialism.

Detailed exposition:

- Part I: Materialist physics and cosmology.

- Part II: Deterministic psychology, atheistic critique, utilitarian ethics.

Later Ethical and Political Treatises (1770s–1780s)

Le Bon Sens (1772) popularizes ideas; Système social (1773) and Morale universelle (1776) elaborate secular politics and ethics.

Reception, Legacy, and Contemporary Relevance

Condemned in his time, d’Holbach influenced revolutionaries, positivists, Marxists, and modern atheists. His doctrines remain central to debates on free will, secular ethics, and naturalism.